Australian cities have, over the last 150 years, successfully planned, developed and maintained parks, gardens and sporting areas within their central areas. Adelaide’s ring of parks is a great example of long-term vision and consistent improvement of inner city parklands.

The development and maintenance of public space in city streets and urban squares is less confident and successful when compared with much older cities in Europe that were operating for centuries before the era of the motor car. Many have squares and public spaces that continue to be used and maintained in much the same way as they have for many decades and even centuries.

Melbourne City Square

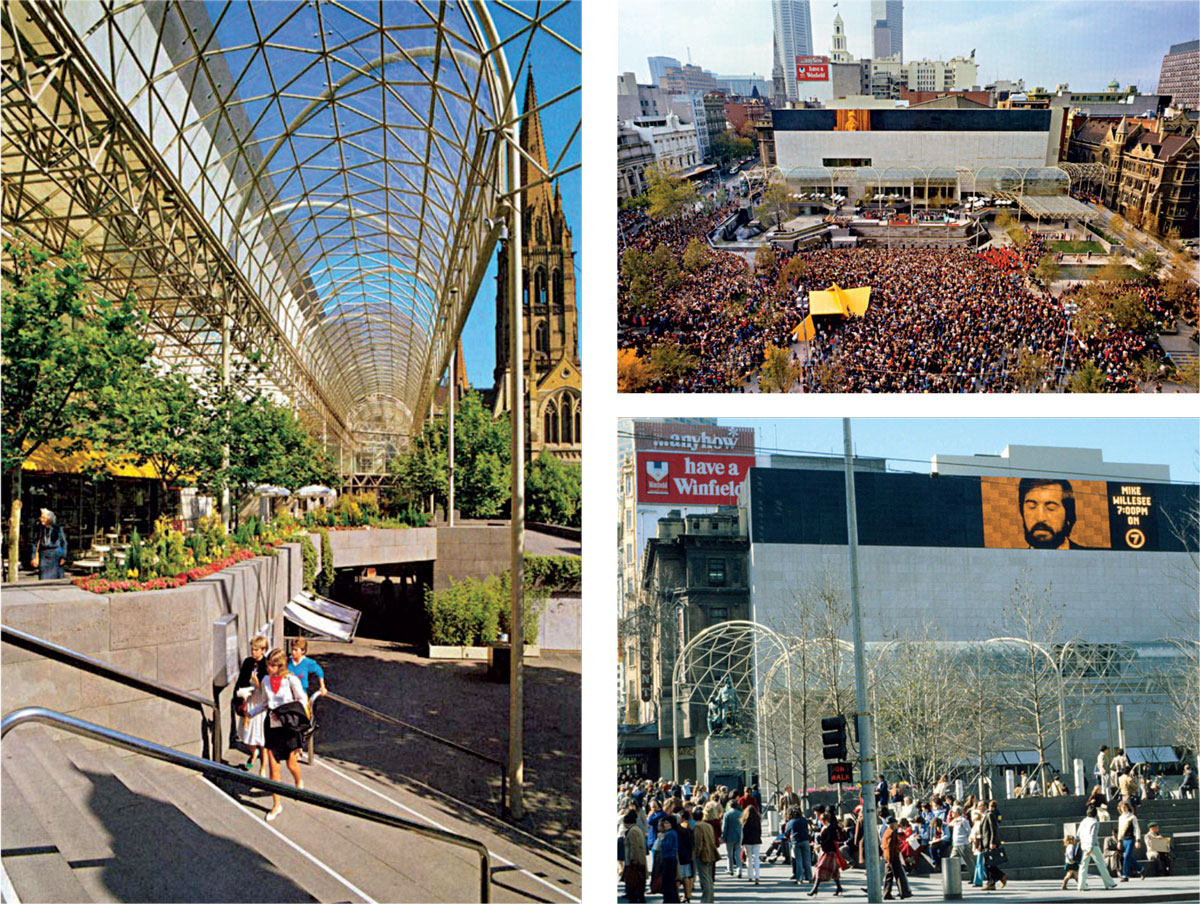

Melbourne yearned for a ‘European’ style square in the last half of the 20th century. The first was developed and inaugurated by the Queen in 1980 as Melbourne City Square, at the heart of the city grid on its main civic spine between the Town Hall and St Paul’s Cathedral. Its award-winning design was developed through a public competition won by Denton Corker Marshall in response to a detailed brief requiring an active space for large gatherings, celebratory and political, with greenery and meant for casual use. It was a high-quality space with trees, fountains, a video screen, public art and commercial tenancies developed and run by the City of Melbourne.

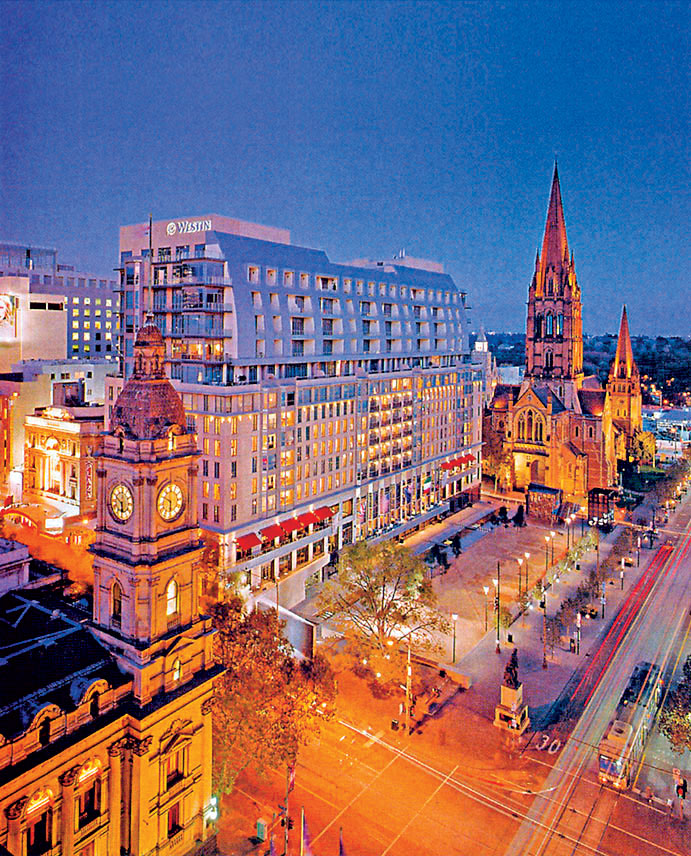

Within a decade, this space became rundown and the city started to promote the redevelopment of the site as a reduced and simplified public space and as a forecourt to the new 5-star Westin Melbourne Hotel built along the eastern third of the square over a five-level underground car park.

The City of Melbourne argued the original design was at fault but, in my view, the Council’s inept management of the space, including the commercial tenancies and unwillingness to properly fund its operation, as intended, led to the Square’s eventual redevelopment.

The more modest, low-risk version of the square was developed by the city and it has performed a lesser, but still effective role, as an urban square.

Right Top: Melbourne City Square mark 1 on the day it was opened by Queen Elizabeth in 1980

Right Bottom: Video screens at the city square

Ironically, this second and equally expensive public space is now closed and the car park below has just been demolished to enable a new metro station. Two versions of this square that were built at huge cost to the taxpayer, have come and gone within 40 years.

Federation Square

The reconstruction of a much reduced City Square in 2000 was partly compensated for when the State Government created a new site along the civic spine one block south. This new site, facing the iconic Flinders Street Station, was created by the demolition of some much disliked government office towers and decking over rail tracks, to help link St Paul’s Cathedral and the city centre to the Yarra River.

Federation Square was developed and opened in 2002 as a result of a design competition won by LAB Architecture Studio. The brief called for incorporation of public arts uses and venues including galleries, a museum of film and digital culture and an Aboriginal cultural centre, together with visitor information and cafes and bars to support the public space.

Bottom Left: Artist’s impression of the new Apple building

It was jointly funded by the State government and the City of Melbourne and set up and managed as an independent corporation. The design was contemporary and controversial, but has now gained wide acceptance and is a symbolic space for the city that is visited and well used by around 10 million tourists and Melbournians each year.

Federation Square is run by Fed Square Pty. Ltd., a company managed by a board of directors and with around 50 employees, owned by the State Government and has a charter to manage and maintain the site as a cultural hub for Melbourne. It has a significant annual budget of around $28 million and operates on a close to break-even basis, spending revenue from rentals and events on maintenance, security, management and public event programming.

This appears to be a very successful model for delivering an active, vibrant public space and has certainly proved better than previous attempts by the City of Melbourne at Melbourne City Square; however the management structure is based on quite ambitious corporate goals.

This has been made apparent by an announcement in the last days of 2017 – when it was least likely to attract attention – that the State Government had made an agreement with Apple to allow them to demolish a river edge building at the heart of the square, to enable a new Norman Foster designed Apple Flagship Store to replace it.

This deal with Apple appears to have been done two years earlier in secrecy with the terms remaining confidential. Only limited views of the design are available for public scrutiny and the design appears to be unsympathetic to the style of the square while possibly improving pedestrian connections between the heart of the square and the river edge. The State Government argues that it will increase declining visitation to the square and will no doubt generate a substantial increase in revenue.

This announcement has created a strong negative reaction from the public and the professionals because of the secret decision making process, the apparent incongruity of the design and the appropriation of Federation Square by Apple, which is Melbourne’s primary urban public space. With a State election coming up towards the end of 2018, it could become an influential issue for voters.

The Government’s stand is that Federation Square is in need of revitalisation and extra income and that the first Apple flagship store in the Southern Hemisphere will attract more visitors and provide a better educational and technological exchange with existing public tenants, including the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, National Gallery and the Koorie Heritage Trust; thus reinforcing, rather than competing with, the cultural objectives of the square.

Lessons from Melbourne on developing and managing urban squares

What lessons can be drawn from this simple history of Melbourne’s attempts to develop urban squares in the city centre over the last 40 years?

1. In a democracy like Australia, investment in highly programmed public squares is an expensive and risky business and likely to be transient unless a suitable management system can be provided and consistently applied over time. Melbourne City Square totally failed this test and Federation Square is now under redevelopment pressure after just 15 years.

2. Significant income from supportive commercial uses is necessary to maintain buildings and spaces and run events and activities. Alternatively, the government must be prepared to allocate regular funds in an apolitical manner over the life of the space. Ambitious events will often require equally ambitious budgets to cover them.

3. Management of events of this nature must allow for a wide range of community, political and cultural values to be freely expressed through events and casual use by a wide spectrum of society. They should not be managed in a way that allows commercial supporting uses to displace public activities and values.

4. Expenditure on other less ambitious public realm improvements within cities such as recovering road space from cars to better provide for pedestrians, cyclists and incidental green space across wide areas may be a better way to invest public money to provide long term value for the community.

Melbourne has transformed its central area over the last 40 years through fairly consistent urban design policy that has seen residential use dramatically increase and universities expand, adding to street life.

Public transport including trains, trams and buses are gradually displacing cars. Walking in the laneways and major streets is slowly being prioritised and bike use is increasing, though it is far from safe or well catered for, as yet. Much has been done to open up the river for pedestrians and consistent development of street trees, furniture paving and lighting is possibly one reason why Melbourne is often considered a very liveable city. This work never stops as central Melbourne continues to increase in density and resident population. Continued improvement of public space is essential to provide space and amenities for the many thousands of new residents living in high rise towers.

PHOTOS: DREW ECHBERG

Comments (0)