Interpretation of heritage sites from the perspective of landscape offers an immense opportunity to understand traditional knowledge systems. Documentation and interpretation of the city fabric was primarily driven by the need to understand the manner in which the water needs of the population were met. The process culminated in a revival of several water structures, not just through physical conservation, but also by activating the management of water systems in its historic setting.

Water has always been an extremely important element in the founding and growth of cities. During the early periods of human history, there was a direct and easily visible relationship between the settlements and water.

Cities typically grew along rivers, the fresh water source both structuring and sustaining the area.

The notion of water as an important structuring element of settlements is a fairly well established one. Traditionally, towns and cities have flourished in agriculturally rich zones, which by definition depended on efficient management of water.

The influence of water bodies – be they streams, rivers, lake systems or sea fronts – on the settlement pattern is clearly visible both in traditional settlements as well as in many latter-day developments.

|  |

Less explored is the facet of water resource management at the territorial level and implications of the resultant landscape on the attendant urbanisation. As cities grew in size and complexity, the influence of natural elements, specifically water, became less tangible.

Advanced societies built large cities that managed to perfectly balance the urban and natural aspects of the settlement. A shining example of one such city is Vijayanagara in Karnataka. Capital of a sprawling empire, the city form and its strategies to manage water remains a wonderful example to archaeologists and planners alike.

Hampi, the ruins of erstwhile Vijayanagara, is a World Heritage Site. It marks the remains of a 15th century capital city. The city of Vijayanagara, founded over existing ancient settlements during the 13th century, peaked in terms of scale and maturity during the 15th-16th centuries before being ransacked by an invading army. The region was abandoned following the attack and is now a prime archaeological site, with buried structures and settlements spread over 130 sq. km.

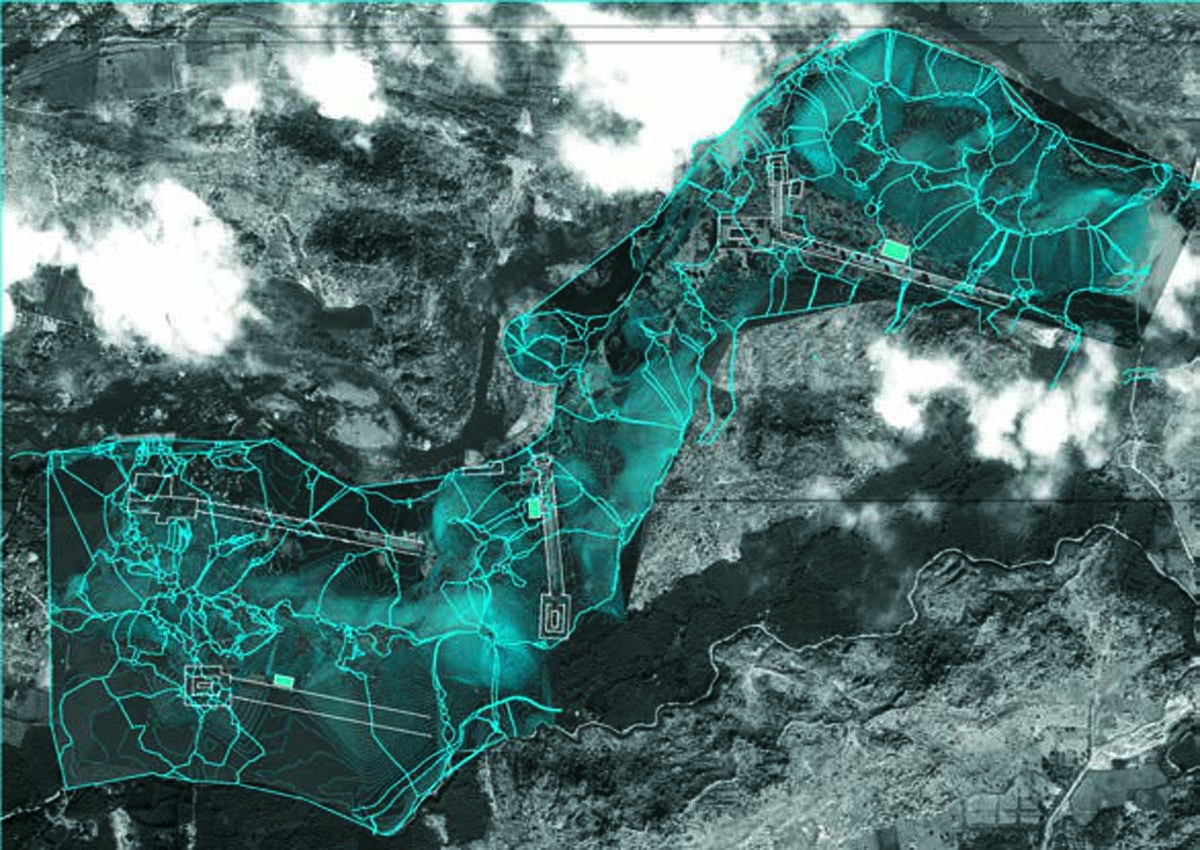

At its peak, Vijayanagara was the largest urban agglomeration of its day in the world, housing a population of over 600,000. Contrary to the prevailing trends of the period, Vijayanagara was not a uni-centered capital city. It was intentionally developed as a multi-polar urban settlement, where each settlement – or pura (‘town’) – had a centrality of its own. Each settlement was defined and dominated by a temple complex dedicated to the presiding deity and a large bazaar street axial to the temple. All other components of the town – housing, workspace and markets – stretched along and behind the axial bazaar.

Vijayanagara is strongly identified with the river Tungabhadra, one of the larger river systems of peninsular India. Earlier and later citadels the river’s edge.

The point of interest is the fact that the city did not use the river as a source for its domestic water needs.

This is exceptional and in fact quite counter-intuitive in a region that receives a mere 560 mm of rainfall annually. Barring irrigational requirements, the river remained untouched as a source of water.

While there is an immense volume of scholarship devoted to the grandeur of the ruins and the individual monuments of the Vijayanagara Empire, little is understood of the city’s nestled relationship to its immediate landscape as the main driver of its resource network. Most of the scholarly and professional work in the realm of landscape conservation in India has been carried out in and around individual historic buildings; usually in the form of palaces, churches and temples but invariably driven more by architectural rather than natural frameworks.

The rocky landscape of the region is characterised by a series of steep hills and valleys. The visual quality of the landscape is stunning with large boulders dominating the frame but with very few obvious signs of human intervention. The multiple nodes nestling in the valleys are visually isolated from the larger fabric. This distinctive settlement pattern has been traditionally interpreted as a security need – a marital response with the surrounding hills forming a protective enclosure. A closer examination reveals an intimate relationship between the settlement pattern and watershed characteristics of the terrain.

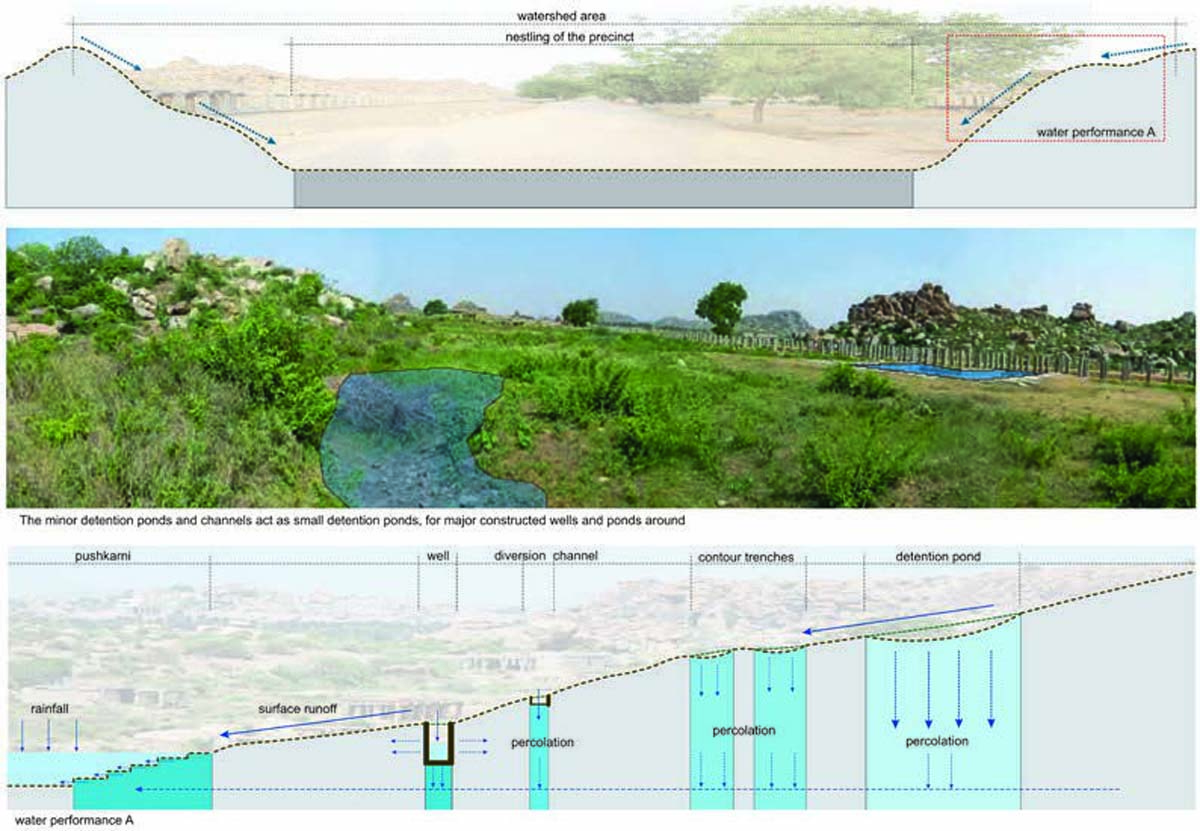

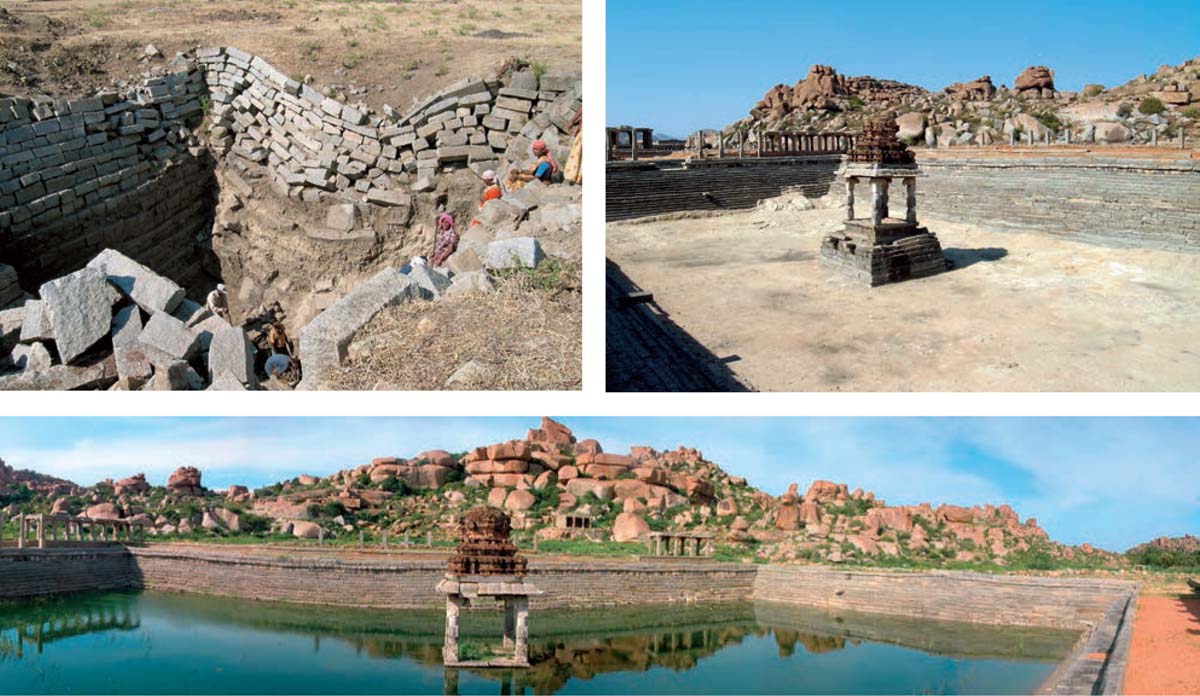

The main thrust of the conservation programme was the revival of the Pushkarani, the ritual stepped-tank along the bazaar axis of Vitthalapura. This was critical since the population of the day depended mainly on effective management of rainwater including harvesting, routing and storage. The series of wells and tanks extant in the landscape certainly of the city straddle either side of the river, with numerous religious and secular complexes dotting served more than a ceremonial function. With this background, once the physical restoration of the tank was completed, the rejuvenation of the water system was addressed.

Exploratory excavations in the surrounding hillside revealed several detention ponds and trench channels, silted over with time. These were restored to activate the water systems. It is seen that these embedded structures had been designed and placed in a manner that channelize surface run-o through a system of infiltration, percolation and recharge; ultimately leading the water to the Pushkarani.

After only one season, the Pushkarani was seen to hold water throughout the year in an area that is perpetually drought prone.

The critical issue that underpinned the entire process of site interpretation and landscape conservation is natural resource management.

Seemingly contradictory issues for preservation of the physical environment, preservation of the cultural and visual landscape and restoration of the authentic setting of the site needed to be addressed in an equitable and balanced manner.

However, once the deeper exploration of the site was undertaken, the contradictions resolved themselves almost seamlessly, to blend into a single, sustainable solution.

The model of water harvesting, management, supply and subsequent re-use directs the urban form towards a decentralised, multi-polar settlement pattern. Further, integration of the agricultural systems based on terrain and water needs can potentially create a pattern of development that effectively integrates the built and un-built. It also helps create immense diversity, rich in land use patterns and the visual landscape.

A deeper understanding of the conceptual framework of traditional landscape systems helps clarify the integral nature of sustainable settlement planning.

The learning from an ancient settlement can be judiciously applied in contemporary settings to address present day needs for a sustainable and equitable development. Cities can be more sustainable by modeling urban processes on ecological principles of form and function, by which natural ecosystems operate. The characteristics of ecosystems include diversity, adaptiveness, interconnectedness, resilience, regenerative capacity and symbiosis.

These characteristics can be incorporated in the development of strategies to make them more productive and regenerative, resulting in ecological, social and economic benefits.

Top right: Pushkarani after conservation - (Dec 2003)

Bottom: Panoramic shots of Pushkarani

The learnings from Vijayanagara demonstrate the immense depth of understanding and engagement with the larger landscape systems by the original builders. Rather than a problem-solving approach, the accent was focused on anticipation of solutions derived from nature-based models.

It is in this design process that traditional wisdom is seen to play a key role, having dealt with the same issues but with a greater reliance on natural systems. These are proven to be less energy-intensive, less stressful to the natural environment and more robust to the vagaries of climate. More importantly, such planning processes ensured equitable access to resources across social strata and geographies.

Strategic initiatives rooted in larger environmental issues can effectively reduce potential conflicts by addressing development issues in a manner that integrates the physical environment for its ecological services and is not seen as an impediment. Each aspect of the urban landscape can hence be defined, directed and formed by the interaction of the ecological framework set out on a larger scale. Active integration of watershed-related issues such as catchment protection, storage enhancement, storm water management, valley and streambed protection, aquifer recharge etc., will ensure long term sustainability of the development.

Increasing rates of urbanisation and decreasing access to critical resources like water and arable land, specifically in the context of the Indian sub-continent, demands an approach that should necessarily address urban and environmental issues differently and more effectively than present-day planning practices. Key parameters of the Vijayanagara urban systems – decentralised but dense urban settlements, nestled relationship to landscape systems, systemic integration of natural resource management within the urban fabric, complete water security, integration of livelihood and food security amongst others – retain their relevance even in contemporary settings.

Comments (0)