Smart: someone who is quick witted and intelligent; nimble and adaptable.

1985: TERRY GILLIAM’S BRAZIL = 2015: KOREA’S NEW SONGDO

As we look to the future of our cities 30 years from now, I am reminded of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, a disturbing, terrifying movie released 30 years ago, which represents a vision of the future city set in a centralized ‘big brother’ society. The city in Brazil is characterized by soul-less concrete skyscrapers and buildings connected to one another by a network of ducts for carrying and collecting information (in the form of paper), a concretized landscape devoid of any green, a city run by a ‘Ministry of Information’ and a world in which any nail that sticks out is hammered in. The culture of this society is one where there is a ruthless collection of information and omnipresent surveillance, zero value to individual human life and repetition and conformity are preferred over diversity.

From a technological perspective, Terry’s city ticks all the boxes for the ‘Smart City’ rhetoric of today. Our current vision of the smart city of the future as promoted by the larger IT companies and networks is one which unifies data collection through an army of sensors to automate routine city processes and enable centralized decision-making for greater efficiencies and cost saving. The difference is that today’s smart city discourse relies on sensors feeding into fibre optic cables carrying invisible data; whilst the city in Brazil has the omnipresent ducts carrying paper for information control. This myopic vision of a smart city raises concerns about individual liberty, privacy and of creating sameness in our urban landscape, topics prophetically covered in the film.

New Songdo in Korea is built on this premise of a smart city. Spread over 1500 acres, it focuses on business and innovation and is equipped with cutting edge Information and Communications Technology (ICT) underpinning its infrastructure. However, the city has been heavily criticized for its built fabric, mainly consisting of massive faceless housing blocks lacking character. New Songdo (reference #1 in footnote) represents the danger of using technology as a solution in a top-down approach creating sterile environments within an overly prescribed masterplan. Whilst an ICT infrastructure base for our cities is necessary and inevitable, the ‘Smart City’ rhetoric needs to go beyond that.

Open, Indeterminate and Adaptable

Innovation and development in cities happen in an unpredictable manner and often haphazardly.

Delhi’s uber-successful Hauz Khas village is a case in point where artists and fashion designers instigated the creation of a vibrant urban quarter full of cafes, bookshops and designer boutiques in a traditional urban village amongst the charpoys and cows. It’s totally unpredictable and beyond established norms. Similarly, the best developments, be it Camden Market in London or Chicago’s West Loop area, have come up by providing the right impetus or being at the wrong place at the right time.

Urbanization is inevitable. It is well accepted that cities are the future of humanity, the place where all of man’s creativity and innovation come together and offer the maximum economic opportunities. For a country of India’s size, our urban centers are sorely lacking and we have a lot of catching up to do. The government’s recent directive to build 100 smart cities is a small step in this direction. This raises an interesting dilemma, one of designing for India’s new smart cities but allowing them to be ‘un-designed’; indeterminate and open, complex and unpredictable with a sustainable footprint. The challenge is to harness technology appropriately to (re)develop ‘smart cities’ that will facilitate human interaction and collaborative innovation and offer its citizens a good quality of life.

ICT infrastructure is intrinsically a complex system and not too dissimilar to a city’s system. IW Berger (ex-Chairman of IBM Academy of Technology) states in his blog that the need of the day for the IT industry is the “use of platforms based on open standards, as well as an extensive industry ecosystem to generate complementary products and services” to allow a greater potential for innovation, growth and robustness (reference #2 in footnote).

Applying this thinking towards urban planning, the key is to develop smart cities that are centers of innovation by empowering and enabling citizens using technology to provide an open framework for development where citizens are encouraged to make the right choices.

The framework for any smart city discourse should cover three essentials: the city’s footprint, i.e., creating a development that is sustainable and ecological, the city’s mobility systems and the design of the city’s modules i.e., the urban fabric or building blocks of the development.

Smart Footprint

In the 20th century, the advent of the motor car allowed cities to spread into the countryside away from the traditional centers, which were compact, walkable with a dense self- shading urban fabric and a small ecological footprint. The low density, large footprint model has proven to be a huge burden on our environment and resources. Increasingly, studies have demonstrated that the ‘ideal’ city is one which has a tight-knit urban structure with high density and medium rise buildings with key services immediately accessible to all residents via a well-integrated public mobility system. This may be a single development or, in the case of megacities, a collection of micro- cities interconnected to one another by public transportation and digital technologies.

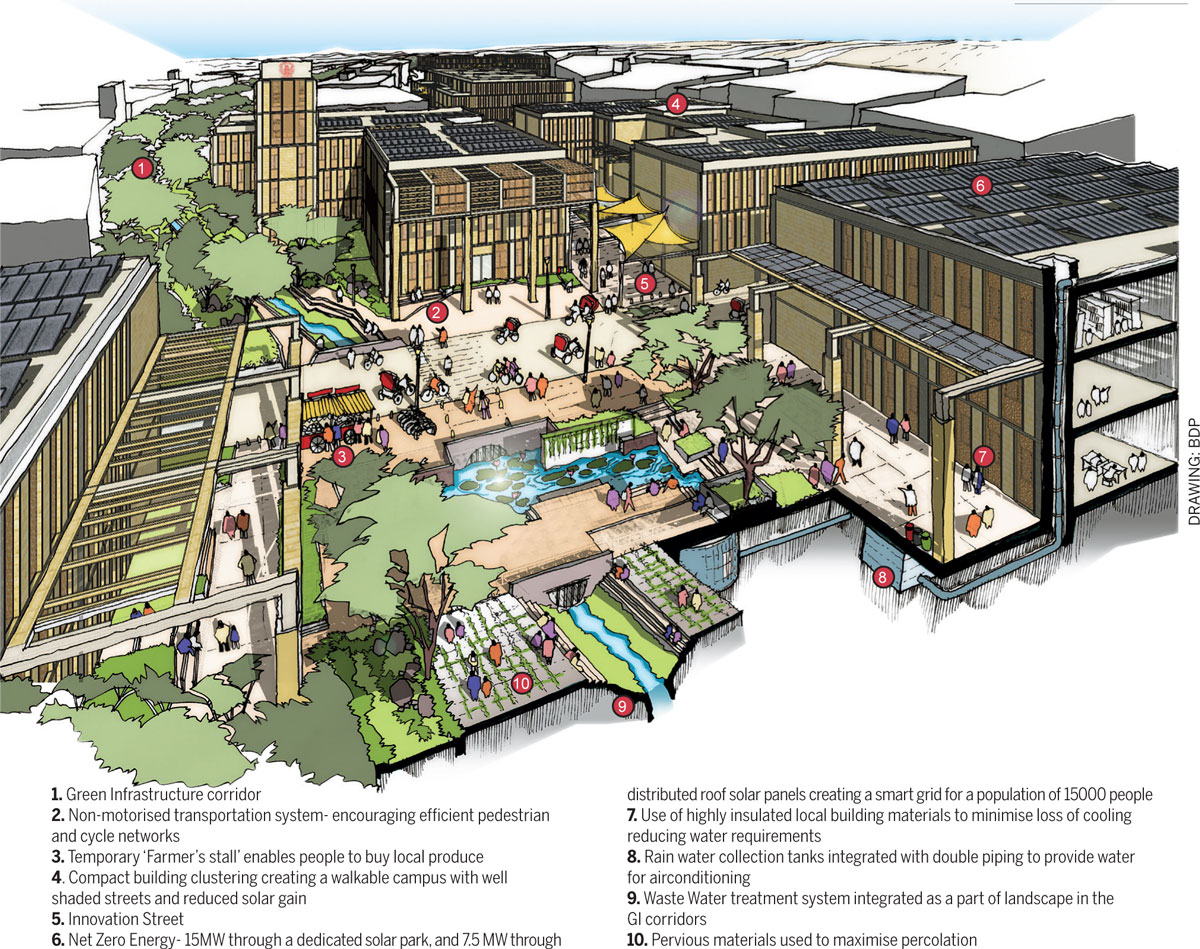

A smart development needs to have a Smart Footprint. As designers, this issue was foremost in our minds when master planning for 15,000 people for the new campus for IIT in Jodhpur. The site was spread over 800 acres and one of the early decisions was to create a compact walkable development in the center of the site and utilize the surrounding undeveloped land to help regenerate the ground water table, follow sustainable agriculture practices and for solar energy generation. The aim was to provide the campus with a masterplan that is not overly prescribed, but one that achieves sustainable place making by encouraging behavioral change – where the best choice given to the user is the sustainable choice.

The compact urban fabric allows for solar shading and combined with sustainable methods of construction, will give residents a choice not to use artificial cooling systems. The development integrates public transport options with pedestrian shaded walkways and residents will have a choice to walk, cycle or hail a battery-operated rickshaw. Water conservation strategies and recharge measures have been put in place, giving residents a choice to use the recycled water for irrigation, air conditioning and flushing. The masterplan for IIT Jodhpur relies heavily on technological innovations in construction practices and in energy generation to achieve near Net-Zero in its energy and resource consumption. Technology here has helped the development achieve a smart footprint.

Smart Mobility

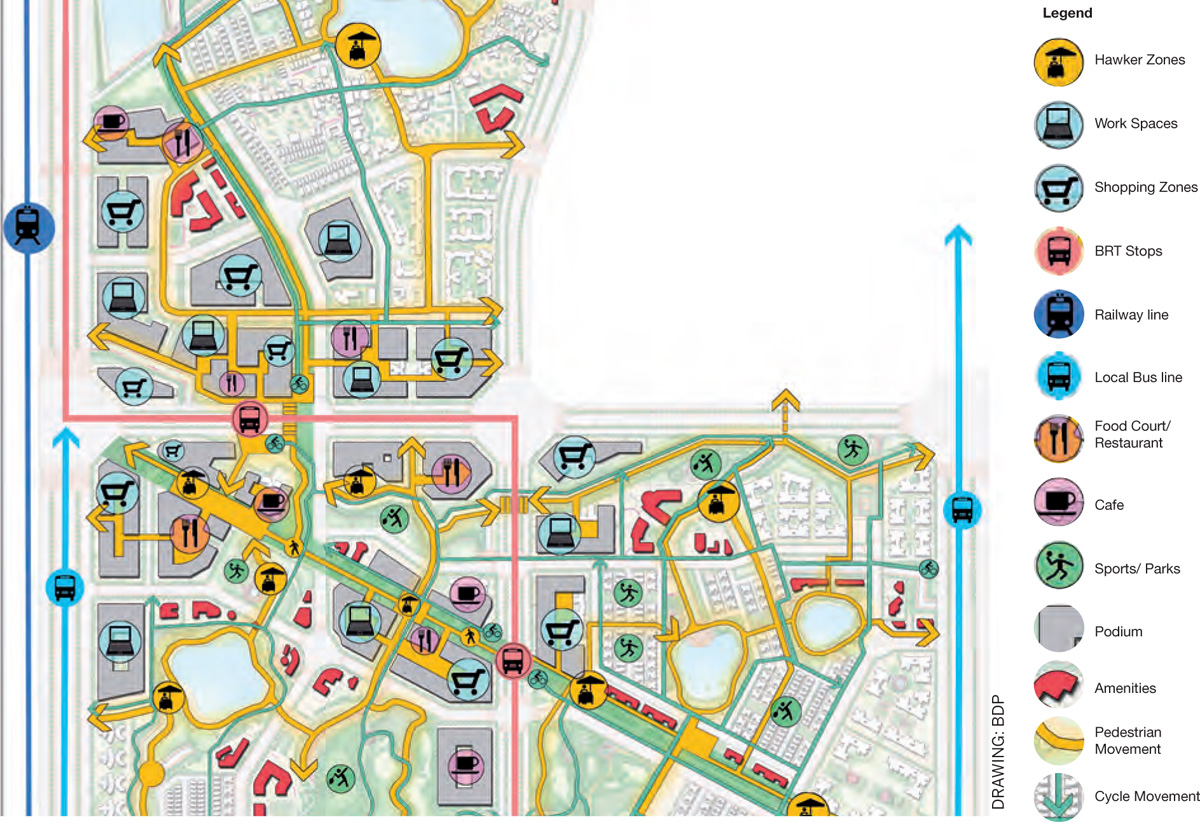

Such developments can further improve residents’ quality of life by adopting a well-integrated multi-modal sustainable transport system that improves access to a city’s services and reduces congestion. In India, ‘Transit Oriented Development’ (TOD) guidelines are now becoming the norm and are being woven into the local authority’s development plans. This was part of the brief for a masterplan for three residential sectors in the new capital city of Naya Raipur. Proposed new development surrounding the Rapid Bus corridor (BRT) is designed to be compact, high density and mixed use. There are clearly - defined pedestrian and cycling routes between blocks with active ground floor uses and various zones for retail, play and leisure along the streetscape. The masterplan provides a wider choice of mobility to users promoting the use of non-motorized vehicles and well - connected pedestrian and cycle networks, overall providing safety, better health and quality of life.

The key to any new development for an existing city to achieving Smart Mobility is to ensure seamless movement between one means of transport to another. The failure of the Delhi BRT has often been blamed for the lack of last mile connectivity and of not integrating the BRT with the metro. What if the Delhi metro allowed you to carry your bicycle on board? Or if buses ran a special route for cyclists? Perhaps then such systems could flourish well in a city obsessed with the personal car. Delhi can take lessons from the Finnish capital of Helsinki, which has an ambitious plan to transform its existing public transport network into a comprehensive ‘mobility on demand’ system within 10 years, which could render individual car ownership useless. Subscribers will choose origin and destination points, Uber style, and pay in one go for reaching their destination via any number of modes such as driverless cars, rail-based systems, hired cycles, shared ferries and so on. Here, technology is being put to use in a visionary manner to enable the networked commuter to plug into the mesh of networked public transport options. (reference # 3 in footnote)

Smart Modules

The fast-accelerating economic cycles and unprecedented development in technology along with a rapidly increasing urban population has impacted the 20th century city that has so far coped with this volatile environment by displacing activities from one place to another. Tokyo and New York are prime examples where buildings were constantly torn down to make way for a newer, shinier product. This is interruptive and unsustainable.

Our cities need to be smart to adapt to the changing environment quickly and intelligently and allow its built fabric to be more accommodating and flexible.

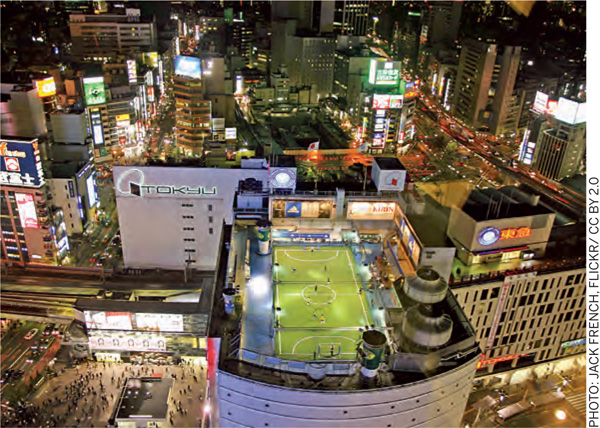

A smart city needs a wide variety of flexible spaces for working and living, of different sizes that can be rapidly re-purposed. In Asian cities, it is not unusual to find a flexible use of space to cater for high densities. There are examples of villa developments perched on top of a shopping mall, soccer fields on rooftops, using technology in the form of space-saving furniture and movable panels to transform small shoebox apartments for multiple uses and even a temple located on the roof of a private housing block. These examples are born of necessity. If technology could be used to design Smart Modules to be more accommodating and flexible, we would close the gap and allow our cities to be truly adaptable and smart.

|  |

Smart Modules are applicable across all levels – from the urban block, to the architecture of individual buildings, planning and insurance policies that allow flexible time- sharing of space to the relation between the built and the surrounding landscape.

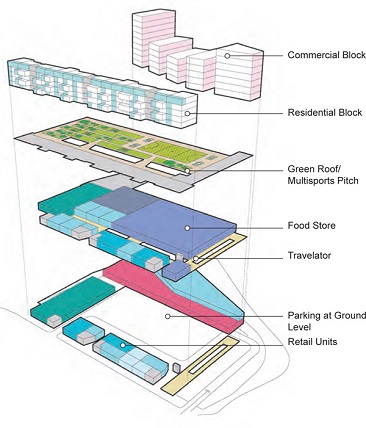

Urban Block: In Backaplan, Gothenburg, the masterplan for 5000 highly sustainable homes proposed adaptable urban blocks that could host a multitude of uses including live-work units, commercial units, a varied mix of apartment sizes along with rooftop green spaces and could easily accommodate changing housing requirements. This could allow the development to change and adapt to the vagaries in the market cycles with ease.

Mixed Use: Technological advancements offer designers so many possibilities to create Smart Modules that allow a true mixing of uses; whether it is housing perched on the roof of large format retail or a park over a hospital or urban farms in office buildings such as the Pasona Group headquarters in Tokyo where tomatoes dangle from ceilings, herbs grow on the walls of meeting rooms and a paddy field is the office centerpiece. BDP’s Chavasse Park at Liverpool One demonstrates an innovative approach to the provision of open space in the heart of Liverpool’s retail district by placing a two-hectare park above four levels of a new city centre car park.

Modular and Adaptable: At the building level, technology can allow configuration for multiple uses within the same space. BDP’s design for ABITO is an innovative ‘micro-flexible’ module for live-work in just 350 sq ft. The apartment has at its heart a central pod that divides the space into two – the first, an area for sleeping or working with a folding bed and a folding work station and the second, an area for living with a floor-to-ceiling window. The central pod itself is prefabricated and is an innovative feat of technology and contains a bathroom with a shower, a compact kitchen with dishwasher, fridge, oven with hob and cupboards, a utility room with boiler, washer, dryer and the fourth side facing the sleeping space with wardrobes, drawers and other storage. The Abito model is scalable and the developers have used it to create a multitude of housing blocks.

Photo: Wikimedia/ CC SA -3.0 |  Photo: BDP |  Photo: © Martine H. Knight for BDP |

Drawing: BDP | ||

Techno-Able

In all the above-cited examples, technology has been an enabler of truly fantastic and innovative developments. My premise is that the ideal smart city should harness technology intelligently to embrace complexity and allow creativity to flourish, to be environmentally sustainable, well connected and to be designed to be flexible and adaptable. This is a lot to ask of a brand-new city.

A Google search of ‘Top 10 Smart Cities’ will list out established cities such as London, Barcelona and Toronto. These are all successful cities with a long history and to expect new cities and developments to overnight metamorphose into Smart Cities is unrealistic. This is in part because successful cities are a function of mature social, economic and political processes, which form the urban dynamic.

Whilst we have the technological expertise to build environmentally and technologically ‘smart cities’, at best these can only provide the platform for success; it is what we as humans do with this platform that will determine how successful and smart these cities really are.

For this reason, there is a lot of merit in developing Smart Cities as extensions or closely connected satellites to existing cities, to take advantage of the depth of social and economic infrastructure and opportunity that is already present, to provide the new-born smart city with the right support to enable sustainable growth. The parent-child relationship may well be an appropriate metaphor for the development of new smart cities in India that can grow up to be adaptable, smart and wise.

1. ‘No one likes a city that’s too smart- Richard Sennett’ http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/dec/04/smart-city-rio-songdo-masdar

2. http://www.irvingwb.com/

3. ‘Helsinki’s ambitious plan to make car ownership pointless in 10 years -Adam Greenfield’ http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/jul/10/helsinki-sharedpublic-transport-plan-car-ownership-pointless

Comments (0)