It is apparent that trees in many ways provide the most important solutions to our environmental challenges. Their preservation in dense urban environments and the use of natural wood in the construction of buildings are both important activities, which when done in a planned manner can provide sustained positive impact on the environment for generations.

According to recent estimates, the construction industry in the United States alone contributes between 35-41% of the total CO2 emissions in the environment. Other countries have reported similar numbers, thus making the construction industry the single largest emitter of CO2 gases in the world. It has become imperative in our times to conceive of a new development model with new methods of construction that are far less detrimental to our physical environment. The future of construction will have to be based on building methods and construction materials that will contribute towards long-term ecological sustainability rather than short-term economical gains alone.

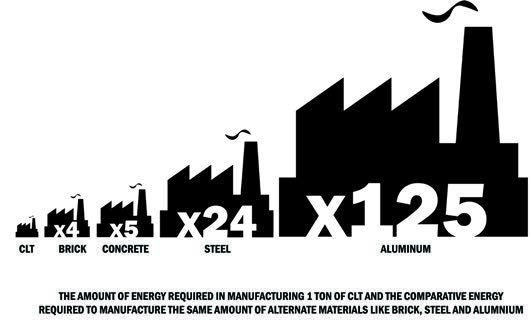

Apart from some distinct advantages of using steel and concrete as a response to the current construction cycles, the excessive use of these non-renewable materials has had a huge impact on the environment. For example, most primary construction materials require tremendous amounts of energy during their formation. The diagram below gives a comparison of this.

On the other hand, natural wood has undergone considerable development in its engineering, making it fully adaptable to contemporary construction challenges and demands.

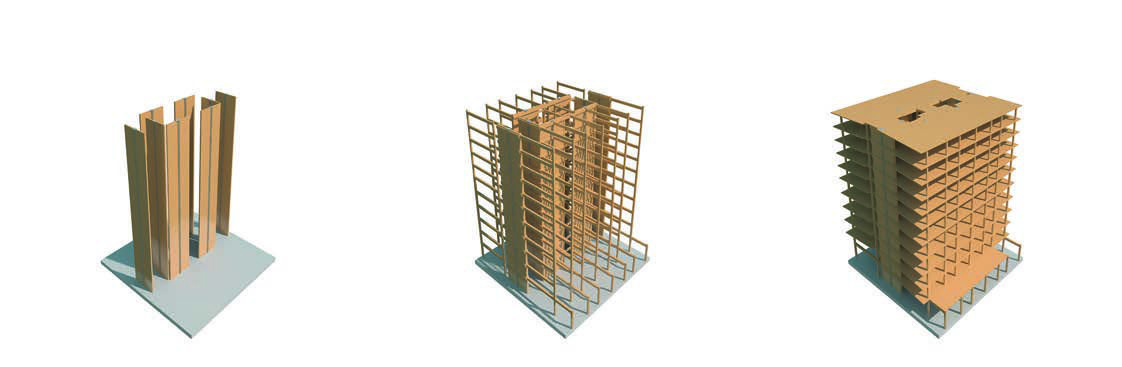

One such experiment to evolve a new wood-based material was carried out in the early 1990s in Austria, which resulted in the development of an engineered wood material known as mass timber or Cross Laminated Timber (CLT). CLT in many ways is a comprehensive response to the environmental challenges posed by the excessive use of steel and concrete in the construction industry.

|  |

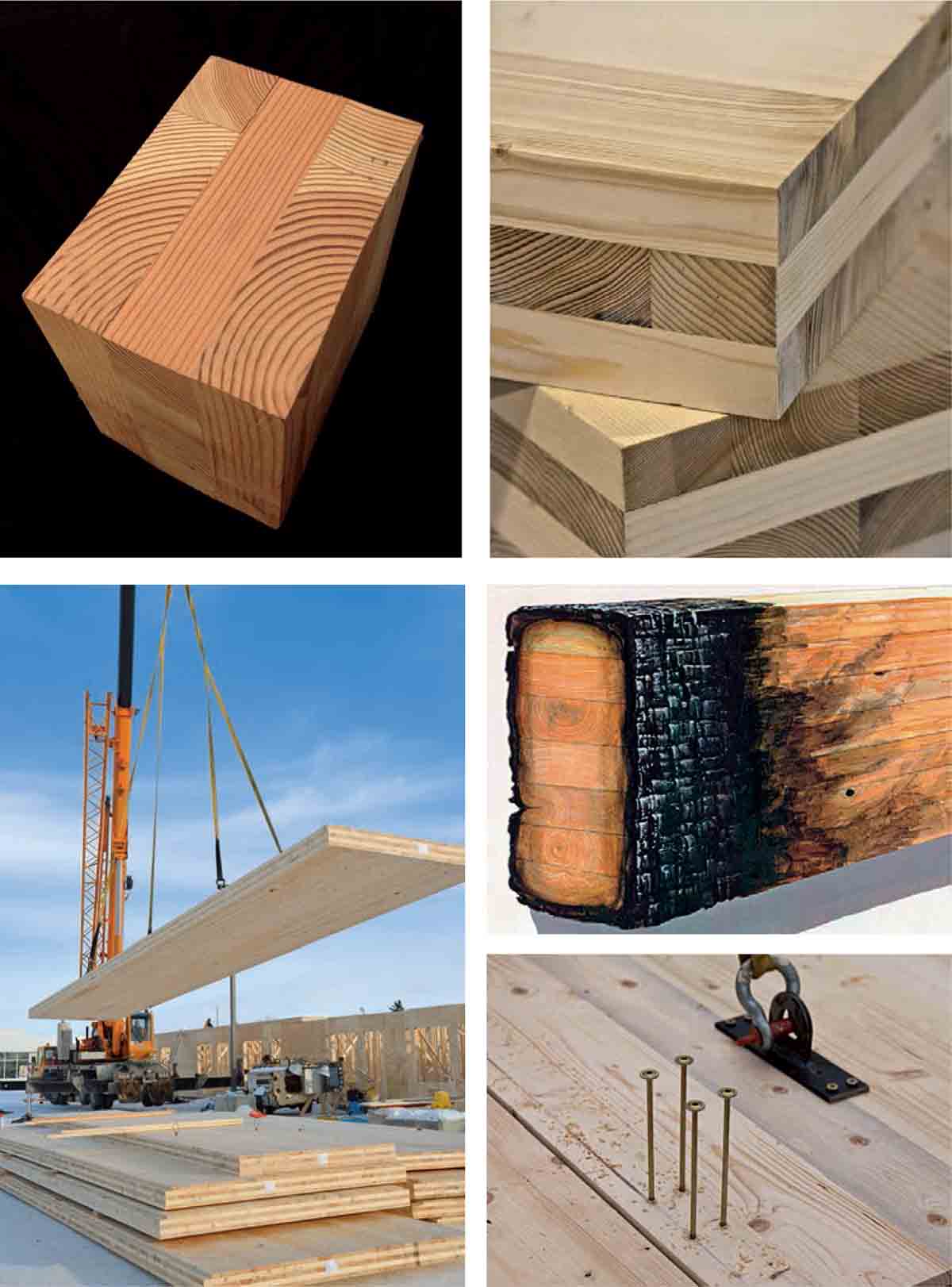

Traditionally wood is an isotropic material: it is strong in one direction (along its grains) but weak in the other direction. The design and manufacturing technique of CLT provides strength to the material in both directions thus overcoming this limitation of wood. It is made by aligning beams of wood side-by-side and in layers. Each layer is laid perpendicular to the one beneath it. A thin layer of glue is placed between each layer and usually 5-7 such layers are sandwiched together to form a board. These wood boards are then placed in a massive press, which squeezes them together. If longer sections are required, serrated interlocking holds them together. They are then glued to the matching end of the other panel to create sections up to 78-feet long. The boards can be custom cut to incorporate openings for windows and utilities as per the architect’s drawings. This process of manufacturing has provided wood, and CLT in particular, the advantage of reentering the construction industry as a principal building material offering comprehensive utilisation as various building components.

Bottom Left: CLT boards on construction site

Middle Right: Charred CLT

Bottom Right: CLT connection method

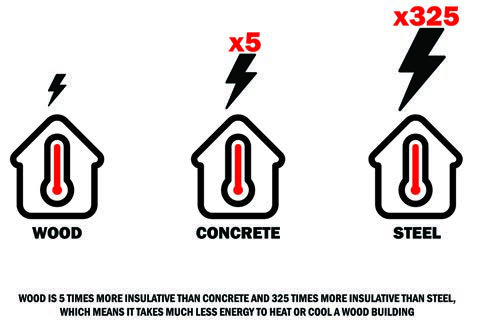

This recent advancement in wood technology coupled with growing realisations of energy consumption in the manufacturing of steel, concrete and aluminum for construction has provided an immense interest in wood construction. Compared to steel and concrete, wood is cheaper and easier to work with and can be assembled fairly quickly. It is more fire resistant than steel or concrete, because of the way wood chars. It is also the most sustainable of materials as it acts as a carbon sink: sequestering the carbon dioxide absorbed during growth even after it has been converted into lumber. This means the use of wood is an important answer to arrest the growing carbon footprint of the building industry.

The more wooden buildings we build the more carbon sinks we create.

But the way to perceive a sustainable solution is not as much to replace the dominant construction system but to find the opportunity for the use of wood as an alternate construction system. This is because with all the advances in wood engineering it still cannot replace steel and concrete as the preferred mode of construction for super tall towers (an ever increasing urban typology). However, the future of cities with re-densifying urban environments will still be dominated by mid-rise and low-rise development and here lies the tremendous opportunity for wood. If, in the western world, wood can be adopted to service this segment then the desired positive impact on the climate can be achieved.

But to do that, some fundamental misconceptions about wood construction and CLT have to be dismissed:

1) For instance, the first reaction to the use of wood is that it is easy to burn and self-destructs itself in a fire. But the reverse is true. Research and testing have shown that CLT provides excellent fire resistance. This is because mass timber is very hard to light, and once lit it wants to put itself out and this is achieved by the process of charring, the core of the wood member remains intact thus providing excellent structural integrity even when subjected to fire.

2) The second misconception is that CLT requires a high level of construction expertise. On the contrary, this technology is modeled on previous wood technology and therefore is easy to handle and assemble with a conventional wood installation crew. Most CLT panels are based on simple screw down connections and, with a manufacturer-provided installation plan, are suited for rapid project completion.

3) The third fallacy is that using wood for construction is not good for the environment because many trees need to be cut down to create the building material. This is not true since most CLT panels around the world are manufactured as 2X6 lumber from sustainably managed forests and most of the panels are manufactured using Mountain Pine trees that have been killed due to beetle attacks.

If these trees are not used they decay and emit carbon back into the atmosphere. Also, wood is the only primary construction material that is entirely renewable and therefore all the consumption can be replanted in order to maintain the overall inventory of trees on the planet.

4) The fourth misconception is that using wood and CLT is more expensive. This is false on multiple counts. It is a cost competitive building material that has tremendous long-term savings. It is 50% cheaper to install, because of the simplicity of joinery connections and prefabrication capability thus making projects open for business months ahead of schedule. Since the building structure weighs half the weight of conventional building systems the foundation cost can be much less.

Below are a few successful case study projects proposed/executed in CLT:

|  |

| |

T3 Minneapolis, Michael Green Architects

This building is a comprehensive example of embracing the new green building phenomenon in North America and Canada. It is the first and largest commercial building incorporating new wood technology. Having utilised 3,600 cubic metres of wood in its structure it will sequester 3200 tonnes of carbon for the lifetime of the building. Because it has utilised new timber technology it was built faster than a conventional steel or concrete construction and was finished in 2.5 months at a rate of 9 days per floor. The majority of the NLT (Nail Laminated Timber) boards were made of lumber from trees killed by the mountain pine beetle.

Framework, Lever Architecture

This 90,000 sq. ft., 12-storeyed, mixed-use building has been designed as a sustainable response to the mid-rise building industry. When completed it will be amongst the tallest timber buildings in the United States. This project advances green and sustainable building strategies and integrates the development of rural and regional economies by its method of construction and choice of material.

The latest innovations in wood engineering allow for timber to be used in multi-storey and long span structures. By replacing steel and concrete with timber, our buildings and cities can become carbon sinks rather than just sources of CO2. This is important for the future of the building industry and the environment.

Comments (0)