Art is a space of visioning, expressing the authentic and exploring the utopian. Artists instigate actions or installations that surprise, transport, disturb and touch strangers in vulnerable places. Artists change public perception of forgotten spaces. Artists provoke dialogue about difficult issues. But is it time to rethink the role art can play in a city where resources have never been distributed equitably, where developers are favoured over communities, and where cars are favoured over people? Can art offer tools to help Los Angeles out of the urban crises we find ourselves in today?

A healthy city welcomes dialogue and cultivates creativity

Los Angeles is fragmented by freeways and channelised waterways. Segregation of race and class continues to be reinforced across many fronts. Sites for community interaction are few. But this has not stopped people from expressing themselves boldly. Graffiti, murals and street art have long been associated with Latinx culture in Los Angeles, but its impulse is universal. Graffiti and murals are assertions of ‘the right to occupy public space’. When creative people are not engaged by existing forums, they may instigate their own forum in the most visible of spaces. City-makers and planners might ask the artists, “How can we create urban spaces that openly welcome the expression of such creative potential?”

Tapping into sensory experience to make spaces that feed community life

“Artists,” James Rojas observes, “begin their inquiry through a sensory experience, which is how people experience the city.” Rojas contrasts the methods of artists to those of planners. “Art venues are designed to engage, transform and inspire the public by their nature. Public meetings, on the other hand, are frequently scheduled at awkward times, poorly attended, have a rigid agenda and do not promote creativity.” Rojas ‘Place It!’ participatory workshops adapt the methods of artists to engage community members in re-visioning their own communities. This process involves storytelling and use of tactile objects that tap into the associations and memories of community members: “Sensory experiences of place that maps, data and other typical planning tools miss.”

Some of Los Angeles’ most evocative public spaces were designed by Lawrence Halprin, whose designs for pedestrian-oriented spaces were informed by participatory workshop methods that evolved from avant-garde dance practices of the 1960s and ’70s and collaboration with his wife, dancer Anna Halprin. Following ‘scores’, workshop participants explored collective responses to built and natural spaces.

Skillful choreography of bodily experience is undoubtedly one reason Halprin landscapes feel so attuned to the psyche. Street life becomes a stage for collective and community life, reaching toward a democratic ideal of urban landscapes as places of participatory social action.

Some have accused the methods and projects Halprin is associated with of catering to the concerns of privileged classes. Yet, both Halprin’s and Rojas’ methods suggest how channeling users’ sensory experiences and associations into the design of urban landscapes can dignify and express the values and experience of users. Can urban landscapes that better accommodate community uses strengthen community values and feed civic engagement itself?

Artists have changed how cities see public works infrastructure

‘Percent for Art’ policies in numerous municipalities require one percent of large development projects to fund public art. Involving the artist in the early conceptual phases of large public works has resulted in numerous projects that change our understanding of the role urban infrastructure can play.

In the ’70s, the city of Seattle began including artists alongside architects and landscape architects in the conceptual stages of large construction projects. Artist participation was unprecedented and led to an occasionally chaotic process. But the results demonstrated that the inclusion of artists could turn an unpopular project into a successful place that was embraced by the community. This set the stage for more groundbreaking artist involvement in infrastructure, such as Phoenix’s 27th Avenue Solid Waste Management Facility in the 1990s, where artists took the lead in re-designing an entire waste processing plant, transforming it to allow the public to observe every stage of processing an entire city’s waste stream. The public works department supported the idea that making visible a process which is usually ‘out of sight, out of mind’, might change public attitudes toward the creation of waste.

Public art has pioneered the integration of storm water infrastructure with transformative experiences in the landscape.

Herbert Bayer’s Mill Creek Canyon Earthworks (1982) is a 2.5-acre landform, which reveals the rising and falling of moisture levels through wet and dry times. Lorna Jordan’s Waterworks Gardens (1990-96) is a series of storm water treatment pools set into a symbology-laden landscape. Waterworks Gardens was featured on the cover of Landscape Architecture magazine. These examples are both from the Seattle area.

Artworks can pioneer technical processes. What’s more, artists have demonstrated that public infrastructure can be a subject worthy of poetry and contemplation. Such ambitious concepts can be realised when there is a strong collaboration between artists, public art administrators, engineers and municipal staff.

Recruiting artists to develop out-of-the-box approaches to complex problems

How we design cities to accommodate a growing population will shape the spirit of our communities.

Through its Arts Commission, Los Angeles County has begun hiring artists as ‘creative strategists.’ Selected artists spend a year in residence with county staff to develop and implement ‘innovative approaches to social challenges’, which are apt to include community engagement as well as creative experiences in the community. Currently the participating county departments are: Mental Health, Parks and Recreation and Public Health.

The proposal to outsource visioning around our region’s challenges taps the aspirations of artists for large-scale change making. Yet, if artists are to rise to the role of making lasting change, they also need to transcend the limitations of prevailing art practices that have been influenced by the commercial art world, which incentivize the production of artistic entertainment designed for short attention spans. To serve communities, artists must understand the lived experiences of constituents and then cultivate allies who understand processes of institutional change. Moreover, they must be ambitious in their vision.

Letitia Fernandez Ivins, the public art professional who enabled the commissioning and creation of Del Aire Public Fruit Park, says: “We need artists who will take the lead in pushing boundaries, proposing work that will stretch our constituency’s vision of what artwork can be and do.”

James Rojas observes that planners and artists have traditionally played different roles in the public eye. Held to rigid expectations, planners tend to be risk averse: “The public likes to be tickled by artists, but not by planners!” Yet planners understand codes, economics and the mechanisms of systemic change. Collaboration between planners and artists would allow outsourcing risk to artists. Then the planners and municipalities might seek to leverage the most successful discoveries in their own practice.

Artists create spaces whose legal status allows unusual things to happen

The legal status particular to ‘art’ offers a space in which certain kinds of actions can legally be permissible that might not be possible otherwise. In this way, art may be a testing ground for unconventional approaches. Art’s legal status has been used to protect the public’s interest (or provoke contemplation).

In 2012, art collective Fallen Fruit and the Los Angeles County Arts Commission leveraged the legal status of ‘art’ to allow the planting of public fruit trees in the artwork, ‘Del Aire Public Fruit Park.’ Risk-averse government staff had been concerned that fruit trees in a public setting could create a liability, attracting vandals, pests or dropping slippery fruit. But when fruit trees were determined to be the very material of the artwork, the planting was permitted.

Fallen Fruit is no stranger to playing with the law. The collaborative has investigated the legality of who can pick fruit that overhangs sidewalk space (there is no clear rule). Making maps of fruit trees which may fairly be harvested by the public playfully exploits this ambiguity and asks the question, what feels most ethical and community-minded in this legal grey area?

Though he has not called it an artwork, artist and activist Steve Appleton bought several acres of land that happens to be situated inside the Los Angeles River itself. Appleton’s stewardship of this land and his intimate observation of its ecology contrasts to the grandiose scale of planning and investment that this stretch of the river has attracted. Appleton hopes his status as a landowner will allow him a stronger voice when proposed development threatens to impact his river property. Appleton’s purchase brings to mind Canadian artist Peter von Tiesenhausen’s use of the legal status of art to stymy the progress of oil pipeline developers. In the 1990s, the artist claimed copyright over his own 800-acre property, giving it the status of inviolable cultural property and turning any disturbance of it into copyright infringement. This forced pipeline developers to reroute their line around his property. Though this artwork originated as a protest against the aggressive tactics of developers, the declaration of land as an artwork is consistent with the artist’s environmentally-minded work.

Art is the origin of Los Angeles’ most dramatic infrastructure project in progress

The revitalisation of the Los Angeles River began as an outrageous declaration by poet Lewis MacAdams in the context of performance art. In those days, the river was a forgotten and derelict space, an ‘urban hell’ avoided by most. Cutting a fence to gain access, MacAdams and his fellow artists asked the river if they could speak for it within the human realm, and it did not answer. This was the start of Friends of the Los Angeles River.

Starting as a handful of artist-believers working to protect the river’s interests, Friends of the Los Angeles River (FoLAR) grew into a grassroots movement and then a robust nonprofit, in turn influencing the county, and then the city, to create Master Plans for the river. FoLAR has been central in catalysing the work of activists, artists, environmentalists, politicians, engineers, designers, scientists and other urban change makers around the river. Though the dream of Los Angeles River revitalisation has grown beyond the original performance artwork to become a lightning rod for private investment and more than one billion dollars of federal funding, and has provoked a county-wide debate about environmental and economic equity, MacAdams’ poetry about the river (he refers to it as ‘she’) continues to be invoked as a guiding vision.

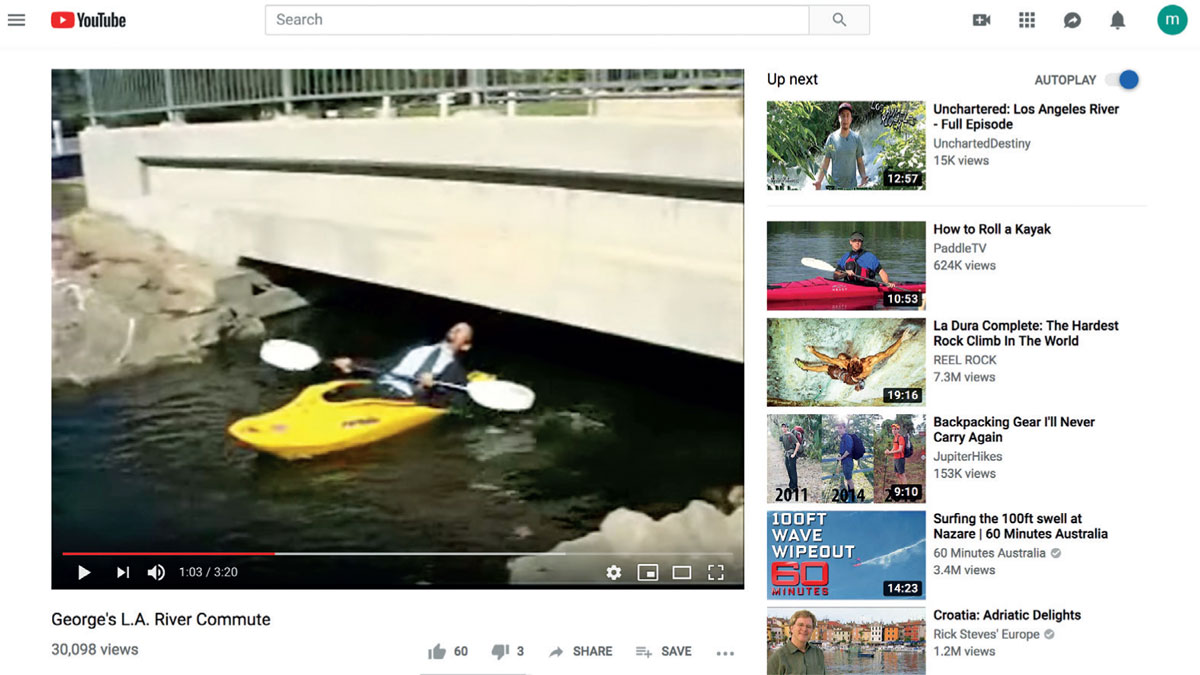

A second quixotic creative gesture played a role in securing legal protection for the Los Angeles River and its tributaries. A satirical YouTube performance shows a suited man kayaking in the Los Angeles River to avoid freeway congestion. Kayaker George Wolfe is the founder of LaLa Times (‘Everything Absurd Under the Sun!’). Heather Wylie, of the US Army Corps of Engineers, found his video when searching for any evidence one could boat down the Los Angeles River. Proving the river’s ‘navigability’ would make it eligible for federal water quality protections. Wylie and Wolfe organised a team to kayak the 51-mile river over three long days, documenting the entire feat on film. Not only did the team successfully ensure the entire river and its tributaries would be eligible for protection, but they changed public perception of the river.

Can the arts help cultivate equity along the Lower Los Angeles River?

The municipalities of Southeast Los Angeles (SELA) along the Lower Los Angeles River are exposed to high rates of environmental pollution and related health risks. Due to systemic racism over the last century, blacks, Latinx, and Asians could only buy housing in areas like SELA, which happened to be adjacent to areas zoned for industry where white people did not want to live. The communities of SELA have been subjected to, rather than active participants in, decisions made by planners.

Today, in SELA, the arts are being recognized for their power in cultivating public engagement. Local voices must be encouraged and local participation must occur if river revitalization can be successful. To encourage constituents to visit the river channel and to see how a revitalised river might bring communities together, Anthony Rendon’s office has sponsored an arts festival celebrating the culture of SELA. Rendon, Speaker of the California State Assembly, introduced the bill that resulted in the creation of the Lower Los Angeles River Revitalisation Plan.

The SELA arts festival showcases local music, art, poetry readings, community theatre, graffiti art, artisans, folklore and food. Rendon says, “For folks in this community to have an art event of their own making in their own community, that’s what this event is about.” All this is deliberately situated within the vast river channel itself, a starting place for community visioning.

Los Angeles needs radical creative visioning

Los Angeles is in the midst of a crisis. The region’s rivers, sidewalks and alleys are filled with people who cannot afford housing. Regional policies intended to create sustainable cities, by increasing density around public transit centres, also threaten to displace long term residents. Renters are especially vulnerable to displacement, making up 80% of the population of some municipalities. In South Los Angeles, 45% of 800 residents surveyed believed they would be forced to move within the next five years due to the impact of development in their own neighbourhoods. Artist and activist John Urquiza, who works on raising awareness and resisting displacement in communities states, “What communities need right now is equity, it is not an aesthetic or a planning exercise.”

The intention of community engagement is to nurture public participation so that more may powerfully advocate their needs and shape the changes to come. Artist and activist Robbie Herbst observes that “great cities are defined by citizen-led culture and policy.”

‘Citizen-led’ means everyone may lead, regardless of title, background, language, or field. Camilo Cruz, whose art practice evolves parallel to his work in criminal justice, suggests that in this critical time, radical creativity must not be limited to those who think of themselves as artists, but that “all need to think of themselves as ‘artists’ so that we fulfill our destiny of hopeful evolution, rather than ignoble devolution.”

Artists instigate change by expressing authenticity, beauty, humanity, and humor; Planners guide change by leveraging regulations, data, economics and vision. The kind of equitable planning needed now in Los Angeles, however, would cultivate a wider range of participants to tap into their own knowledge and creative expression to become city-makers themselves. The most visionary changes to come may be initiated by people who do not yet consider themselves either ‘planners’ or ‘artists’. But it is up to today’s planners and artists to open doors for such evolution to occur. The future liveability of our city depends on it.

Comments (0)