An urban redevelopement

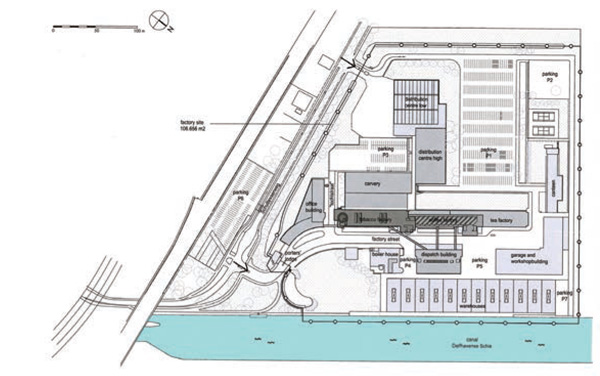

The Van Nelle Factory (Van Nellefabriek in Dutch) complex is located in the northwest of the city of Rotterdam in the industrial zone called Spaanse Polder. The total factory site measures a little over 10 hectares and is bordered by a canal, the Delfshavense Schie. The complex is on the Unesco World Heritage list and has a reinforced concrete factory street as well as a factory garden, former tobacco, coffee and tea factories, an office building and a dispatch building with garages and warehouses with a quay along the canal. The complex is practically in its original state and enjoys State Monument protection

Van Nelle and the world

The Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company) and the West-Indische Compagnie (Dutch West India Company) established overseas trading posts in the ‘East’ (Indonesia, Sri Lanka) and the ‘West’ (Brazil, Surinam, Antilles), facilitating a great number of raw materials and end products. The specific origin of the Van Nelle company dates from 1782, when Johannes van Nelle (1756-1811) started a shop selling coffee, tea, tobacco and snuff, in premises located on the edge of the old inner city of Rotterdam.

Kees van der Leeuw: The principal visionary

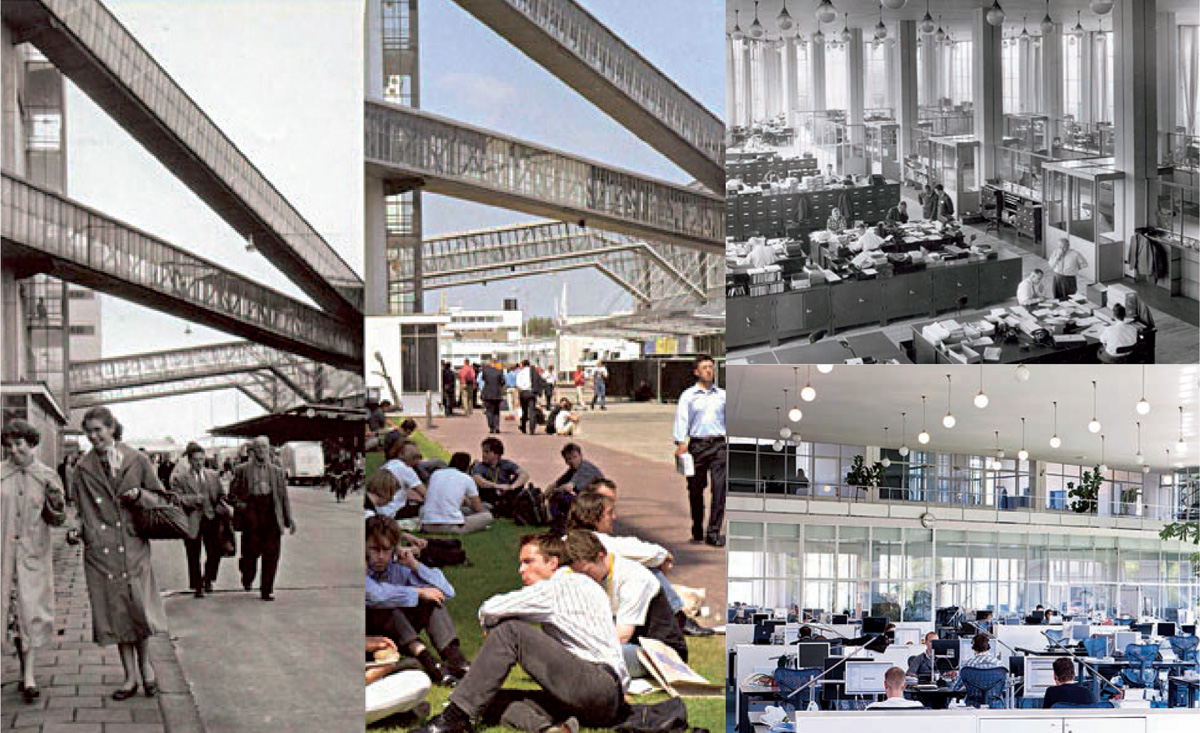

Since 1837, the Van der Leeuw family was involved with the Van Nelle company. This family was of crucial importance for the establishment of the first daylight factory in the Netherlands. Between 1925 and 1931, a brand-new industrial complex: The Van Nellefabriek was realized in the virtually undeveloped Spaanse Polder, in accordance with the most modern and enlightened ideas of that time.

The complex designed by the architects Brinkman and Van der Vlugt between 1925 and 1931 is practically in its original state | |

The factory was designed by famous Dutch architects, A Brinkman and LC van der Vlugt. Kees van der Leeuw was a practical idealist who sought to bring about a fundamental improvement of human labor conditions in factories by means of humanization and creating a good working environment. He utilized European and American examples and added new elements such as extra personnel facilities, clear visibility of the site from the main traffic arteries and efficient use of transport of raw materials. He had a great influence on the design and development of the factory complex, combining his theosophical orientation with inspiration gained in America and elsewhere.

The adaptive reuse of the Van Nellefabriek

In 1995, the owners decided to move their business activities elsewhere and sell the complex. However, they considered it a moral duty to transfer the cultural heritage of the monument in a responsible manner and to guarantee a good way of adaptive reuse and preservation. In 1999 Wessel de Jonge was appointed the coordinating architect for this mission.

The idea behind adaptive reuse is focused on the preservation of the architectural and functional integrity. One of the greatest challenges was to preserve the original clarity and transparency of the Van Nellefabriek. In the Master Plan, four forms of transparency are distinguished: the lines of vision across the site to the buildings, the view from the buildings, the vistas through the buildings and the view from outside of the interior’s front zone.

A box-in-a-box solution

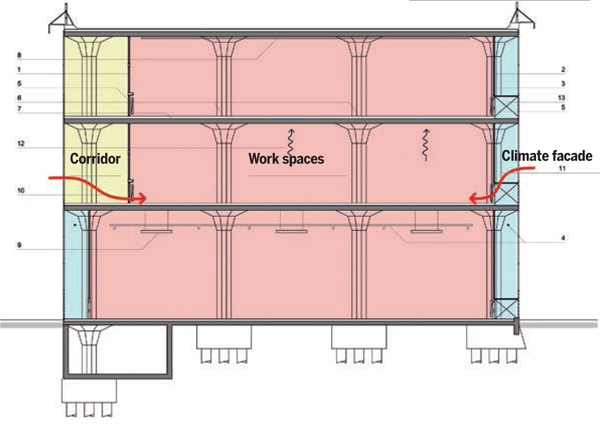

Within the authentic structure of the factories, a reversible infill was designed that guaranteed the required interior climate performance for the new use but which, like a ‘box’, was positioned almost entirely independent of the carefully preserved façades.

A double façade was used in which secondary glazing was placed behind the original façade. The intermediate zones thus formed create a buffer against external climatological influences and the noise from the nearby railway line and the highway.

On the north-eastern side, the secondary glazing was set well back, whereby the intermediate space serves as a corridor. On the southwest side, where the solar gain is much greater, the additional glazing follows the line of the original sun shades between the columns. This intermediate space of 80 cms acts as a sort of climate wall. The system for automatically opening the vertical pivot windows is based on a technique applied in greenhouse construction.

Photographs of the different work spaces as they are today. | |

Transformation into a design factory

Nowadays, the complex is used by a unique variety of tenants in the field of communication, design and architecture.

The powerful image of the Van Nellefabriek is a strong marketing tool, which supports their own company identity. In the creative sector the paradox is often found that while the tenants wish to identify with the collective image of Van Nelle, they also wish to stand out individually. Therefore, guidelines were drawn up for future furnishing, fittings, additional unit divisions, meeting rooms or acoustic improvements. Those were made part of the tenancy agreements and the municipal heritage bureau.

Emblem of modern culture

The iconic Van Nellefabriek is recognized worldwide as the purest embodiment of an internationally oriented metropolitan culture, aiming for the advancement of social and artistic progress and an open civil society. Through the streamlined design and the strong corporate identity, the site is a lasting emblem of modern culture and a continuous source of inspiration for contemporary works of art and design.

Photographs: Robert Aarts, Fas Keuzenkamp / Drawings: Wessel de Jonge Architecten

Comments (0)