The river Rhône has snaked its way through the French city of Lyon for centuries. However, in the last few decades the central section of the river banks had been in use as large car parking areas. Seeing the asset the river banks could be for its citizens, the city of Lyon took the initiative to transform the river front. The Urban Community of Lyon recently urged the reclamation of this site in order to return it to pedestrians. The areas allotted to car parking (1,600 parking places) have been reclaimed and the nearly five-kilometre stretch has been returned to the pedestrians. In comparison, the Sabarmati riverfront project in Ahmedabad is more than 11.5 km long.

Agency In Situ (landscape), together with agency Jourda (architecture) have been in charge of this major regeneration plan.

The project plays a role in the city’s urban transport plan, which aims to reduce car usage for daily journeys by encouraging the use of sustainable modes of transport. This, in turn, has allowed the regeneration of public spaces.

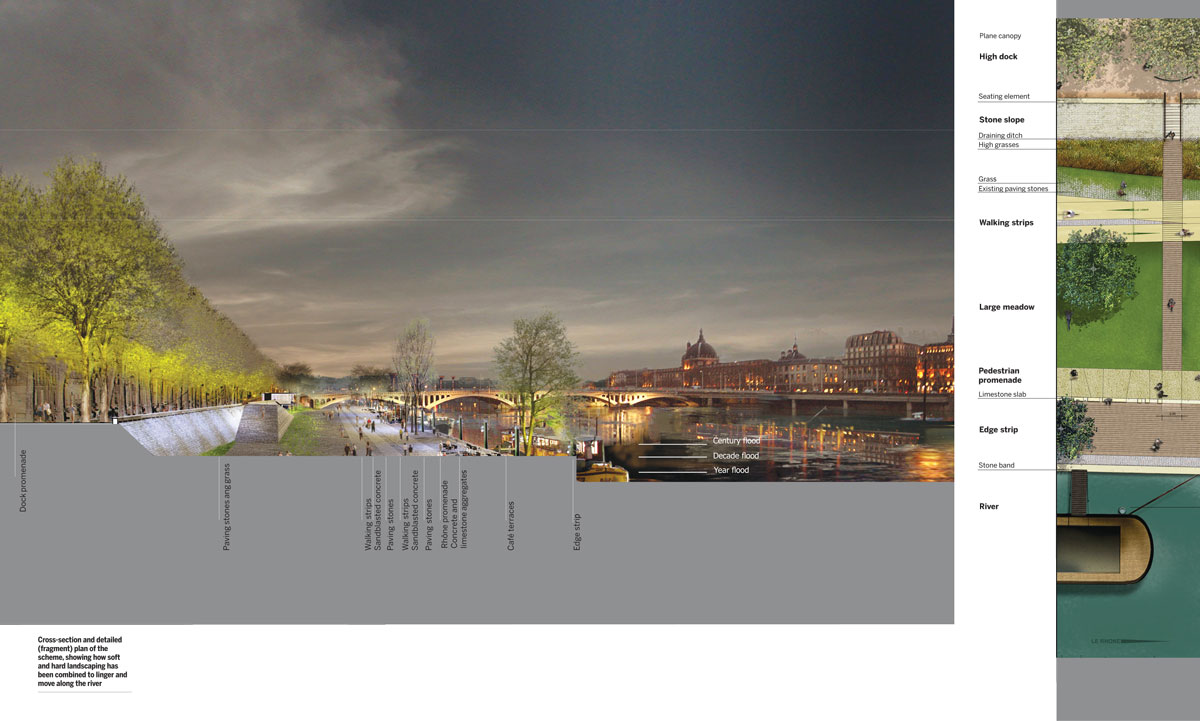

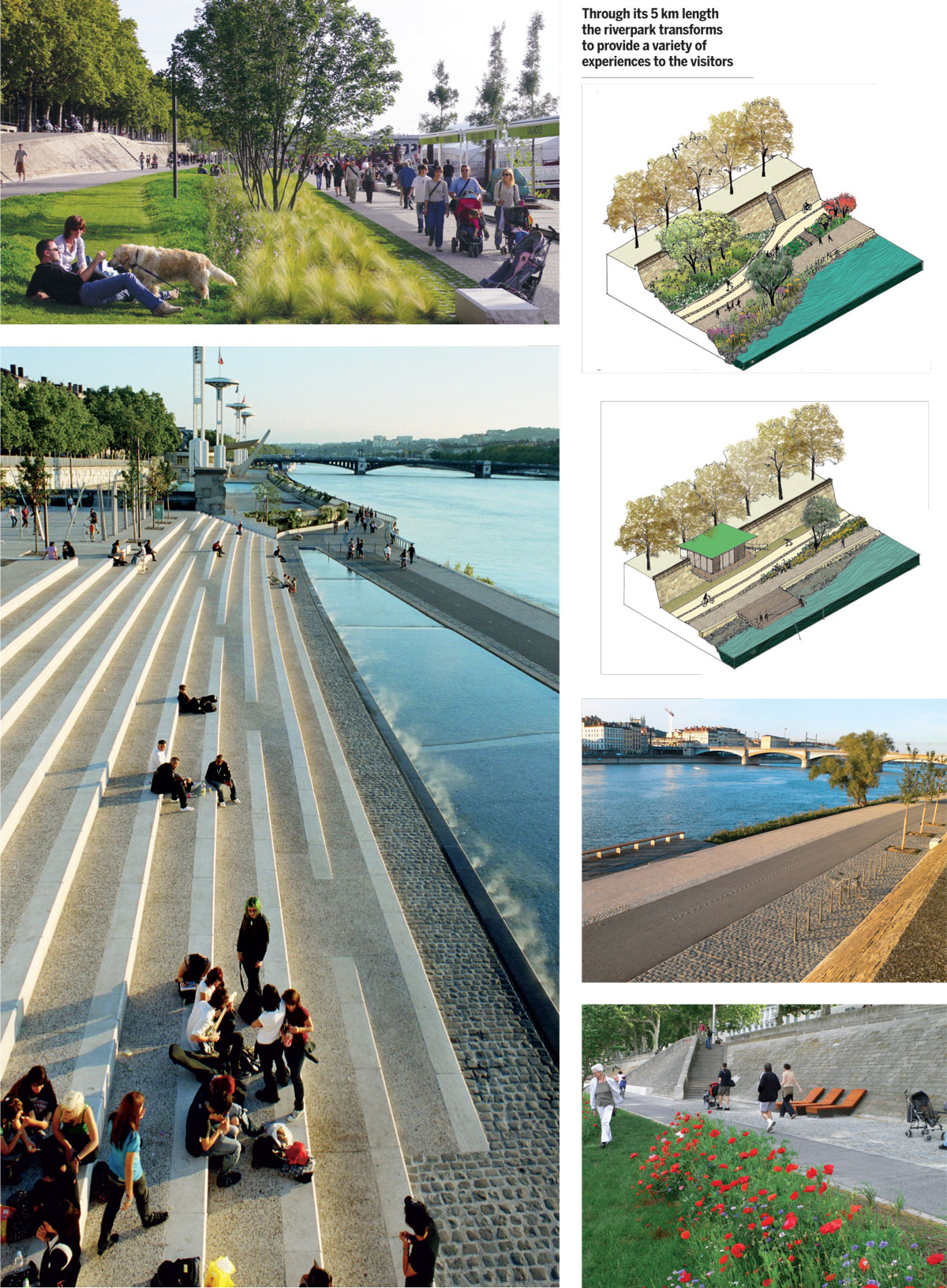

The Berges du Rhône development seeks to give city-dwellers a variety of areas in which they can relax and feel closer to nature. The riverbank’s area has very variable transverse widths (between 5 and 75 m), with very differentiated places, from more natural spaces upstream and downstream to more urban places in the central part. In the central part, in the broadest section, a large meadow off ers an open space close to the restaurants, barges and terraces settled on a wooden floor.

Important participatory work with the inhabitants and the maintenance services of the city has helped to define the uses of each section of the banks.

Upstream, the riverbank’s vegetation is the subject of ecological work of reactivation: digging, soft cut, constitution of islands and a refuge for beavers, planted with grass, coppices, willows and poplars, the islands serve as rainwater retention gardens on the edges of the wild barges.

Downstream, the existing quay was sterile and mineral; significant work was required for the riverbank’s regeneration. The vegetable gardens created along the botanical walk help to diversify the different types of ecosystems.

In the deep curve of the river, the quay is reorganised to develop generous planted terraces and steps in front of the river with the city’s landscape in the background. This very urban sequence connects the high quay and the riverbanks. The area close to the Rhône’s swimming pool is, with its playgrounds and skate parks, dedicated to sports activities.

This park walk is a course that connects multiple places and ecosystems. It is also a territory of mixed uses, which conciliates the activities of the surroundings and those of the city.

This project is both flexible and durable integrating either a maintenance strategy or the management of various spaces in time.

When the first sections were opened to the public in spring 2007, the development proved an immediate and massive success. Today, it is a space that has already firmly taken root in the day-to-day life of Lyon’s residents.

Fact Sheet :

Realisation: 2005 – 2007

Surface: 10 ha.-5 km long

Costs: 30 M €

Client: Le Grand Lyon,Service Espace public

Design: IN SITU

Landscaping: Emmanuel,Jalbert, Annie Tardivon, David Schulz, Yann, Chabod, Eve Marre, Marie-Gabrielle Beuvier

In collaboration with: F. Jourda Architect; Coup d’Eclat.Lighting & GEC, Rhône Alpes,Economist; Sogreah, Ingenior; Biotec,

Environment; Agibat, Ingenior; Sol paysage, Greenery.

Comments (0)