Cities have to deal with major transformations, concerning not only population rates but also social redefinitions and spatial reconstructions. The major changes that technology brought were ease in movement, the advent of the automobile and its supporting infrastructure. The evolution of movement systems through air was also an offshoot of automobiles and its impact on our cities. The airplane has stitched the world together into a small spatial system through its web of intense speed. This visionary design has shown its dark side and the euphoria over it seems to be eroding because of its ill effects. We must thrive to generate a more sustainable form of movement.

Vincent Callebaut Architectures, in their project Hydrogenase, address the issue of movement patterns with sustainability, self- sufficient systems and recycling systems generating a very potent movement model conducive to our urban and natural environment.

HYDROGENASE ALGAE FARM TO RECYCLE CO2 FOR BIO-HYDROGEN AIRSHIP

Between engineering and biology, Hydrogenase is one of the projects of bio-mimicry, which draws its inspiration from the beauty and shapes of nature. Professor of Biomimetics, Julian Vincent defines bio-mimicry as “the abstraction of good design from nature” and “the conscious emulation of nature’s genius.” In Vincent Callebaut’s design, this inhabited vertical aircraft incorporates a clean and efficient mobility system to meet the needs of the population. It uses biofuels and sees itself as the ecosensitive transport of the future.

A MOVEMENT ELEMENT WITH MULTIPLE FLEXIBLE USES

Hydrogenase marks a new generation of state- of-the-art hybrid airships. It can function for humanitarian missions, rescue operations and airfreight and could also generate complementary activities like entertainment, eco-tourism, hotels, human transportation, air media coverage and territorial water surveillance.

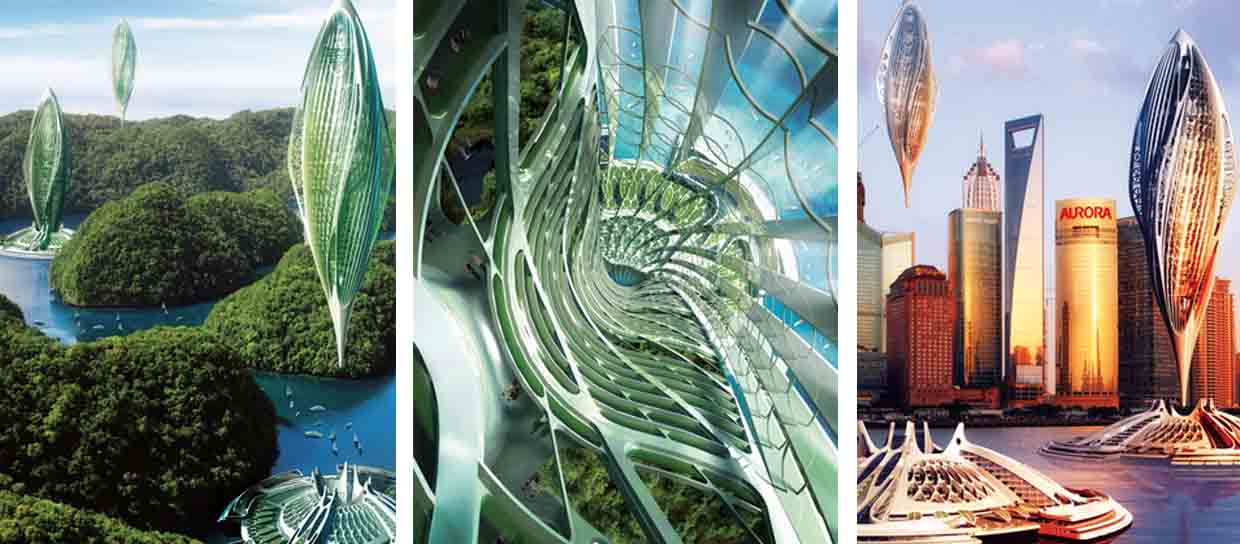

It requires fewer infrastructure systems than our existing modes of movement and thus would not harshly affect our natural systems. It is able to link areas of remote connectivity because of its spatial system having the potential to be able to transit without much existing infrastructure. Hydrogenase is a jumbo jet vessel that flies at an average height of 2000 metres. This cargo measures almost 400 metres high for 250,000 m3. It can carry up to 200 tons of freight at 175 km/h. With its bio-mimicry inceptions, this inhabited vertical airship sets down in the heart of a floating farm of seaweeds that reloads it directly with bio-hydrogen. These two interdependent entities are both nomad and organic, the first one flies in the sky and the second one on the seas and oceans.

We must strive to generate a more sustainable form of movement system

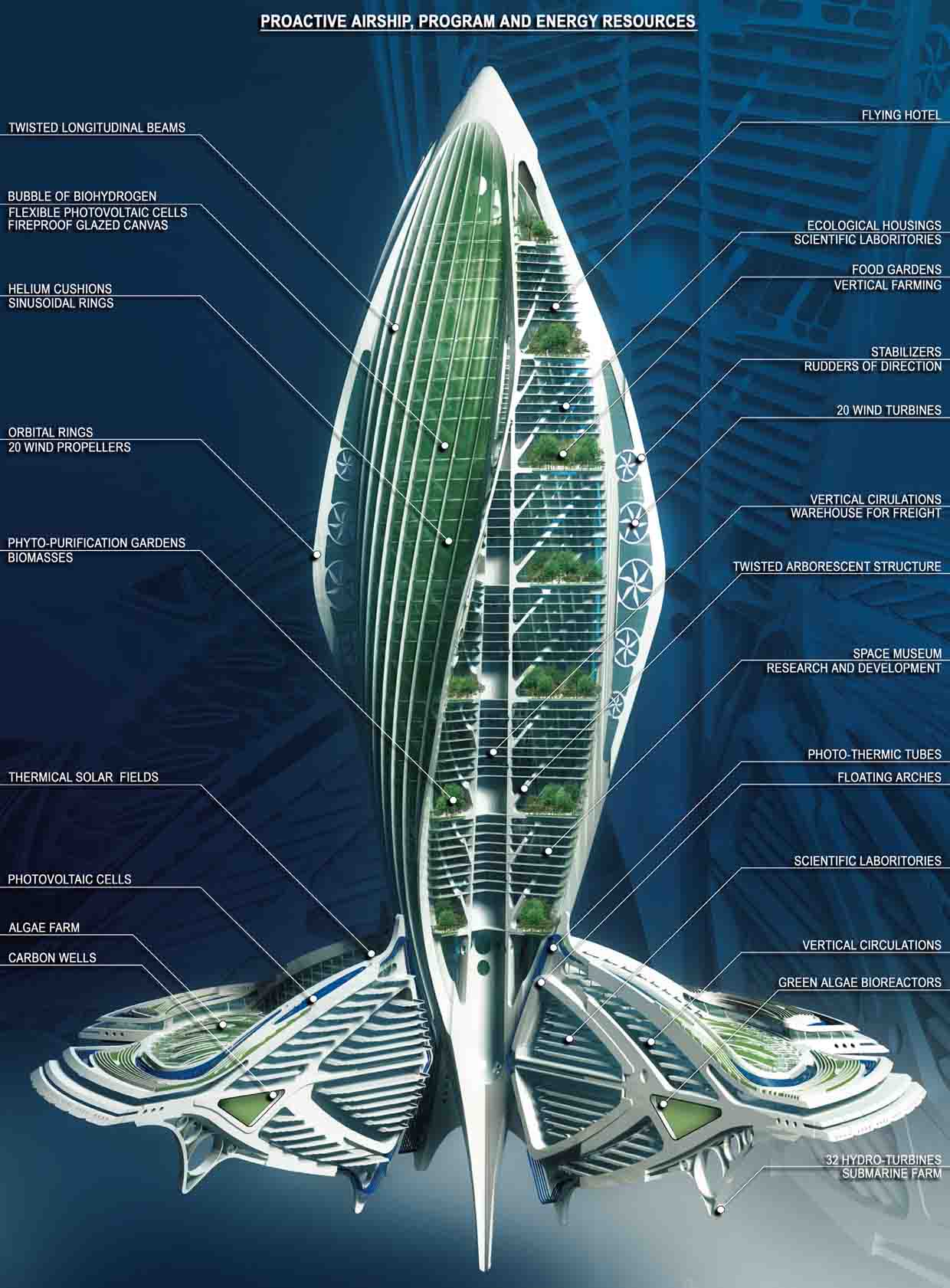

THE PROACTIVE SHIP FLOURISHING IN THE AIR

The semi-rigid unpressurised airship stretches vertically around a spine that air-dynamically twists on more than 400 metres of height and 180 metres of diameter. The spaces divide in the shape of petals that welcome respectively the main sectors of activities: housing, offices and entertainment.

These inhabited spaces are included between four great bubbles inflated with bio-hydrogen. These bubbles are made with a rigid hull in light alloy shaped with twisted longitudinal beams linked together by wide sinusoidal rings. A cone finishes every end and the one at the bottom, the most sharpened one, carries the stabilisers and the rudders of deepness and of direction. A double layer of waterproof, fireproof, glazed canvas – to reduce the resistance to movement – covers this framework. The in-between section is divided into slices in which there are small balloons full of helium. The helium mattress in the periphery protects the balloons of bio- hydrogen and helium.

It is heavier than the air and moves about using the Archimedes’ thrust. The subtle twisted aerodynamic enables it to reduce the oscillations of the limited layer. The fact that it is heavier than the air enables it to descend faster without having to eject gas. Moreover, this mechanism is based on the compression and the decompression of the biogas. Hydrogenase can thus be lighter or heavier according to the desired needs and the height.

The inflatable bubbles of the airship are glue- backed with flexible photovoltaic cells; the four wings of the vessel are each inlayed with turbo- propellers with recuperation of energy. The 20 wind propellers are articulated around orbital rings that enable them to go from the horizontal position at take-off to the vertical position assuring the vessel a navigation speed of 175km/h.

The inhabited spaces integrate by step vegetable gardens recycling the used waters. Nothing is lost; everything is recycled and transformed.

At the apex it is built in lighter and more resistant composite materials (fibreglass and carbon fibre) in order to reduce the weight of its structure at the maximum. The fitting is thus maintenance free, in nano-structured glass inspired from the lotus leaf. This bionic coating also draws its inspiration from sharkskin that enables, without being toxic, to avoid the adhesion of bacteria whereas the four wings present irregularities of surface, as the finely beaded whale fins do, in order to reduce turbulence. The airship part of the project is an amalgamation of sustainable technologies and bio-mimicry initiatives.

This inhabited vertical aircraft incorporates a clean and efficient mobility system to meet the needs of the population

THE FLOATING ORGANIC FARM ON SEAS AND OCEANS

The floating farm is a true organic purifying station composed of four carbon wells in which the green seaweeds recycle our carbonated waste brought by the ships. This is directly dedicated to organically feed the biohydrogen for the airship. It acts as the fuel supply and resembles a weaving of fine amphibian laces.

It is set up as much underneath as on top of the sea surface and respects the quadripartite sharing out in petals of the whole Hydrogenase project. Continuing the four wings of the pneumatic tower, four great arches form a circular platform and distribute vertically all the levels of the central ring. At the surface, thermal and photovoltaic solar shields cover these arches whereas under the water they are set with 32 hydro-turbines transforming the tidal energy of the sea streams into electricity.

This farm forms a radiant plan. The whole set forms four gardens dedicated to the accelerated photosynthesis, which we access through the marinas setting the exchanges between this floating city and the surrounding coasts.

MIDDLE: Inside view

RIGHT: Aerial perspective on Shanghai skyline

A SUSTAINABLE MODEL OF MOVEMENT

As Vincent Callebaut Architectures put it: “Hydrogenase is thus a project of environmental resiliency that will enable us to invent a clean mobility according to a cradle-to-cradle cycle respecting our planet by also assuring the technological evolution of the human adventure. By imitating the processes of natural ecosystems, it deals with reinventing the architectural processes to produce clean solutions and create an industry where everything is reused, either back to the ground under the shape of non toxic organic nutrients or back to the industry under the shape of technical nutrients able to be indefinitely recycled.”

Our cities are based on the patterns of mobility and an optimistic narrative of the spatial layout. Such projects in the urban environment of our cities would usher a new paradigm of newer, safer movement systems with due respect to our natural systems and environment.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS: VINCENT CALLEBAUT ARCHITECTURES, BELGIUM

Comments (0)