Once seen as a distant possibility, climate change is now a hard-hitting reality. Millions of people are being forced out of their homes by the aftermath of climate change, creating one of the biggest refugee crises the world has ever seen. In the coming decade, this number is expected to dwarf current statistics of conflict-ridden migrants. Such an upheaval will precipitate unprecedented challenges particularly for developing nations that are least prepared to withstand the effects of climate change. Many displaced populations remain in their own countries (Internally Displaced People or IDP) and this number is high. As per the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, in 2016, 2.4 million people were displaced internally due to disasters in India accounting for two-thirds of the total 3.6 million IDPs in South Asia. Despite its global scale, the issue of internal displacement remains largely overshadowed particularly with the current global focus and public attention on refugees and migrants. As increasing global temperatures, rising sea levels, changing seasonal patterns, droughts and floods become frequent occurrences and the adverse effects of climate change worsen, we are likely to see more migration as people leave their countries for better security, resettlement and livelihood options elsewhere. Thus, today’s IDPs are likely to become tomorrow’s refugees unless an immediate and coherent response is provided.

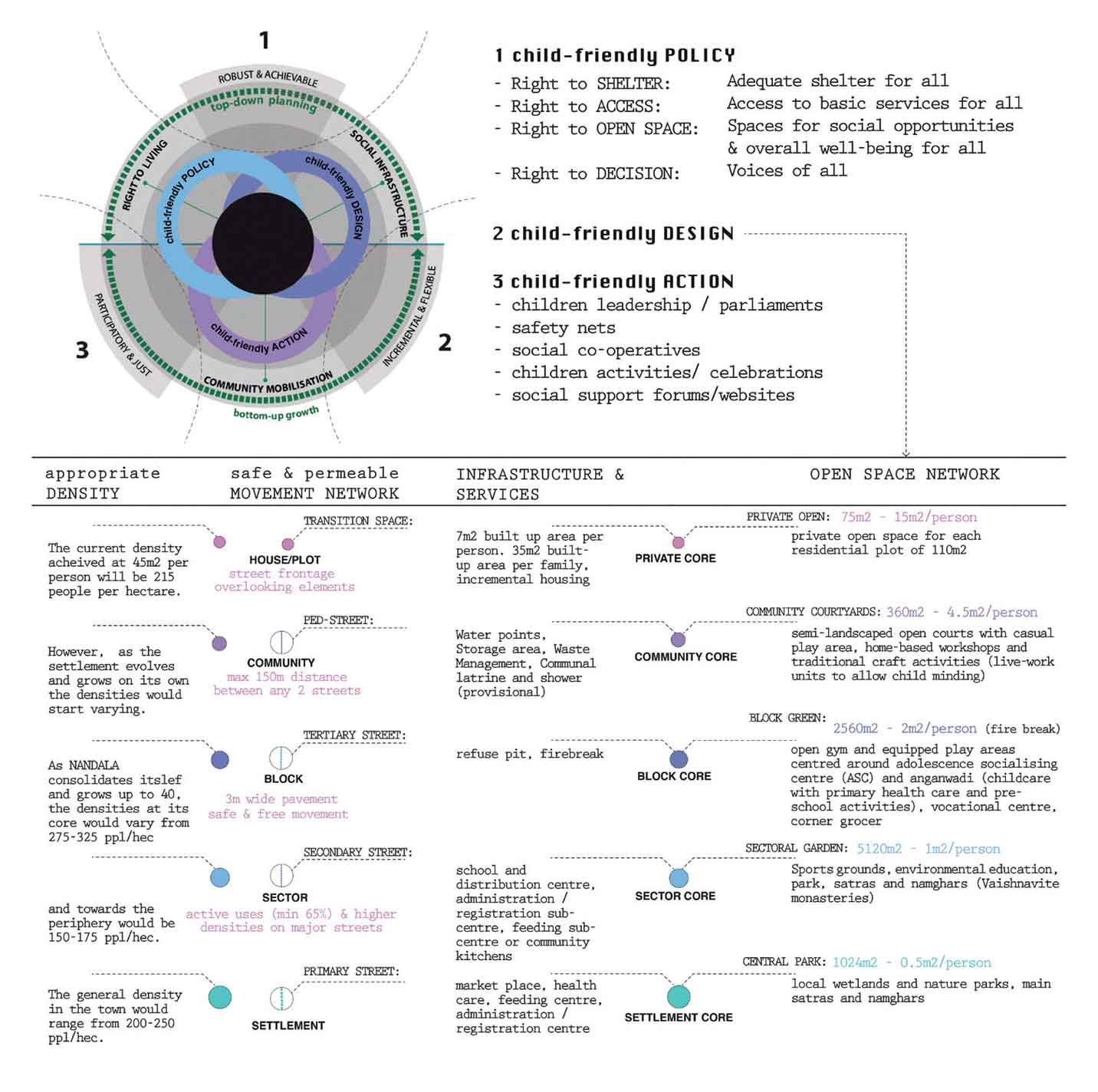

Evidence also shows that amongst the IDP, children and adolescents are the most affected in the aftermath of any disaster or conflict situation, having a negative impact on their overall well-being. The displacement away from their home environment, exacerbated by poor living conditions in relief camps, insufficient access to healthcare, sanitation, education, psycho-social support and other safety nets makes children the most vulnerable, yet they are a demographic group that is often ignored in settlement design. Child-friendly approaches to policy, design and action not only make a huge difference to children’s well being by giving them a sense of safety and normalcy, but also eliminate their exposure to abuse and trafficking that is prevalent in the aftermath of any natural disaster. Both hard and soft child-centric infrastructure in a refugee settlement enables them to cross from the emergency to recovery phases with minimum disruption. Thus, given the potential devastation associated with future climate change related disasters, it becomes inevitable for the designers and policy makers to actively engage in building sustainable, resilient communities. Moreover, decisions made now about the design, location and operation of social and physical infrastructure will determine how resilient they will be to a changing climate.

Decisions made now about the design, location and operation of social and physical infrastructure will determine how resilient they will be to a changing climate

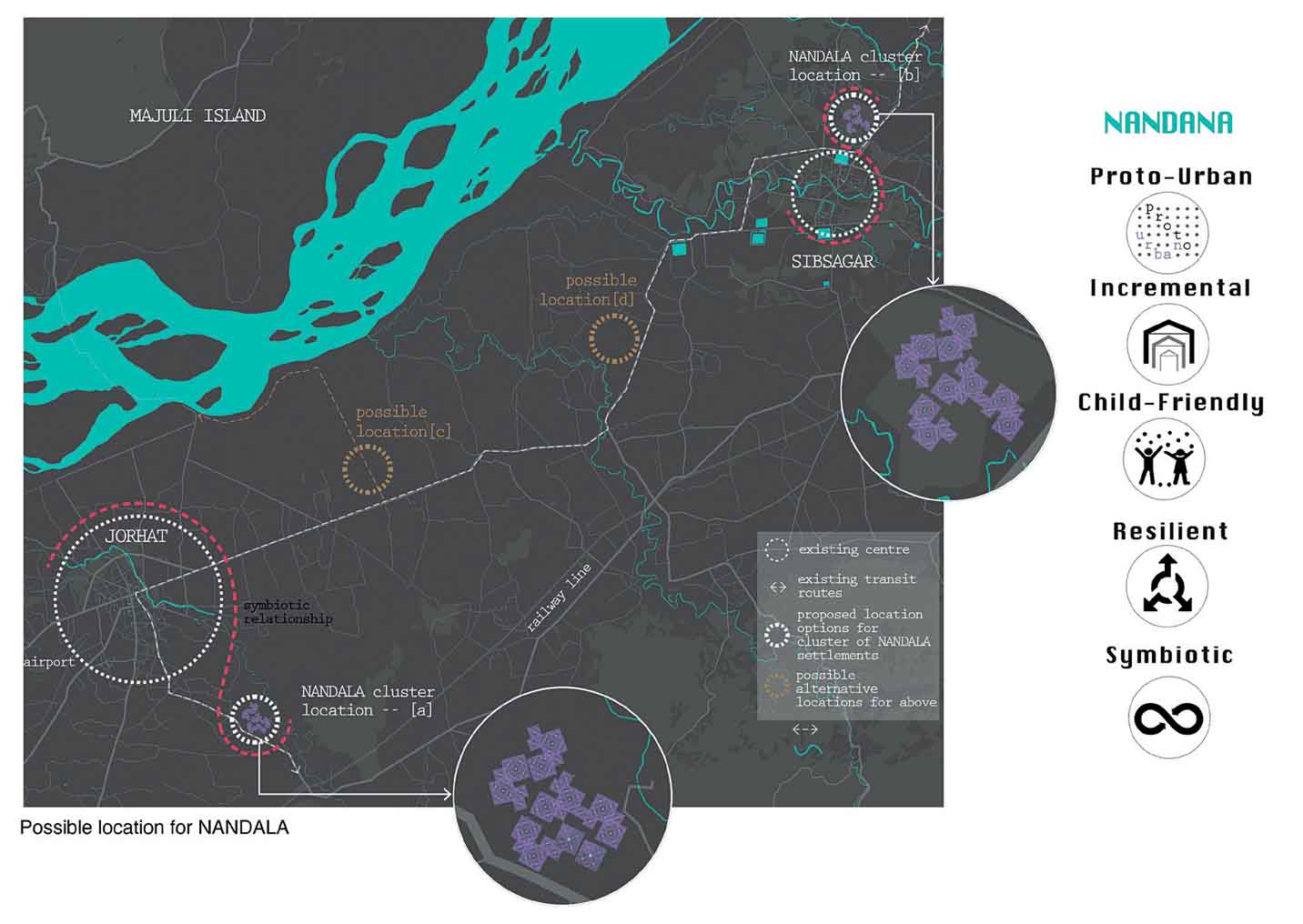

With this argument we propose the concept of Nandala, child-friendly settlements for the internally displaced people. Nandala, a Sanskrit word that means ‘child’ as well as ‘rejoice’, is contextualised to the island of Majuli located on the mighty Brahmaputra River in the state of Assam in North East India. Known for its natural and cultural diversity, Majuli is one of the largest inhabited riverine islands in the world and a seat for Neo-Vaishnavism culture, core to which are the monasteries or ‘satras’ from the 17th century. They continue to shape the lives of several indigenous inhabitants including their art, culture, traditions as well as natural environment. This unique island, however, is facing an existential crisis as extreme rainfall events and frequent floods in the mighty Brahmaputra are eroding Majuli at an alarming rate. The island, which once covered an area of 1250 sq. km., has been losing its land to erosion and measured around 733 sq. km. in 1914. With further reduction it measured down to 518 sq. km. by 2009. The shrinkage along with increasing population density is putting immense pressure on the area’s forest reserves and adversely affecting its ecosystems. This is not only devastating the island but also destroying its heritage and cultural traditions. The loss of 79% of arable land and flood situations have forced many people to move off the island to IDP camps, sometimes also to squatter settlements in capital cities within the country, but they largely remain agricultural labourers.

2. Chang Ghar (traditional houses on stilts)

3. Traditional mask making

Efforts are being made to cater to increasing flooding events and river bank erosion through introduction of smart flood forecasting technologies. There is also a proposal to create a fortified network of embankments in addition to the new Roll on-Roll off (Ro-Ro) facility to provide much needed connectivity for the island. Steps are being taken to make Majuli a carbon-neutral district by 2020 through introduction of emission reduction technologies and afforestation activities to combat residual emissions. These early-warning and protection strategies, however, may not prove to be enough to face the rising impact of climate change on the economic activities, food security, health, natural resources and physical infrastructure of Majuli. With its present geographical area reduced to half its original size, it is anticipated that Majuli will be lost forever in a short span of 20-30 years, permanently displacing its projected population of 188,672 by 2035. Such a scenario may displace people not just as IDPs but also as climate refugees. Therefore, plans for resettlement of its population to save them from the onslaught of increasing climatic impacts seems necessary. We thus propose the concept of Nandala satellite settlements.

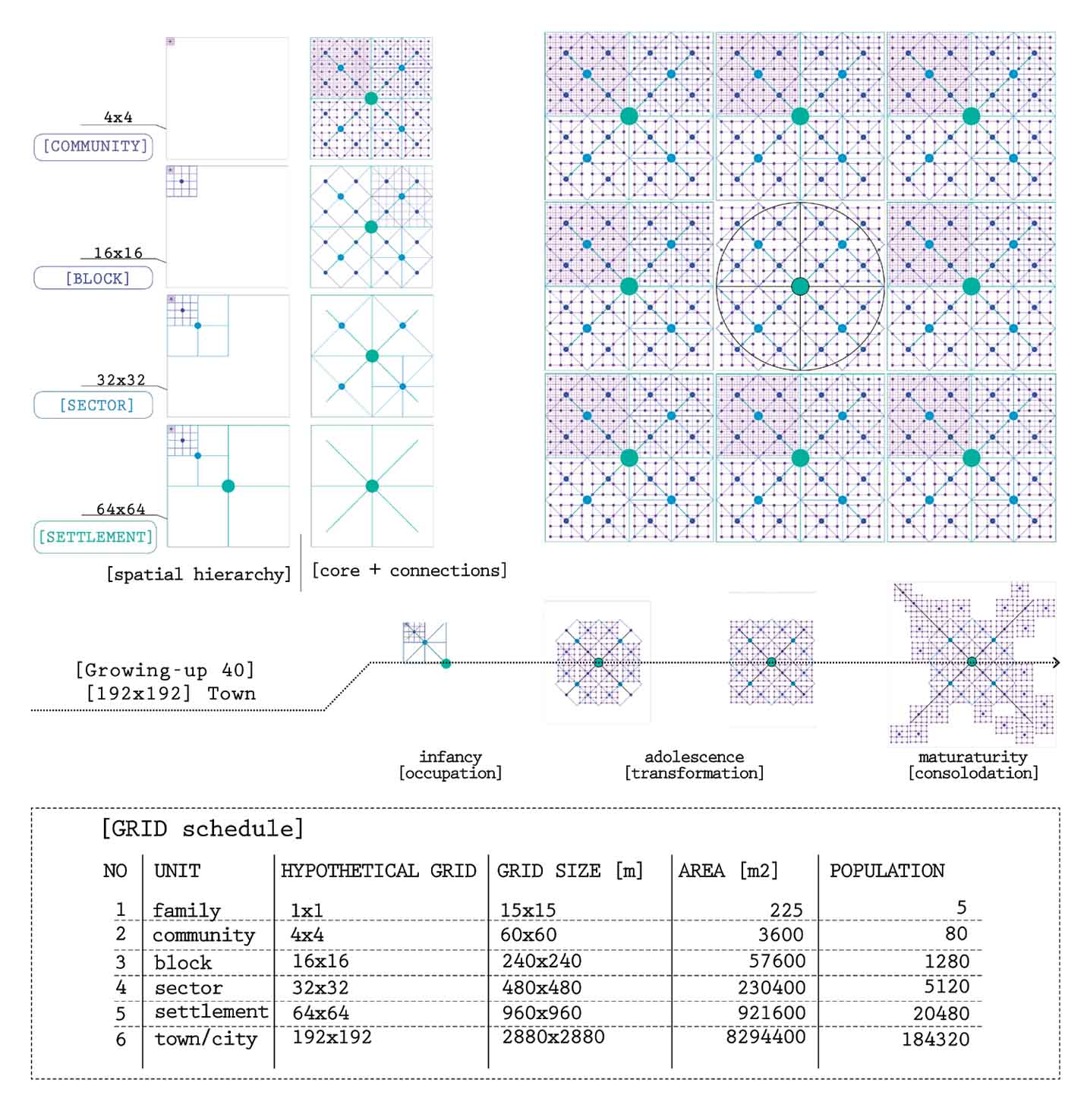

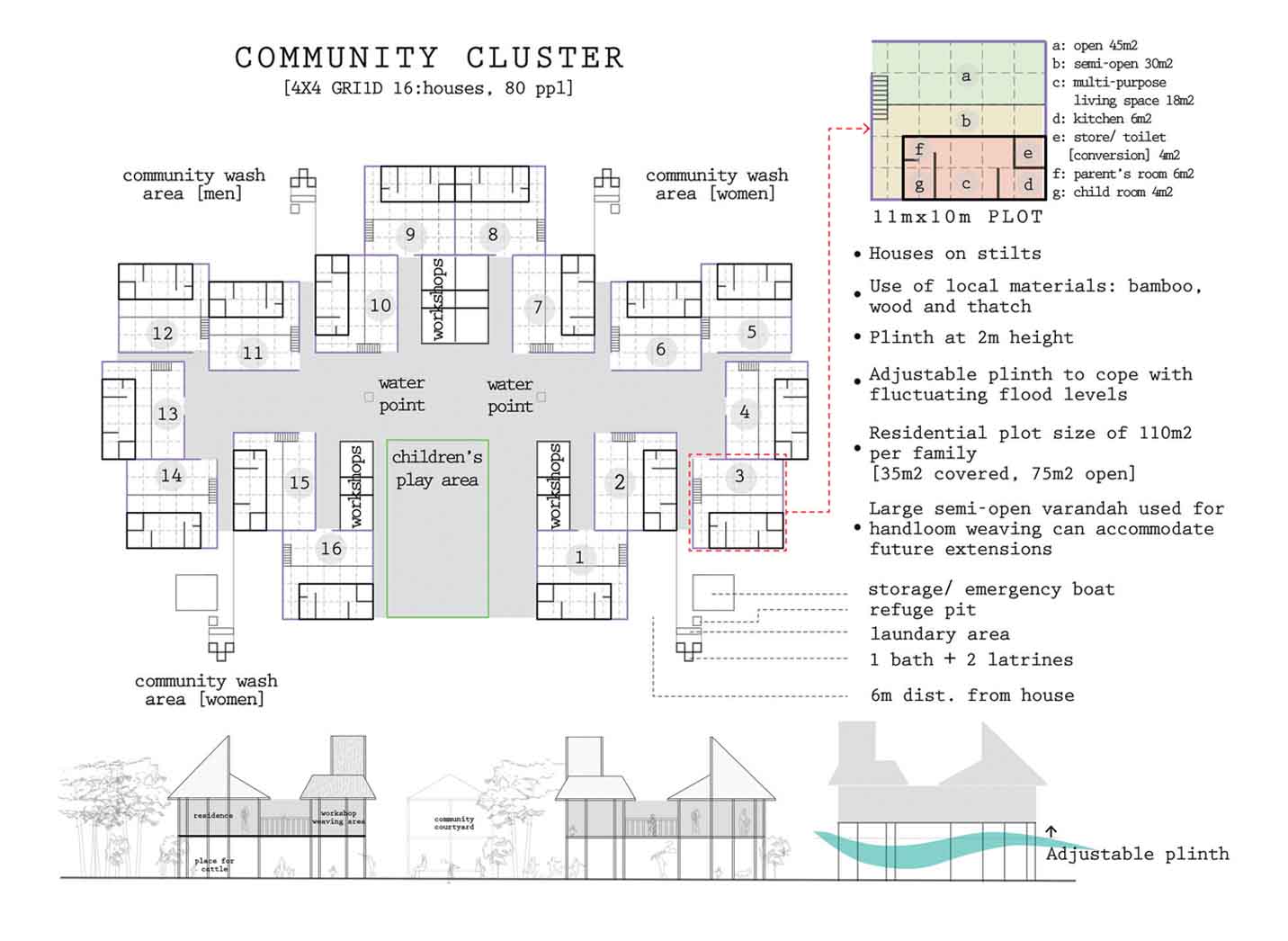

Settlements were built and continue to be built along water sources such as riverbanks and the seaside. Conceived as satellite settlements of about 1 km2 in size with a population of 2000, we propose that a cluster of nine such Nandalas be developed along the growth/transit corridors of existing historic cities (such as Jorhat, Sibsagar or Lakhimpur) on large government sites or land obtained through land-pooling [(1x9)km2 for a town of 1.8 lakh displaced population]. Proximity to the Brahmaputra is given due significance as the river is an integral part of the spirit of the inhabitants. Each Nandala is unique and versatile because it derives its resilience from a hypothetical living grid. It takes the smallest unit of 15mx15m [5 persons per family x 45m2 = 225m2] and creates a trellis1 with a series of design principles/guidelines. Instead of a site specific and rigid blueprint layout, this living grid will evolve: it multiplies, divides, expands or even shrinks when necessary, providing a flexible framework that constantly adapts to the unpredictable grounds of the mighty Brahmaputra. This process going from vulnerable to resilient is anticipated to take 40 years and can be applicable to refugee settlements worldwide.

The design of the settlement is based on five key principles:

1. Proto-Urban: We study the indigenous as well as informal settlements in Assam to understand their resilient design that sustain within the framework of a fragile ecosystem. We also draw parallels between their processes of growth from occupation to consolidation and argue that they can be seen as the first stage in the emergence of a town/city.

2. Incremental: We propose incremental housing and conceive the growth of the settlement through its four life stages viz. from birth up to 40 years: 1. Occupation (birth), 2. Appropriation (infancy), 3. Transformation (adolescence) and 4. Consolidation (maturity)2. Having reached this stage in 40 years we argue that Nandala will continue to evolve like any other town. With early provision of child-friendly resilient infrastructure, both social and physical, it will function efficiently for many more years.

3. Child-friendly: The child-friendly policy, design and action plans for Nandala establish a strong relationship between the built environment and child health and development. Details are represented in the accompanying diagrams.

|

|

4. Resilient: We develop a flexible design trellis or living grid that provides a resilient framework for the growth of the settlement. Nandala leaves more room for the water through its network of open spaces in the form of private open, community courtyards, block and sectoral greens as well as the central park. This network holds back the water runoff and reduces the risk of flooding. The raised housing clusters designed in consideration with the native typologies, orient in the direction of the river Brahmaputra allowing more rapid evacuation of the water in the event of floods. By giving way to water rather than resisting it, the housing on bamboo stilts further preserves the water runoff capacities beneath buildings. The indigenous people of the island will bring with them their traditional know-how and skills in context to living in harmony with the mighty Brahmaputra.

Critical activities such as healthcare, schools and banks are located away from very high-risk zones and raised or tied to a safe elevation. While key transport infrastructure is designed as amphibious, traditional wooden boats are a key mode of inter-cluster transport during and after floods. Sand motors can act as a protective flood barrier allowing natural dune formation along the riverbank. In some cases, design and integration of flood protective structures with urban infrastructure such as super and multi-functional embankments can be provided. Emphasis is given to indigenous plantations such as the ones in Molai Forest of Majuli along the riverbank as well as around the housing clusters. Moreover, afforestation efforts in the upstream areas of the Brahmaputra to transform the now degraded regions into greener regions and socio-political strategies of circumventing shifting cultivation will also act as long term strategies to cater to increasing flooding events.

5. Symbiosis: Nandalas share a symbiotic and economic relationship with the mother city where the latter provides an economic toehold while the former diversifies and contributes to the economy of the mother city. The concept encourages mixed paddy cultivation (ahu-bao) and also promotes alternative livelihoods based on traditional arts and crafts such as mask, ink and paper making, weaving and bamboo crafts, folk dance, music and drama, as well as eco-forestry activities and biodiversity conservation adopting bio-engineering means, local community best practices and extensive afforestation techniques to combat the challenges of climate change. A unique combination of bottom-up actions and innovative top-down interventions will transform these settlements into respectable neighbourhoods over a relatively short period of time, such that they no longer remain liabilities and instead become wonderful catalysts of urban change.

All together, the efforts ensure that the day-to- day life of children and other residents of Nandala are not adversely affected by the aftermath of climate change and hence they do not have to relocate elsewhere.

References:

The concept of [1] masterplan ‘trellis’ upon which the vine of the city grows and

[2] The process of natural growth are applied from my forthcoming (2019) book co-authored with David Rudlin “CLIMAX CITY : Complexity of Urban Growth” by RIBA Publishing.

All photos: Author

Comments (0)