Users of public infrastructure are unlike typical users of consumer goods in that they don’t own what they are using; they are only renting, and sometimes for free. By using the exercise equipment in a park, people don’t have to worry about the developing rust or the peeling paint on its bars. They may not feel the need to advocate for its cleanliness, set aside a budget for its maintenance, or care for the aesthetics, probably because it is not their own. They didn’t choose to purchase it, investing a sum of money for their benefit and therefore may not see reason for it to reflect their personal preferences.

In the world of infrastructure, this means that building ownership to publicly offered tools, services and products could be an issue. How can we encourage people to care about something they don’t own or choose to buy, but still value it as an amenity? In some form or the other, this issue exists across various types of infrastructure: road signs, bike racks, ticketing machines, transit stations, bus stops and so on. How can we get users to clean up after themselves, value and respect offerings they may take for granted?

One way is to bring them along on the design process. Building engagement right from conception through implementation can define attachment, ownership and responsibility toward the product or service in question. Moreover, connecting with potential users throughout the process ensures relevance to them and the community at large. This begs the question: what incentive does the user have to carve time out of their busy day to worry about an upcoming bus stop?

Provocation may be key here; giving potential users the reason to take interest may trigger eventual ownership. Communicating the value and impact of their participation in a bold, simple way may be able to attract their attention. Provocative campaigns have in the past proven to accomplish this goal across diverse scales, industries and geographies.

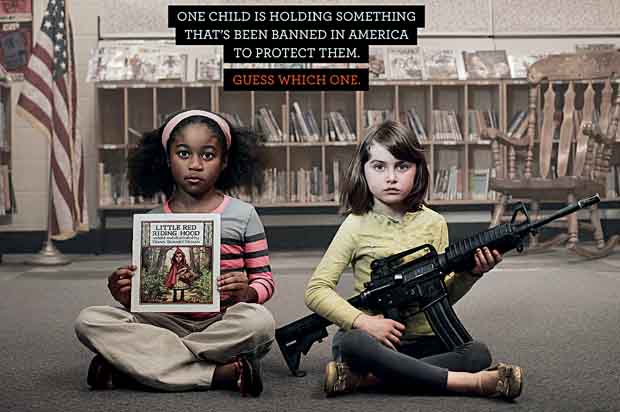

Top Right: Clever, clean and bold, DesignBridge’s materials attracting entries to their annual DB Awards competition show insightful understanding of their target users Bottom: “We keep ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ out of schools because of the bottle of wine in her basket. Why not assault weapons?” |

Take for example, Moms Demand Action For Gun Sense In America, the grassroots movement in the USA fighting for safety from gun violence. In 2013, they launched a compelling poster campaign showcasing the irony of ordinary things like dodgeball, Easter egg treats and books like Little Red Riding Hood that have been banned for the ‘safety’ of children while assault weapons are not. The tenderness of the subject no doubt created awareness, but clever and bold design does not go ignored. In 2018, beer mats, bottle labels and posters from Design Bridge inviting participation in their annual DB Awards provoked responses and winners of the competition have since been hired as employees.

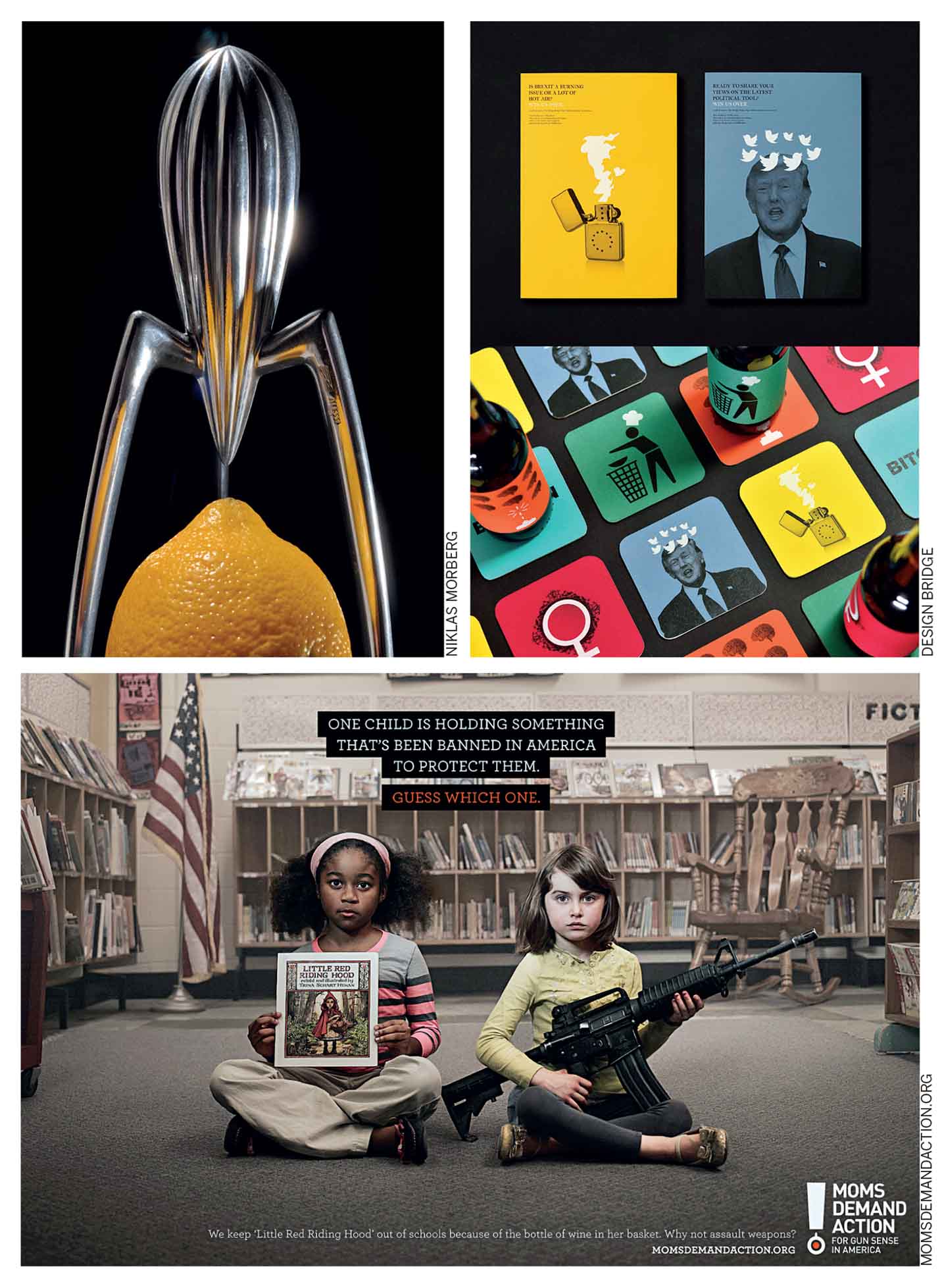

Even in the world of products, provocation through design, materials and proportion has successfully caught the attention of users, potential users and even unrelated passersby. Jurgen Bey’s Daytripper bus stop, Phillipe Stark’s Salif Lemon Squeezer, Front Design Studio’s animal lamps and several others provoke users, prompting discussion, challenging the status quo and demanding change.

How might the process of design itself be provocative, so that users recognise the collective responsibility of being part of the conception and shaping the outcome?

How might the process of design itself be provocative so that users recognise the collective responsibility of being part of the conception and shaping the outcome? Simultaneous research tracks may be necessary: one that uncovers latent needs through observation and another that presents users with an exaggerated future scenario of the way design is about to shape their everyday life. The latter is a direct tool to showcase impact of the design intervention whether it’s a product, service or space to grab attention and show how ignoring the invite to participate may result in a possibly disagreeable consequence.

The scenario must be communicated visibly and boldly and allow both qualitative and quantitative participation. Pamphlets in the mail, scenario illustrations on banners, painting on temporary walls, projections on buildings, scrappy installations, local museum exhibits and so on, are creative ways to engage a diagonal section of the target market. Users would then be invited to share opinions on the scenario, suggesting changes and building refinements.

As a next step, it is critical to iterate the scenario and therefore the design, based on received comments and share it back with the community. With every iteration, the process comes closer to building a more effectiveand relevant offering. Parallel to this, cyclical engagement with users throughout the life cycle of the product, service or space helps them understand the way they shaped it, reinforcing ownership. Continuing this participatory approach beyond its life cycle gives users further voice in the next avatar of infrastructure elements they use every day.

Imagine a future where a father shows off the design for the local park fence to his daughter: an idea he came up with. Such is the potential of attachment to infrastructure.

Comments (0)