The definition of an Indian street has evolved over time from being a hub of heterogeneous social activity to simply being a carrier of automobiles. The visual that this conjures up is of a boring, chaotic and an unwelcoming space. Contrary to this, on deeper reflection, the Indian street is also synonymous with being vibrant and buzzing with activity. This is because the street, in an Indian context, is at odds with its function, resulting in a confused state of affairs that is reflected in the chaos that we see today. Pune, like any other city in India, is confronted with issues of ever-increasing numbers of automobiles resulting in major traffic snarls. Unfortunately, the response to this issue has led to the development of our streets on a highway model with wider carriageways to allow for uninterrupted flow of traffic movement. The narrative of the street has steadily shifted towards prioritising cars, which directly influenced city planning in a big way. Pedestrians have been the most affected user group and as a result have been pushed furthest away from the centre of the street, with very little space dedicated to them.

The Human Dimension

“A great street is a public place that tempts to slow down people, to stop, to chat or to simply watch the world go by, a place that enriches the lives of those who use it.” – Gehl

Like many other cities around the world, Pune too has grown from a tiny settlement on the banks of a river. With this settlement at its centre, the city, organically, grew radially creating a web of interconnected network of streets. The historic core is a complex mesh of streets and lanes locally known as aalis punctuated with squares and open spaces.

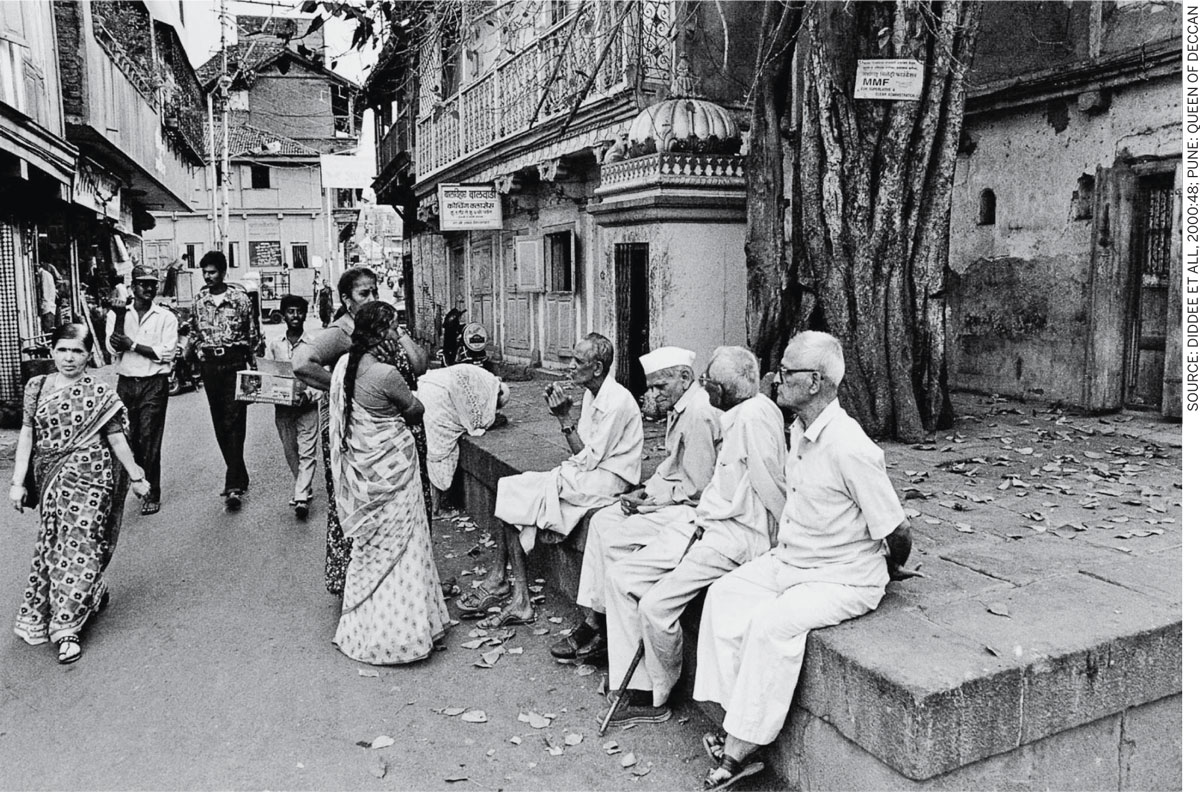

The streets then developed on a pedestrian scale with narrow widths. These aalis have always functioned as shared streets with a built-to-edge character creating ‘street walls’. Streets are an integral part of our built environment as spaces for social interaction. A beautiful example of this in the old city of Pune is the occasional ‘Paar’: a raised platform under a venerable tree used for informal conversations, a metaphoric expression of a Node. Kevin Lynch, in his book Image of a City, talks about ‘imageability’ of places using Landmarks, Edges, Paths and Nodes.

Even in the most congested of cities, people have always found ways to ferret out small spaces for social interactions. These lanes in the old, sometimes almost decaying parts of our cities can teach us so much – the significance of pervasiveness of the human dimension.

Traditionally, streets were a part of the public domain, typically used as an extension to people’s homes. A democratic space meant for all that was used as a public space and a means for people movement. The human dimension played an important role in maintaining the vitality, safety and cultural identity of a street. In today’s context, this leads us to think and question, whose street is it anyway?

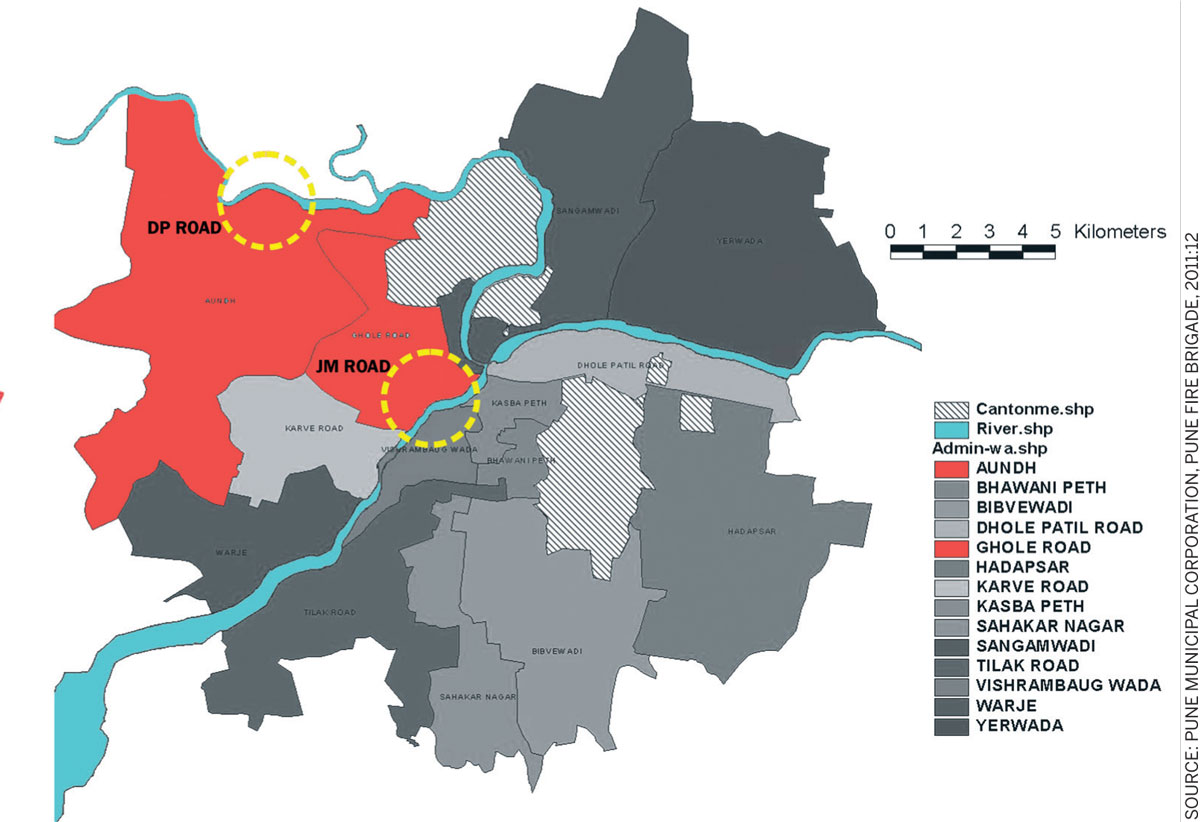

The Pune Chapter

Indian cities are gradually making huge efforts to improve the quality of the built environment especially in terms of their transport infrastructure. Pune has much to contribute to this movement as it has a lot to gain by reinventing its identity. It is a rare city of paradoxes; it retains the images of being a quintessential Maharashtrian city and that of a modern industrial metropolis. It has had multiple identities over time from being the ‘Queen of the Deccan’, the ‘Cultural capital of Maharashtra’, ‘Oxford of the East’, ‘City of Cyclists’, ‘Pensioners Paradise’ to becoming an ‘IT-BT Hub’. The city’s physical structure in terms of its form, the urban grain, network of interconnected streets and pleasant climate makes a perfect setting to demonstrate how to make its streets people-oriented.

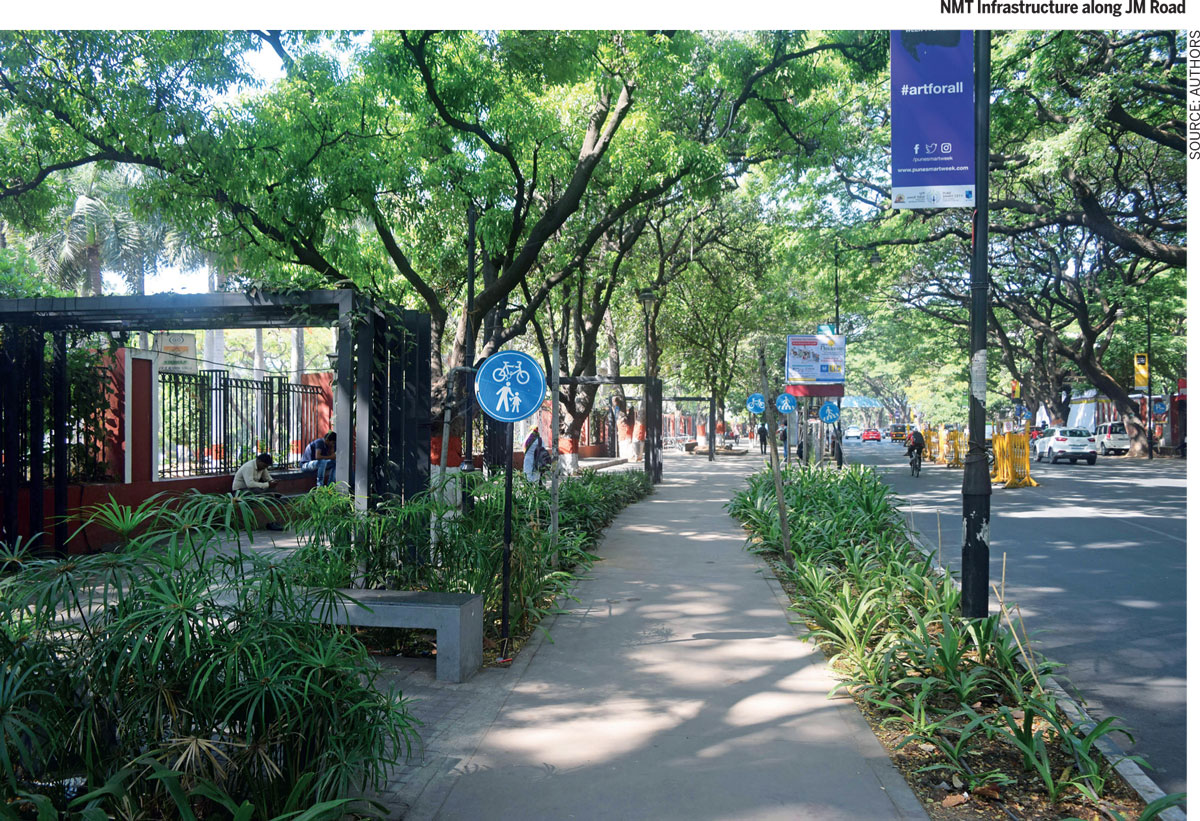

Pune has been working to improve its pedestrian and cycling infrastructure by redesigning roads as Complete Streets to have dedicated zones for all user groups.

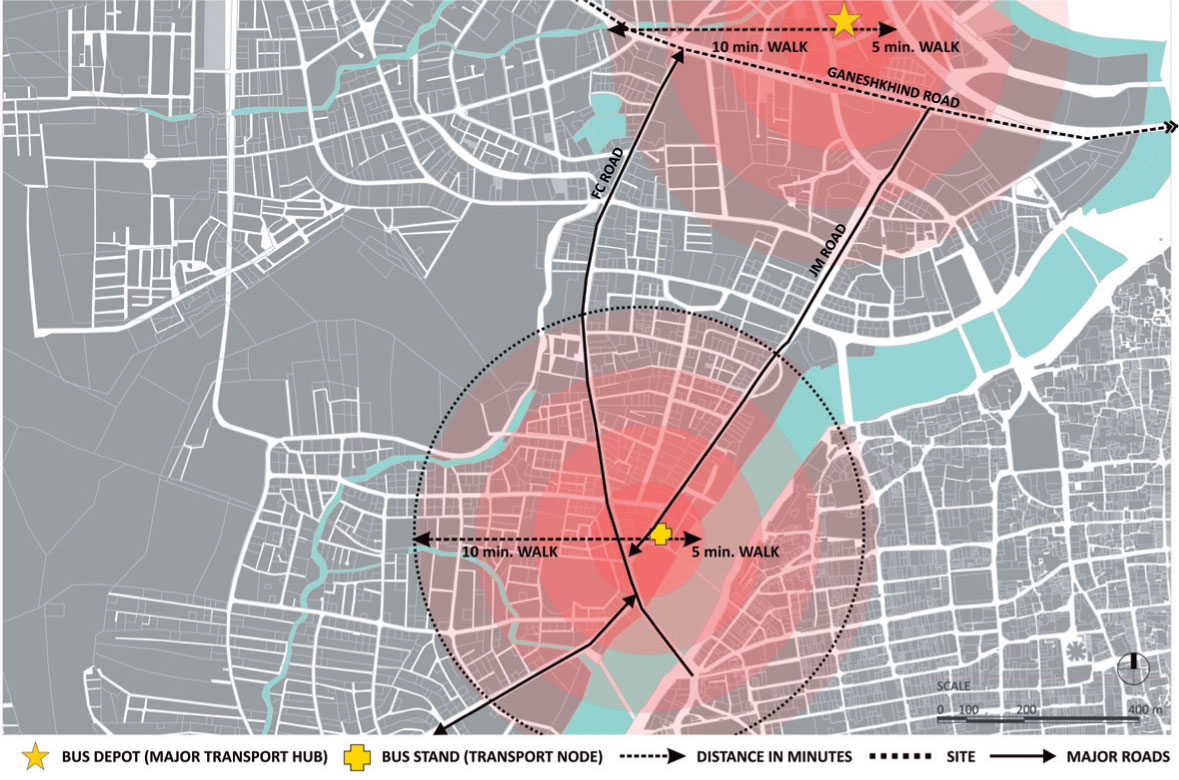

It began by improving connectivity by creating a better network of roads equipped with infrastructure for non-motorised transport (NMT) under the city-modernisation scheme, the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) in 2009. One such example is of Jangli Maharaj (JM) Road, one of the two important arterial roads in the heart of Pune, which is also one of the few remaining boulevards of the city. The other, FC Road, gets its name from Fergusson College, a 130-year-old educational institution. These two roads run north-south connecting different neighbourhoods. The JM and FC Road precinct is a hub for major commercial and retail activity with a number of reputed educational institutions and some of the old residential areas of Pune. The area also has cultural centres, a large public garden, temples and a transport hub in the vicinity. This brings in a varied mix of people and vehicles to the area throughout the day, seven days of the week, with the two-wheeler traffic being the highest.

Under the ‘Neighbourhood Upgradation Plan’, which aimed at solving traffic woes of the area, these roads were redesigned to have wider footpaths, dedicated cycle tracks and bus lanes with one-way traffic movement of vehicles. JM Road, FC Road and Ganeshkhind Road were planned to function as a triangular loop to manage traffic. However, these proposals were not implemented as intended and only the suggestions of converting vehicular movement from two-way to one-way was executed. The street was widened from 24 metres to 30 metres, medians were removed and in turn, the pedestrian refuge islands disappeared. This led to wider carriageways with increased traffic speeds and unsafe pedestrian crossings resulting in an increase in the number of accidents.

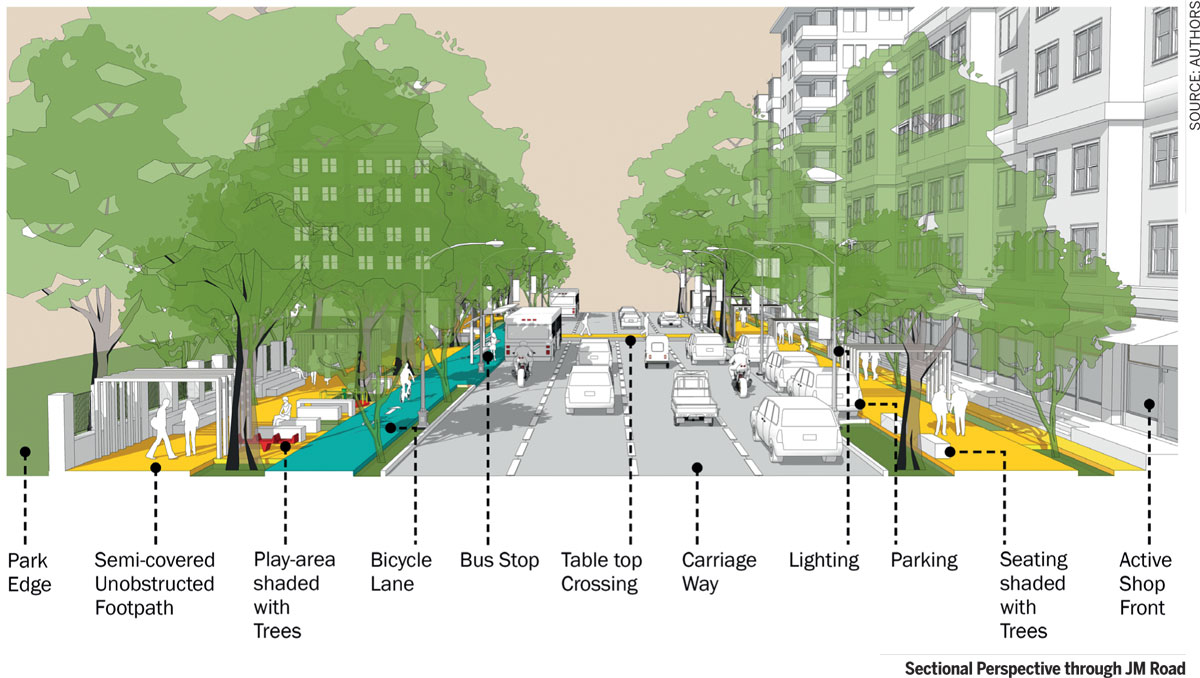

The second impetus to this initiative has been the SMART City Mission under which the Pune Streets programme was developed, which identifies a 100 km street network for redesign. In the first phase of construction the 1.8 km JM Road stretch with right-of-way (ROW), ranging from 23-36 metres was developed in two different sections. A 1.5 km stretch features clear, continuous footpaths with cycle tracks and dedicated parking zones and the portion abutting the garden and the cultural centre – a stretch of 300 metres – has a more elaborate proposal with wider footpaths and cycle tracks with landscape buffers, elaborate seating and small play nooks.

The design certainly reclaims the pedestrian domain, although it falls a little short of what can make it an all-inclusive proposal. For example, traffic-calming measures are missing, making it unsafe for pedestrians to cross over; the carriageway width could have been modified at junctions and at tabletop crossings to accommodate this.

The reclaimed space adjoining the park has opened up greater opportunities, which can extend to the river promenade in the future.

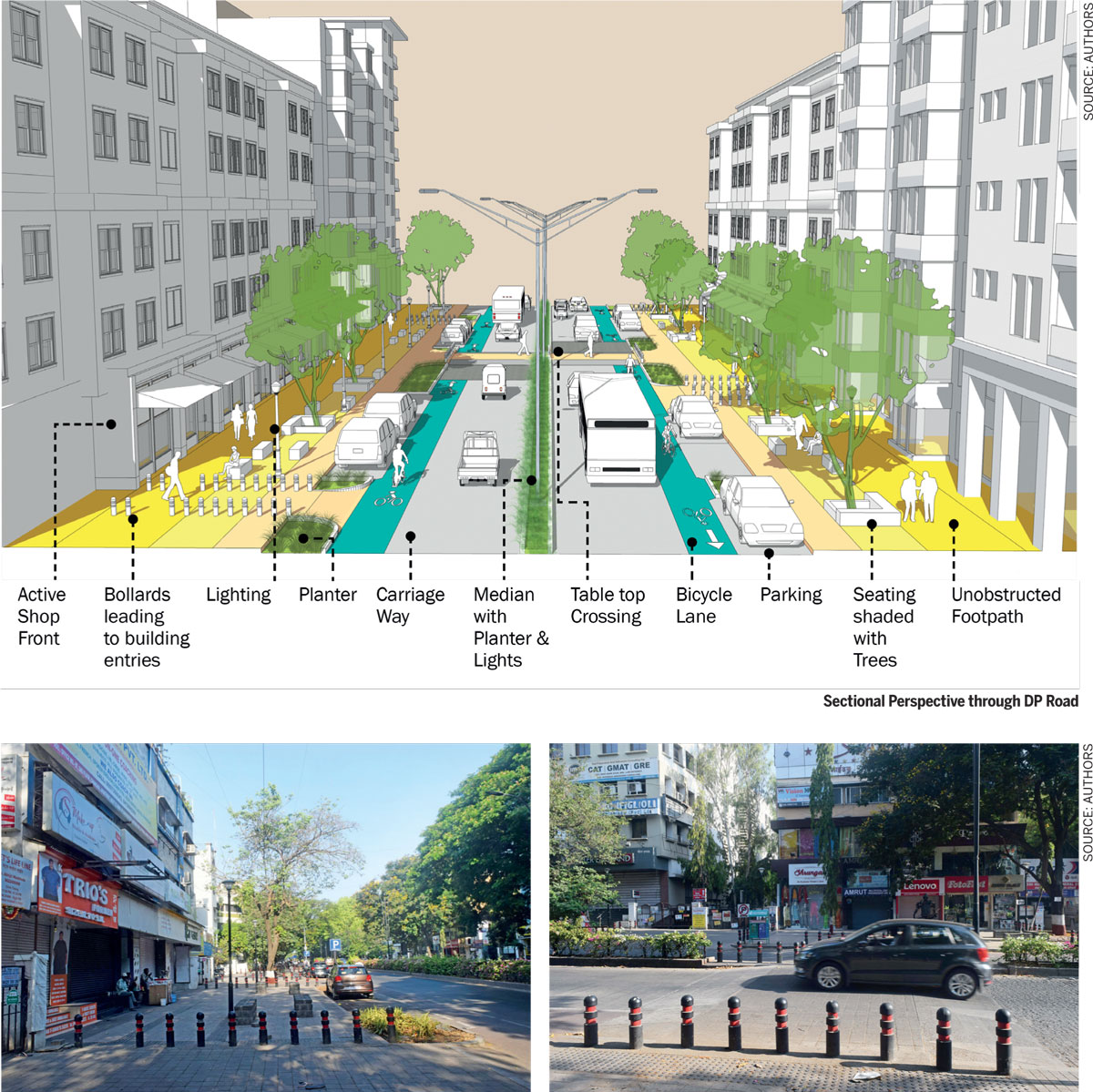

Another example is from a fairly newer area of the city, called the Aundh DP Road. This street is a part of the Area Based Development (ABD) marked out for Pune under the SMART city initiative. This example stands out for its public participatory approach towards renewal of the street. A charrette to engage with the stakeholders led to a tradeoff between the shopkeepers, designers and the authorities. The shopkeepers agreed to merge their shop frontages with the sidewalks to create a wider and continuous pedestrian realm, which is peppered with ample seating and interesting artwork. Additionally, keeping the shopping experience in mind, parking bays for two-wheelers and cars have been provided for shoppers using vehicles. A shared cycle track of approximately 1.5 metres runs along the carriageway, which is wide enough to accommodate the ‘wobble room’ of a cyclist.

The ABD proposed a public bike-sharing scheme under which docking stations for these cycles are also provided on this street. A lot of attention has been given to the details in this case. For example, the footpath continues at the same height even with multiple property entrances for uninterrupted movement of a pedestrian with access through ramps from the carriageway. Another detail is the variation in texture for a portion of the road before the raised crossing to reduce vehicle speeds as a traffic calming measure. Universally accessible routes are clearly demarcated throughout the entire route. The DP Road stretch has become an active and vibrant space for a great shopping experience.

|  |

Right: Traffic calming measures

The transport modal share shows a high number of trips on foot, which suggests that people are walking. But who are these people? When we talk about walkability in India, we are talking about a group of people, the urban poor/the ‘captive pedestrians’, who walk because they cannot afford to or do not have access to transport modes. It is important to understand the user group and, for a place to become successful, the design needs to be inclusive. At the same time, we need to encourage the wider group to also be a part of this system. Where parameters of density, social imbalance in terms of economy, notions of caste and creed still play a strong role in city dynamics, it is a challenge to motivate more people to walk and to make it a trendier option. It is promising to see efforts being made to improve the pedestrian infrastructure of the city. However, it is important to see this happen at a faster pace covering larger zones with more connected and a continuous network to have greater impact rather than piecemeal projects. The positive that cannot be overlooked from these examples is the effort, the intent, more importantly the value and the experience that this gives the locals. For a cultural shift to happen it is important for the users to recognise the significance of this change.

Comments (0)