The multitude of sights, sounds and smells of a city in India can feel like utter chaos, but they often coalesce into the most memorable and identifiable images of a city or neighbourhood. The workers of the informal sector are key actors of this kind of organic place making.

A neighbourhood may be known for a specific item or activity, characterised by agglomerations of certain types of livelihoods that wind between formal and informal spaces of the city. For example, the sights of a market selling incense, flowers, ‘fancy items’ and statuettes for the devout outside Madurai’s historic Meenakshi temple; the sounds of SP Road, nicknamed ‘spare parts’ road, in Bengaluru, that sells all manner of electronics and miscellaneous components at wholesale rates; the beguiling scents of the street food and eateries of Mohammad Ali Road in Mumbai, especially during Ramzan nights. These are only a few examples of the sensory and experiential contributions that create the dynamic sense of place in cities, thanks in large part to the activities of informal workers, those practicing traditional livelihoods, and other small-scale enterprises. After all, 90% of India’s total workforce are employed under informal arrangements and this includes close to 80% of urban female workers, as well as 80% of urban male workers.1 UN Women also notes that over two-thirds of the employed population are in vulnerable employment and so are especially susceptible to the impacts of the pandemic. Our responses under COVID-19 left people behind in many ways, placing hugely disproportionate burdens on certain groups.

‘Informality’ is a broad characterisation that touches a very mixed group of people, but this very diversity is responsible for the distinct character and basic liveability we enjoy in cities. Many are engaged in the more mundane but essential trades that get taken for granted but are responsible for the conveniences of daily life. Examples include the fruit and vegetable sellers sitting behind piles of colourful, region-specific produce, or the local scrap collector trawling the streets with his cart and calling out in piercing tones to households for their paper waste and cardboard. Similarly, over 500,000 homeworkers are a crucial link in India’s domestic and global supply chains for garment and textiles alone (Sinha, 2019). Many more go unseen, behind the scenes, keeping the city clean, moving, supplied, repaired, growing and running.

From early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic thrust to the forefront the topic of spatial management for public health. It also reinforced the fundamental spatial link between livelihood and housing, between the promise of economic upliftment and the compromises made by people around shelter. In centuries past, town planning as a discipline was also born out of a concern for public health. It aimed to contain the spread of diseases and ensure good sanitation, ventilation, light and management of shared space in worker housing and urban settlements. With COVID-19, (at the time) a little-understood but deadly virus, slowing its transmission became governments’ first priority. Healthcare systems scrambled to brace themselves against spiraling caseloads. Borders shut, both internationally and domestically, and people’s movement was strictly prohibited, leaving an echoing silence in once-busy streets and markets.

In India, with only four hours’ notice, the first national ‘lockdown’ was imposed in March 2020, statutorily confining people to their homes for increasingly longer periods. All modes of travel had been summarily halted under threat of punitive State action. People were told that the role of citizens was key to stopping the virus; we must stay home, practice ‘physical distancing’ and ‘social distancing’, and ‘work from home’ as the threat stretched from days, to weeks, to months. Uncertainty for the future, and helpless waiting, became the name of the game.

Many [informal workers] go unseen behind the scenes, keeping the city clean, moving, supplied, repaired, growing and running

By the time the third and fourth lockdowns were announced, everyone was familiar with the drill. Living alone in my one-bedroom apartment, the day consisted of quiet meals fit between a series of virtual work meetings, looking forward to a 5 o’clock tea break to enjoy the golden hour. The window overlooked a city playground, a rare parcel of wide, open space holding fast against the gridlock of narrow streets that bristled with colourful but modest two- and three-storeyed apartments. Tucked into one corner, a square of outdoor gym equipment lay uncharacteristically empty, and piles of sand and concrete pavers told the story of park designs put on hold, waiting for the world to start again.

In the midst of these expected sights, a bright splash of blue had appeared magically overnight. It was the temporary shelter put up by a family, presumably transient workers from the construction industry, and likely to be briefly employed by the city municipality or public works department. Over the following days and weeks, the tent-like construction gained features of an established home. Laundry hung on lines strung between the trees that lined one edge of the park and nearby black marks indicated the remnants of a cooking fire. More tents followed, with more families and the formation of shared living patterns. Makeshift wooden porches were added to the front of some tents. Storage and wash areas were designated to the side. Women bustled about, doing the communal cooking and washing. The younger girls were enlisted to reluctantly collect firewood and wash utensils. Men carried heavy buckets of water from the public drinking fountain and toilets at the far end of the playground, almost half a kilometre away. One night, a bare white lightbulb cast a blue glow from inside one of the shelters, soon followed by more. One row of tents became two, then three. ‘Streets’ and a square had developed. The whole grouping took up less than a tenth of the playground, and only a few months had passed since the appearance of the first tent.

The relationship between planning and housing informality in India has historically been circumvention, avoidance or regularisation after the fact. Planning enforcement is often presented as a technical, depoliticised endeavour within this planning imagination, and we see it characterised in our cities by urban cleansing, evictions and demolitions. Informal housing and informal livelihood fall within the same conversation because the kinds of housing choices that are made by the urban poor are driven by the nature of their work: something inadequately accounted for in formal planning paradigms. Livelihood goes hand-in-hand with housing; the precarity of one affects the other – and the proof of it lay in the migrant workers’ exodus from cities to their hometowns and villages in March and April 2020.

The ‘decisive action’ to contain the spread of the virus had not been accompanied by basic support or relief packages designed to reach those most in need

This ‘invisible’ brewing crisis came to a head in public consciousness as images of migrant workers and their families, with children, pregnant wives and elderly parents, spread across social media and news channels. Particularly shocking was the sight of desperate people taking to highways on foot and bicycle, resolved to make the impossible journey of thousands of kilometres across the country in the blazing summer, in hopes of reaching the relative refuge of their home villages. To the nation’s collective horror and shame, it became apparent that the ‘decisive action’ to contain the spread of the virus had not been accompanied by basic support or relief packages designed to reach those most in need. Any assessment of the impact of lockdown restrictions had either completely missed or disregarded the realities of hundreds of millions of Indians having little to no buffer against the cost of containment measures: pandemic responses ‘burdening the poor’ as Sharma and Yount (2020) write.2

Major cities like Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru have large populations of migrant workers, and a recorded 11.4 million of them (as per government data) returned to their home states following the first lockdown.3 Circular migration, where a person seasonally or periodically moves between their home and host locations, is a well-known feature of the Indian labour market. So is the difficulty these migrants have in accessing healthcare, social security and welfare benefits under these conditions of transient relocation.4 The Stranded Workers Action Network (SWAN) was able to share experiences of daily wage workers from across India and to report on their distress while attempting to link them to help. Journalist-turned film-maker Vinod Kapri chronicled from close quarters the trek of seven Bihari migrant workers from Ghaziabad to their hometown, in book-form, 1232 km: The Long Journey Home, and in a documentary. 2011 Census data, though considered to be an underestimate, found 38% of the population – 456 million persons – to be migrants, a growing number from the earlier Census. Though most migrated within their home state, those moving between states predominantly traveled out from states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, and into the Union Territory of Delhi and the state of Maharashtra, and most often for work.5

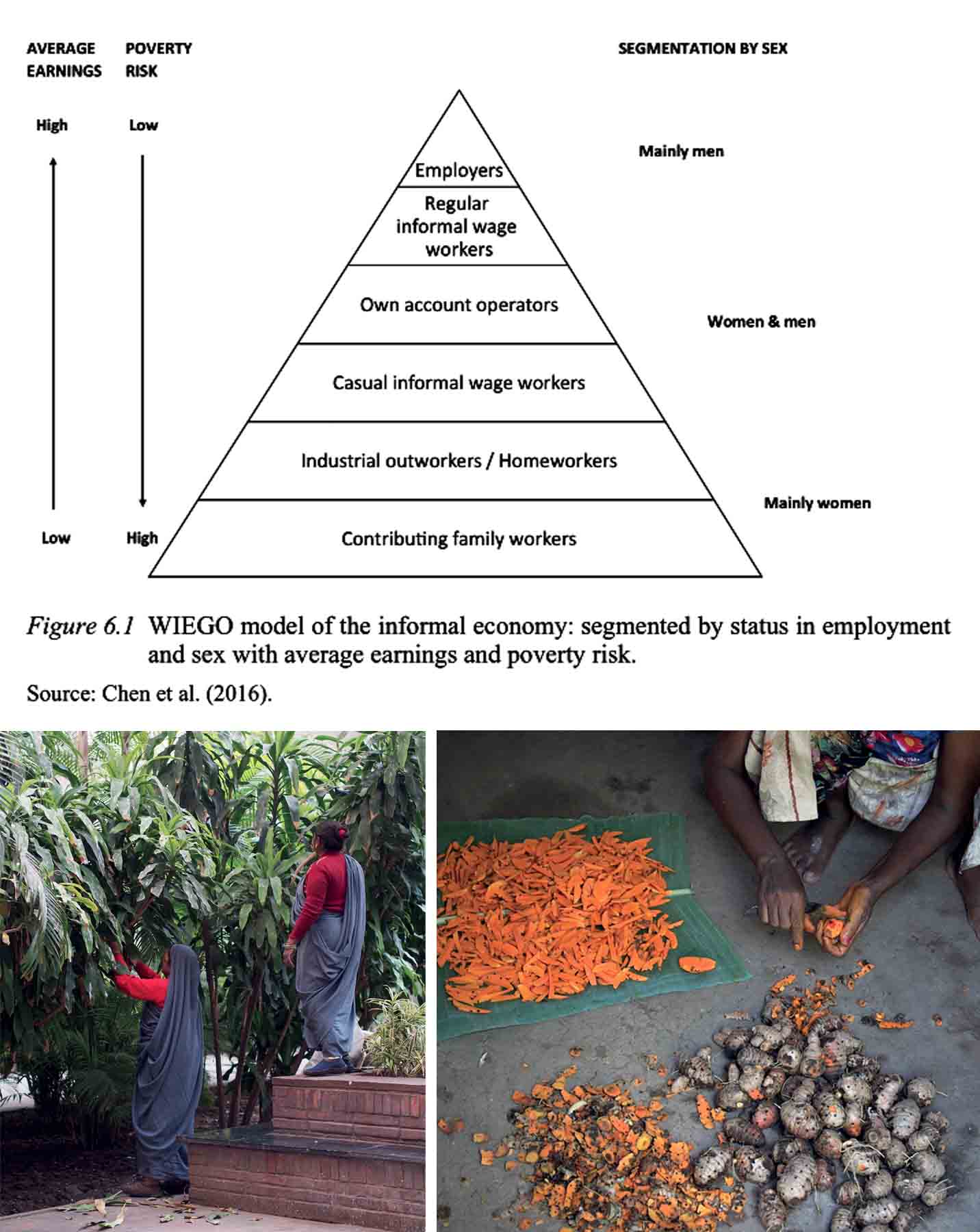

Informality is similarly a long-standing part of the Indian economy. Informal workers face several systemic sources of costs and risks, including the dominance of stigmatising narratives, policies and laws biased against informal work, lack of access to public space, public services, public procurement, and a lack of legal recognition and right to representation in policy-making processes. Some have argued that the State is itself a driver of the informal economy in many ways. To quote from Chen and Carre (p24, 2020), ‘The state… decides which aspects of the informal economy to turn a blind eye to, which to tolerate or which to get rid of; and which aspects of the informal economy to support or promote.’ This has shaped particular forms of informality through our attitudes, regulations and policing – labelling them as illegal, criminal, problematic, as low-end survivalists or a non-productive burden on the economy. Informal work in such a context not only operates outside of labour protections while facing punitive action, but is relied on by State and formal sector employers and workers, as it actually fosters growth.5

Bottom left: Two women workers maintain an institutional campus Bottom right: A woman prepares turmeric by hand to sell at the local market |

SEWA Bharat (the All-India Federation of Self-Employed Women’s Association) and WIEGO (Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing) published the stories of their members from various trades (such as office cleaning staff, rag-pickers, handicraft artisans), describing their lives under lockdown and on-going challenges.6 Many households faced starvation, with no income to spend on monthly supplies nor even to buy smaller quantities for immediate needs against credit. Local shops and neighbourhood markets, the main source of these essential supplies and an essential buffer against food insecurity, were shut down. At the same time, rations were inadequate and difficult to access, even through government welfare programmes and the public distribution system. With no end in sight, dwindling demand for work, no public transportation to reach distant workplaces, no school for children and limited household space to be shared between entire families, the situation was extremely bleak.

Similarly, a report by researcher Geetha Menon for the Domestic Workers Rights Union (DWRU), Bruhat Bengaluru Gruhakarmika Sangha (BBGS) and Manegelasa Kaarmikara Union (MKU) revealed the plight of domestic workers in Karnataka during the pandemic; they faced unpaid wages and dismissal from work due to biases, fear and stigma of coming from informal settlements.7 Reports by SEWA on informal women workers, APU and others on frontline healthcare workers, and UN Women on the ‘shadow pandemic’ described further gendered impacts of domestic violence, livelihood precarity and medical expenses under the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Meanwhile, the Karnataka chapter of the All India Central Council of Trade Unions brought out a report on the condition of crematorium and burial ground workers in Bengaluru, as the pandemic saw such places across the country struggling to keep up with overflowing bodies. The majority of this worker group are already marginalised due to the caste-driven, intergenerational and deeply stigmatised nature of the type of work they do. While providing this essential service and facing incredible risk to their own wellbeing, they receive no statutory benefits, minimum wage payments, occupational safety measures or dignity of labour.8

These sources give us a glimpse into people’s vastly differing lives during the pandemic from the ground up. They are only a few accounts among many, but they push us to think deeply about who our cities are designed for and what daily lived realities are seen. They raise the question of how cities can be managed to better support the range of livelihoods and the needs of all its inhabitants, leaving none behind. Most of all, they invite us to recognise the scope, diversity and contributions that exist within what we call ‘informality’.

Informality was commonly thought of as a transitory phenomenon that would decline with increasing economic development. However, the evidence shows us that the informal sector has not disappeared. Rather, it has continued to grow and diversify alongside processes like urbanisation and globalisation. Old forms of informal work (as done by casual day labourers and home workers, often with low levels of education or formal ‘skills’) have continued alongside new forms of informal work such as temporary agency work and call centre jobs. Work on digital platforms from home, for example, draws on an educated labour force but provides no minimum wage, benefits for workers or social protections. Companies increasingly outsourcing and subcontracting work has driven a growth in temporary, piecework and part-time jobs. There is a workforce dispersion rather than collectivisation, and a devaluing of labour in emergent markets shaped by global bidding, rising short-term contracts and the gig economy.

It is important for urbanists to think about these shifts across livelihood, housing and employment landscapes because they directly

drive the choices people in cities have been making. They shape the decisions people will go on to make around their work and workplace, homes, travel and investments for the future. Urban local bodies, planners and service providers more often than not follow in the wake of development rather than guide it in a purposeful way. Cities, growing ever more complex, need to be recognised as the outcome of many more stakeholders than those ‘seen’ by formal systems and engage with them accordingly.

All photographs: Nandini Dutta

REFERENCES:

1.Raveendran and Vanek, 2020. WIEGO Statistical Brief No.24. Informal Workers in India: A Statistical Profile. https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/file/WIEGO_Statistical_Brief_N24_India.pdf

2.Sharma and Yount, 2020. Burdening the poor: Extreme responses to COVID-19 in India and the Southeastern United States. Journal of global health, 10(2), 020327. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.020327

3.Ministry of Labour and Employment, GoI, 2021. Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 1056 To Be Answered On 08.02.2021: Migrant Workers. http://164.100.24.220/loksabhaquestions/annex/175/AU1056.pdf

4.Nanda, 2020. Circular Migration and COVID-19. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3683410

5.Iyer, 2020. Migration in India and the impact of the lockdown on migrants. PRS Legislative Research. https://prsindia.org/theprsblog/migration-in-india-and-the-impact-of-the-lockdown-on-migrants

6.SEWA, 2020. SEWA Social Security Case Studies. https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/resources/file/SEWA-Social-Security-Case-Studies.pdf

7.Menon, 2020. The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Invisible Workers of the Household Economy. Domestic Workers Rights Union, Bruhat Bangalore Gruhakarmika Sangha, Manegelasa Kaarmikara Union and CIS. https://cis-india.org/raw/dwru-bbgs-mku-covid19-invisible-household-Workers

8.AICCTU-Karnataka, 2020. DIGNITY DISPOSED A Report on Crematorium and Burial Ground workers in Bengaluru during the COVID-19 pandemic. All India Central Council of Trade Unions. https://www.aicctu.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/AICCTU-crematorium-workers-report.pdf

9.Chen and Carré (Eds.), 2020. The Informal Economy Revisited: Examining the Past, Envisioning the Future (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429200724

Comments (0)