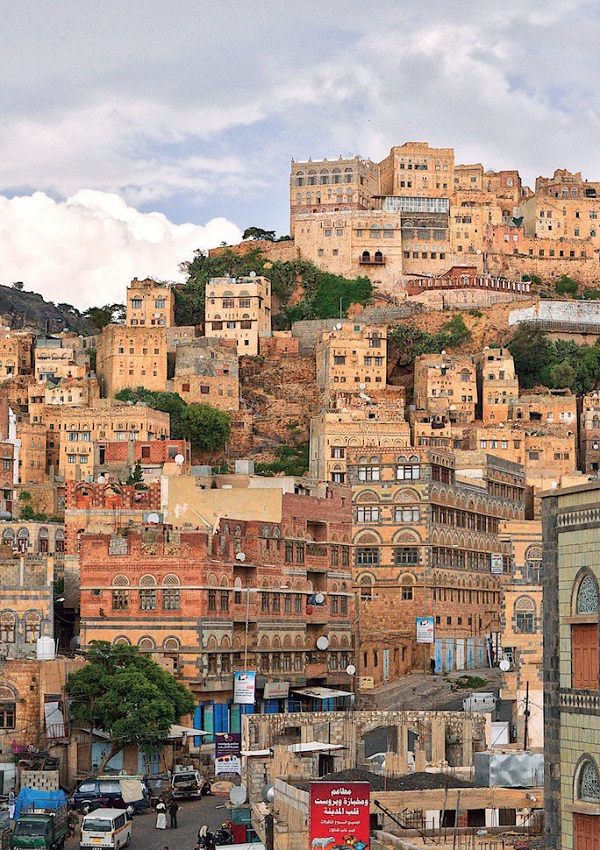

The cityscape of Yemen is shaped by palaces and residences carved in between mountaintops. High desert slopes and rocky hills dominate the central and western parts of the country. The Rub’ Al Khali Desert permeates nearly 250,000 square miles of sand crossing four countries (Figure 1). Large bodies of water are nonexistent and small streams that appear during the fall and winter seasons dry up in the summer heat. Water is not the only concern; inadequate land utilisation such as overgrazing, desertification and informal development is omnipresent. This article highlights the contemporary understanding of the ‘Informal City’ by examining the underpinning conditions of land development in Yemen. It further discusses how land use patterns become ‘informal’ and to what degree they fragment the spatial significance of the country.

The Middle East is a composite of 18 countries and has progressively become a multi-faceted development with the rise of globalisation, warfare, resistance and identity. Literary sources indicate that the Middle East has always been the host of traditionally-planned neighbourhoods, sacred spaces with religious importance as well as a place of discovery of raw land and resources that are treated as ‘hot’ consumer goods. With the scrutiny of other Middle East countries, Yemen has become a question of urban, social and territorial issues. The country has been fractured by the tumultuous Saudi-led war, humanitarian crises, with more than half of the country plunged into poverty and hunger; the absence of a feasible economic policy has left its spaces in ruins. Consequently, these factors beget housing deficits, low-standards of living and poor economic development. These are the watchwords of Urban Informality and Yemen has become the paragon of such urbanisation.

But, when and why did informality become a matter of concern in Yemen and a subject in mainstream urban planning and design history?

Much of urban planning literature reveals that the informal sector offers lessons to better understand marginalised settlements and their success in developing the very controversies surrounding them: community and economic injustice, housing and public space in precarious areas and the role of spatial practice to address such informal rules.

SOURCE: ARFAKHASHAD MUNAIM

Learning Urban Informality

Yemen is predominantly homogenous with the factions of Sunni Muslims and the Zaidiyyah Shi’ite Muslims making up nearly 40%. Other religious identities such as Christianity, Judaism and the Baha’i faith cumulatively total a population of 26 million inhabitants. Today, more than 40% of the country’s population lives in slum settlements (Figure 2); however, informal housing is no longer the domain of the urban poor, but also the middle-class and elite groups (Farajalla, N., Badran, A., et al., 2017, Pg. 19). Informality can only occur when there is severity of housing shortage and lack of funds for capital investment, which has now pushed its country to non-conventional sources: informal economy, informal governance, informal housing, informal spaces and informal living. These spaces no longer occur on the peripheral level of the city, but are integrated in the urban core (Figure 3).

Massive urbanisation is a contemporary phenomenon in Yemen. Since the establishment of the new Republic in 1961, Sana’a has become the capital city. Inevitably, Sana’a experienced a rapid rural-to-urban migration due to the inadequate development of agricultural lands, high levels of poverty and increasing unemployment rates in provincial towns. Poverty remains high with 40.1% of the population in rural areas and 20.7% of inhabitants in urban areas sinking below the poverty line. Informal urbanisation gained a threshold after another wave of migration following the 1991 Gulf War forcing nearly 800,000 Yemenis out of Saudi Arabia. Many Yemenis had been living and working in Saudi Arabia for decades while sending remittances to their families back home. The sudden exodus fragmented their assets and Yemenis returned home with a fraction of their wealth. Government assistance was also poor and inadequate while the national economy was suffering during the war. Many returnees were young men and rural inhabitants forced to find new livelihoods in Yemen’s cities.

SOURCE: YEOWATZUP (HTTPS://WWW.FLICKR.COM/PHOTOS/YEOWATZUP/)

SOURCE: YEOWATZUP (HTTPS://WWW.FLICKR.COM/PHOTOS/YEOWATZUP/)

It is common to find nearly 10 to 15 people in shared flats. The majority of individuals appear to be day labourers primarily in construction, artisan-related, commercial and service businesses. Since finances were scarce, they needed cheap housing. Most were successful in buying a plot of land near the fringe of major metropolitan areas where land was inexpensive and construction costs were low due to the absence of building licenses and building standards. Poor families were able to squat on empty State land for almost free near the urban centres and, over time, these areas became increasingly attractive to residents. These informal establishments are commonly referred to as ‘Madinet al-mughtaribeen’, meaning ‘City of the Returnees’, ‘Madinet Al-Leil’ or the ‘Night City’ due to its construction overnight by the forced returnees.

After the reunification of North and South Yemen in 1994, Sana’a became the political capital of the new Republic, enabling the city to invest in considerable improvements of services and economic opportunities. Moreso, the discovery of petroleum in the late 1990s and rising oil prices after the second Gulf war in 2003 empowered the State to invest in urban infrastructure. These investments helped expand urban economic sectors and generate a considerable amount of wealth for urban elites.

Thinking Informally: Post-Planning Neighbourhoods

While countries such as Turkey, Egypt and Iran have instituted modern design codes for the development of robust design and construction detailing, the formal construction process is beyond the economic means in Yemen (Bosher & Lee, 2008, Pg. 231). Although there is no standard definition of informal development, it is typically referred to as an area that has been squatted or subdivided without any regulatory provisions.

The absence of building regulations and building licenses are the norm for informal development (Figure 4). These areas are labeled as ‘ashwa’I’ and the practice is considered as ‘manatiq ’ashwa’iya mukhatata,’ meaning planning informal areas or ‘takhtit ‘ashwa’I’, meaning random planning (Shorbagi, 2008, Pg. 4).

The General Authority for Land, Surveying and Urban Planning (GALSUP), is the governing planning agency responsible for master planning new neighbourhoods (referred to as mukhatatat wahdat al-gawar). These plans generally consist of a street layout with essential services, including a school, a mosque and a garden. Unlike formal plans that are composed with a community vision, Yemen’s residential neighbourhoods are not integrated into any broad or structural development planning (Figure 5). Planning practice is made ‘re-active’ by developing an area after it has begun informally or using the existing layout and then focusing on residential use. It does not consider any economic activities such as commercial centres or industrial workplaces. In other cases, roads, utilities and social services are provided before a detailed plan is prepared, making neighbourhood planning irrelevant (Figure 6). Consequently, post-planned areas resemble unplanned areas (Shorbagi, 2008, Pp. 4-5). Furthermore, detailed planning often relies on incomplete and outdated cartographic information. For example, the GALSUP in Sana’a uses satellite images from 2002, which are incomprehensible and lack a clear distinction between property boundary lines. In addition, property owners avoid applying for building licenses due to the time-consuming and costly procedures (Shorbagi, 2008, Pg. 5).

SOURCE: ROD WADDINGTON (HTTPS://WWW.FLICKR.COM/PHOTOS/ROD_WADDINGTON/)

SOURCE: YEOWATZUP (HTTPS://WWW.FLICKR.COM/PHOTOS/YEOWATZUP/)

The Distribution of Informal Land in Yemen

State public land is very scarce and typically located in the mountains (Figure 7). The State also lacks land surveys and databases of their own land to verify and establish property boundaries and facilitate encroachment by private individuals. There is no means for the government to recoup any land servicing costs. For example, the government is required to compensate landowners for taking away more than 25% of a land parcel for streets or public facilities and is also required to purchase the private land for the construction of social services (Shorbagi, 2008, Pp. 34-35).

Furthermore, GALSUP also lacks an appropriate land registration inventory. Since most private land is not registered, it is taxing to demarcate exact boundaries and the only available information is vignettes attached to the land’s registered file. The State has nominal power to protect private property rights and, in most cases, land is traded informally with the use of basa’ir or written documents. The basa’ir is a certified document by two witnesses that attests the sale, rent or inheritance of land (Shorbagi, 2008, Pp. 34-35). It is drafted by an amin al-mantiqa, a government chief appointed to a designated area who certifies the document related to property transactions and personal status issues. The basa’ir contains a description for the location of the land, information on the buyer and seller and the transaction history of the land. The basa’ir registration requires only signatures of the parties involved and requires no verification of property rights of the original owner or seller.

Vacant parcels in squatter settlements and areas where construction is prohibited (i.e. environmental hazards or security reasons) are the cheapest. Squatting is another cheap way to obtain land ownership.

While evictions from the State are generally rare, squatters are able to build tents after squatting on the land. Gradually, individuals claim ‘ownership’ of the land and begin to subdivide or sell it for profit; other individuals may build structures and rent them out to poor families.

Most of these private land investors often occupy large parcels of land and claim non-agricultural land as agricultural space. Therefore, it forces the State to prove ownership without having any knowledge of the boundaries of public land (Shorbagi, 2008, Pp. 34-35). Landowners are often supported by small informal contractors to provide a range of products and services to expand housing for financial resources (Shobragi, 2008, Pg. 31). Land prices increase as soon as post-planning starts in an area and are significantly higher in areas near major access roads or transportation lines (Figure 8) (Shobragi, 2008, Pg. 22). In some areas, owners will sell their plots and buildings to wealthier buyers who combine adjacent tracts for larger construction projects. The sellers tend to buy land in another, yet unplanned area, where land is cheaper and invest in the construction of better buildings. In many fringe areas, which were post-planned during the first five years of the new millennium, land prices soared from nearly 30,000 Yemeni Rial (equivalent to US $120 dollars) up to 80,000 Yemeni Rial (equivalent to US $319 dollars), whereas, approved neighbourhood plans completed with utilities, services and access rose to 300,000 Yemeni Rial (equivalent to approximately US $1,200 dollars). (Shobragi, 2008, Pg. 31)

SOURCE: ROD WADDINGTON (HTTPS://WWW.FLICKR.COM/PHOTOS/ROD_WADDINGTON/)

Fixing Informal Urbanisation in the 21st Century

Land disputes are common considering the unorthodox practice of regional planning in Yemen.

In many ways, it is manipulated and the country’s judicial system does not provide an effective protection of property rights nor does the government succeed in controlling informal development by prohibition. Due to the lack of data and scarce property information, land disputes are most common with the State on mountain slopes.

The 1995 property law attempted to regulate customary rights to mountain slopes above agricultural land that are linked to the customary rights to use water from the mountains for irrigation. The State interprets the law by allowing private landowners to claim 20% of the mountain land on slopes adjacent to their agricultural land and claim the remaining 80% as public land.

However, property owners dispute the mountain land that is below 20% slopes for the purpose of protecting their water resources (Shobragi, 2008, Pg. 29). Even then, State lands can be found in upgrading areas; the only currently available mechanisms to sell this land to generate funds for further infrastructure development requires a special decree from the Prime Minister. There is no cost recovery mechanism for roads or public spaces. The irregular property tax does not recover a portion of the increase of land and property values in upgrading areas. In other words, there are no current opportunities or financial resources for the State to act as a land developer.

Furthermore, the government does not have any strategy to guide informality in Yemen, primarily due to low cost recovery of utilities and lack of incentives for property owners. Yet, these challenges have prompted few urban interventions and policy initiatives to remedy informal urbanisation.

For example, the Sana’a Municipality is in the process of developing ‘Sana’a 2025’ for long-term City Development Strategy (CDS). The study aims to help the City to understand the threat of informality and offer recommendations to build strategic investment opportunities, streamline procedures and create an attractive business incubator to contribute to the overall sustainability of the country’s economy.

Furthermore, the Yemen Port Cities Development Program (PCDP) is another goal for the World Bank to address economic development and sustainable growth. In 2003, the World Bank approved a US $23 million credit to the country, which includes the development of Yemen’s coastal cities including Aden, Hodeidah and Mukalla over the course of 12 years at a total cost of US $96 million. The first phase will aim to support local government building and strategy planning, small-scale infrastructure improvements and create a participatory development process (Madbouly, 2009, Pg. 15).

Comments (0)