The Panama Canal stretches for 77 kilometres across Central America to connect the Pacific and Atlantic oceans and completed 100 years on August 15, 2014. Before its construction, ships would have to travel for days to get from the Pacific to the Atlantic waters, via the hazardous Cape Horn and the Straits of Magellan. The canal’s opening in 1914 shortened the route to about 8 hours. Today, close to 15,000 ships transit through this mega-infrastructure each year. And with the canal’s expansion of two new sets of locks since June 2016, this traffic is expected to increase both in individual ship size and overall numbers, adding to the national economy. As an engineering mega-project that has today become a world-famous monument of sorts, the Panama Canal represents both an emblem of human progress as well as a multi-generational conquest of nature.

But mega-infrastructures like the Panama Canal do not conquer nature as much as they massively transform it. The canal’s original completion and expansion have had dramatic environmental implications. The land bridge between North and South America is severed. Hundreds of wetlands have been drained or filled and thousands of acres of jungle submerged under a new manmade lake. Entire ecosystems have been poisoned with thousands of gallons of crude oil. While environmental issues were not a concern when the canal was being built, today the canal’s intertwined ecological and infrastructural dimensions are increasingly coming to the forefront. The intent of this essay is to overview some of these dimensions and offer deeper reflections on how one might read the Panama Canal’s present and future.

Mega-infrastructures like the Panama Canal do not conquer nature as much as they massively transform it

Infrastructure

As an infrastructural project, the Panama Canal represents the mega-transformation of a vast and complex hydrological terrain spanning two of the planet’s largest water bodies. Geographically speaking, the tidal waters of the Pacific Ocean rise to higher levels than in the Atlantic, and navigating a ship from one side to the other through a man-made channel is no small challenge. The Panama Canal achieves this by raising or lowering a ship from the Pacific or Atlantic water level and this entire operation is achieved by moving water via pure gravity.

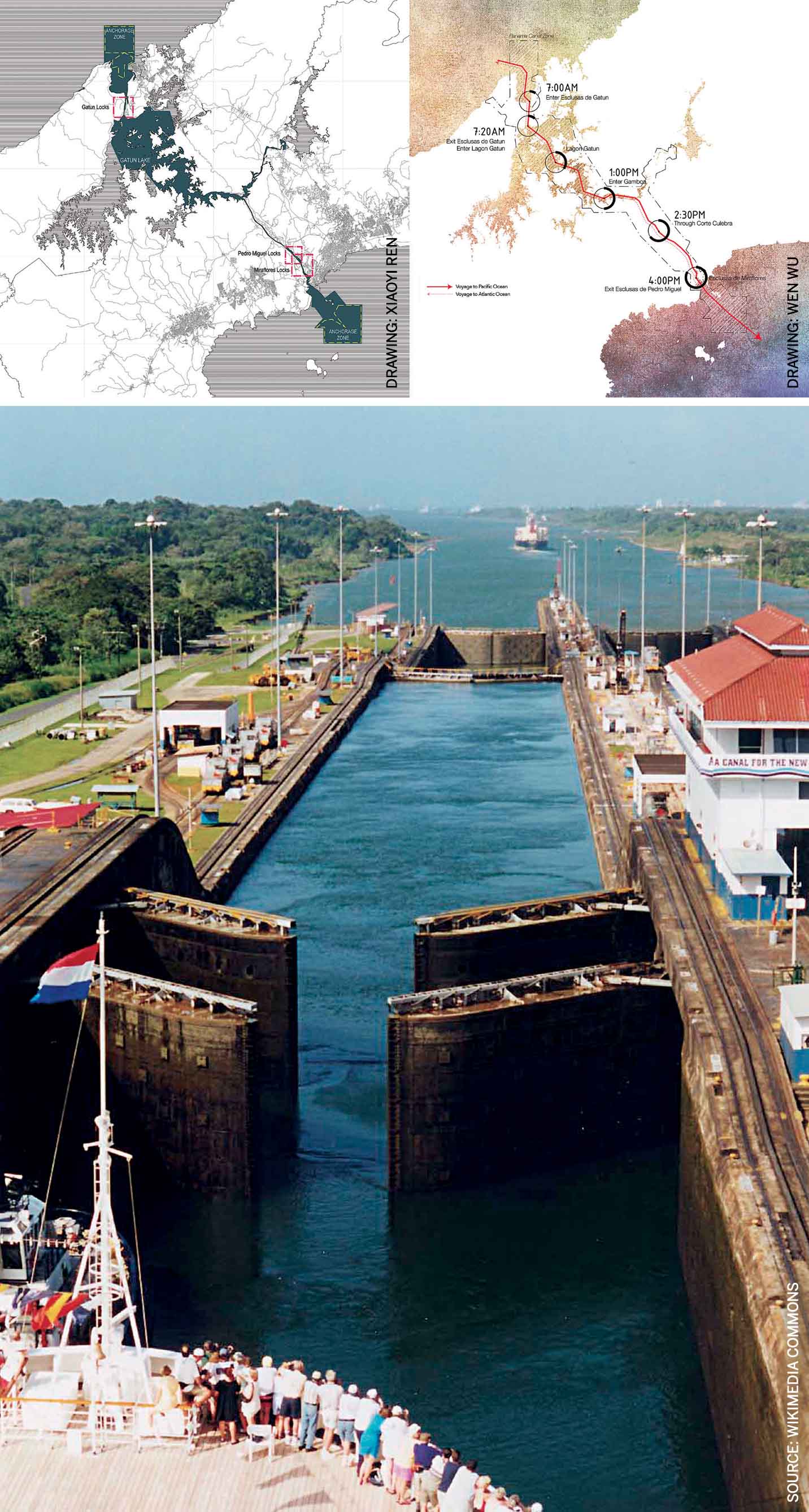

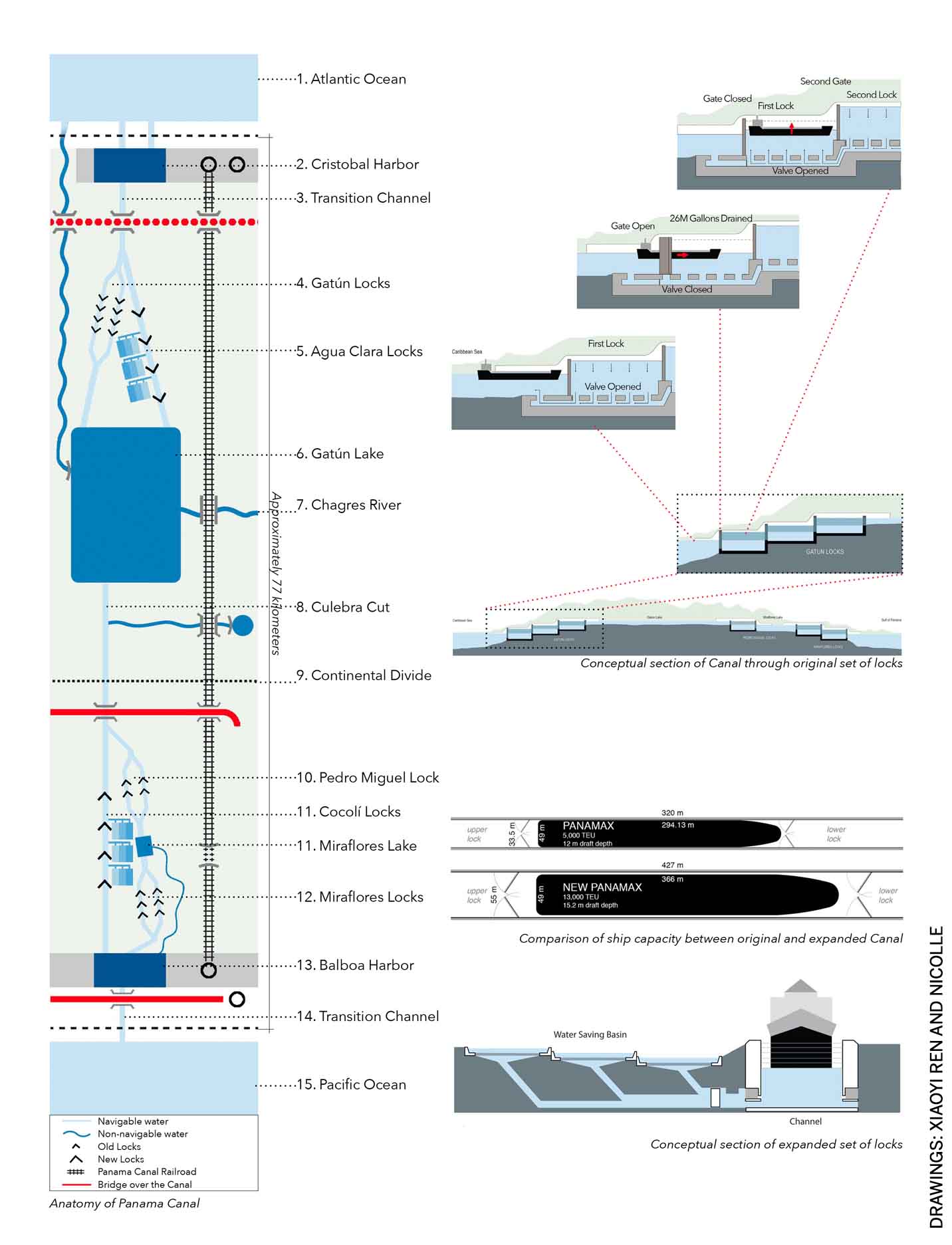

To accomplish this operation, the canal has a 77-metre-long infrastructural anatomy of distinct elements catering to specific steps within a larger ship navigation sequence. A ship’s journey through the canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific side begins with an 8.4-kilometre natural harbour called Limón Bay that also provides a deep-water port for multimodal cargo exchange and trade. A 3.2-kilometre channel then creates a transition to the 1.9 kilometre Gatun Locks that lifts the ship to the Gatun Lake level some 27 metres above sea level. The ship enters the Gatun Lake, an artificial water body formed by the building of the Gatun Dam, and traverses 24 kilometres across the isthmus. It then reaches the 8.5 kilometre natural waterway called the Chagres River, before making it to the 12.4 kilometre Culebra Cut slicing through the mountain ridge and crossing the continental divide. The ship then reaches the first part of its descent via the 1.4 kilometre-long Pedro Miguel Locks and enters the 1.7 kilometre-long Miraflores Lake located 16 metres above sea level. It then passes through the two-stage Miraflores Locks for another 1.7 kilometres descending further to reach Balboa Harbour. And it is from here that the ship finally exits through a 13.2-kilometre channel to the Pacific Ocean. For ships coming and going from the Pacific side to the Atlantic, this sequence is reversed.

Top Right: Timeline of ship route through canal from Atlantic to Pacific

Bottom: The gates of one of the canal’s locks open to let a ship through

The canal’s most impressive infrastructural elements are its massive gates ranging from 14-25 metres in height and more than 2 metres in thickness. The heaviest of these gates weighs more than 600 tons, with the hinges themselves weighing more than 16 tons each. Each gate has two leaves, around 20 metres wide. When they close, they always point upstream, with the force of the water from the higher side firmly pushing their ends together. The gates can be opened only when the water level equalises on both sides. The gates are hollow and buoyant and so well balanced that two 19 kw motors are enough to move each leaf. If one motor fails, the other can still operate the gate at reduced speed.

Since June 2016, with the completion of the Panama Canal expansion project, the canal has two new sets of locks, one each on the Atlantic and Pacific side. Each lock has nine lateral water-saving basins and, like the original locks, these 18 new basins get filled and emptied by gravity, without the use of pumps. This expansion has doubled the canal’s capacity to accommodate larger ships by widening and deepening its existing channels. The original locks could accommodate a maximum ship size of 320.04 metres in length, 33.53 metres in width and 12.56 metres in depth. The expansion accommodates ships as large as 427 metres long, 55 metres wide and 18.3 metres in depth.

Ecology

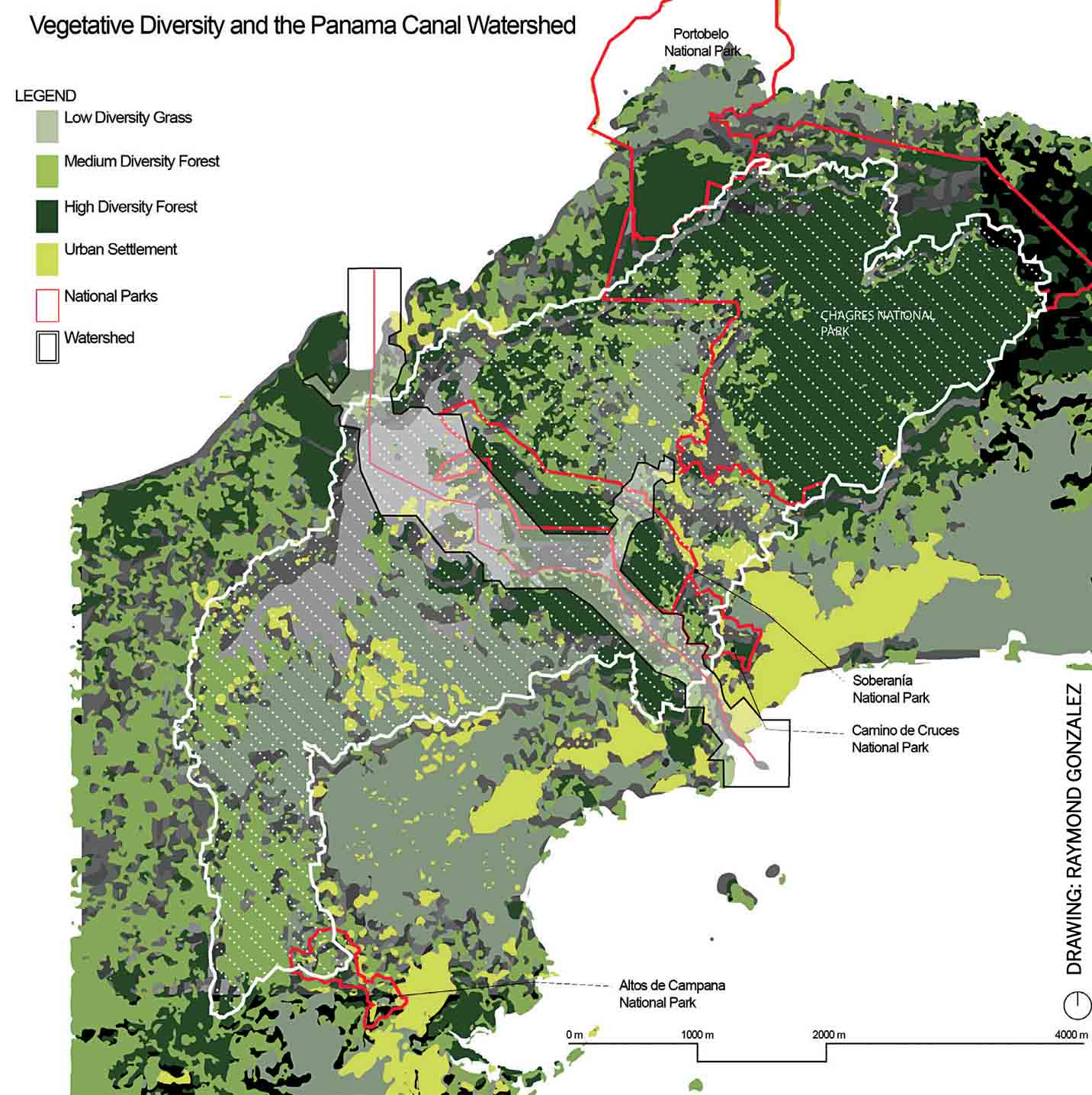

The Panama Canal is not just an impressive mega-infrastructure, but also a macro-ecology situated within a vast, rich and varied regional watershed. As such, the Panama Canal must be understood as a single macro-landscape with enmeshed ecological, infrastructural and hydrological dimensions. Panama is a transitional ecological region between North and South America containing four tropical domains all correlated to its high altitude, temperatures and rainfall. The first of these are mountain rainforests with constantly humid oceanic and windward slopes. The second is rainforests with short dry seasons. The third is seasonally humid and predominantly deciduous forests. The fourth is perennially humid rainforests. This rich, complex eco region sweeps across the canal zone and, as such, the canal corridor contains more than 1000 tree species even as the canal watershed holds up to 2,300 species, comprising 60-70% of the country’s total types.

The continuing economic success of the canal can be the incentive needed to conserve and preserve the rich ecology

The watershed that feeds the surrounding lakes and basins and enables this diverse ecosystem to thrive is also what sustains the canal’s functioning. It stretches from the Chagres National Park, north-east of the canal, to the Altos de Campana National Park to the south-west. Its vegetation ranges from tropical rainforests, savanna grasslands and shrub-lands exposed to high winds. The canal’s hydrology is extensive: total annual water runoff across the canal watershed is approximately 4.4 billion cubic metres, with more than half of it contributing to filling the canal’s locks and an additional 1.2 billion cubic metres used at the Gatun Dam to generate electricity for the canal’s operation.

There is thus an inextricable relationship between the ecology and infrastructure of the Canal Zone and the degradation of its ecosystem can have adverse effects on the Panama Canal’s operations and economy. While the Panama Canal Authority or the National Environmental Authority of Panama protects the watersheds that support the canal’s vegetation and forests, growing deforestation within the watersheds is raising numerous concerns. Each time a ship navigates the canal, 52 million gallons of fresh water are discharged from the locks into the ocean. This water comes from the Canal Zone’s watershed. If devoid of trees, it would break the ecosystem’s cycle therefore impacting the ability to restore its water. It can increase soil erosion and silt can raise the bottom of the canal’s man-made lakes reducing their storage capacity and, by extension, the canal’s efficient functioning.

Habitat

The Panama Canal Zone has been a place of selective habitation from the beginning, since it was a US-controlled territory until 1999. According to the 1912 census (two years before the canal opened), the zone’s population was 62,000. The canal’s construction drew diverse people to the location, with as many as 40 nationalities listed in the census. The zone was divided into two sections, the Pacific side and the Atlantic side, separated by the Gatun Lake, with US Government-created utilitarian townships catering to workers’ basic needs and leisure.

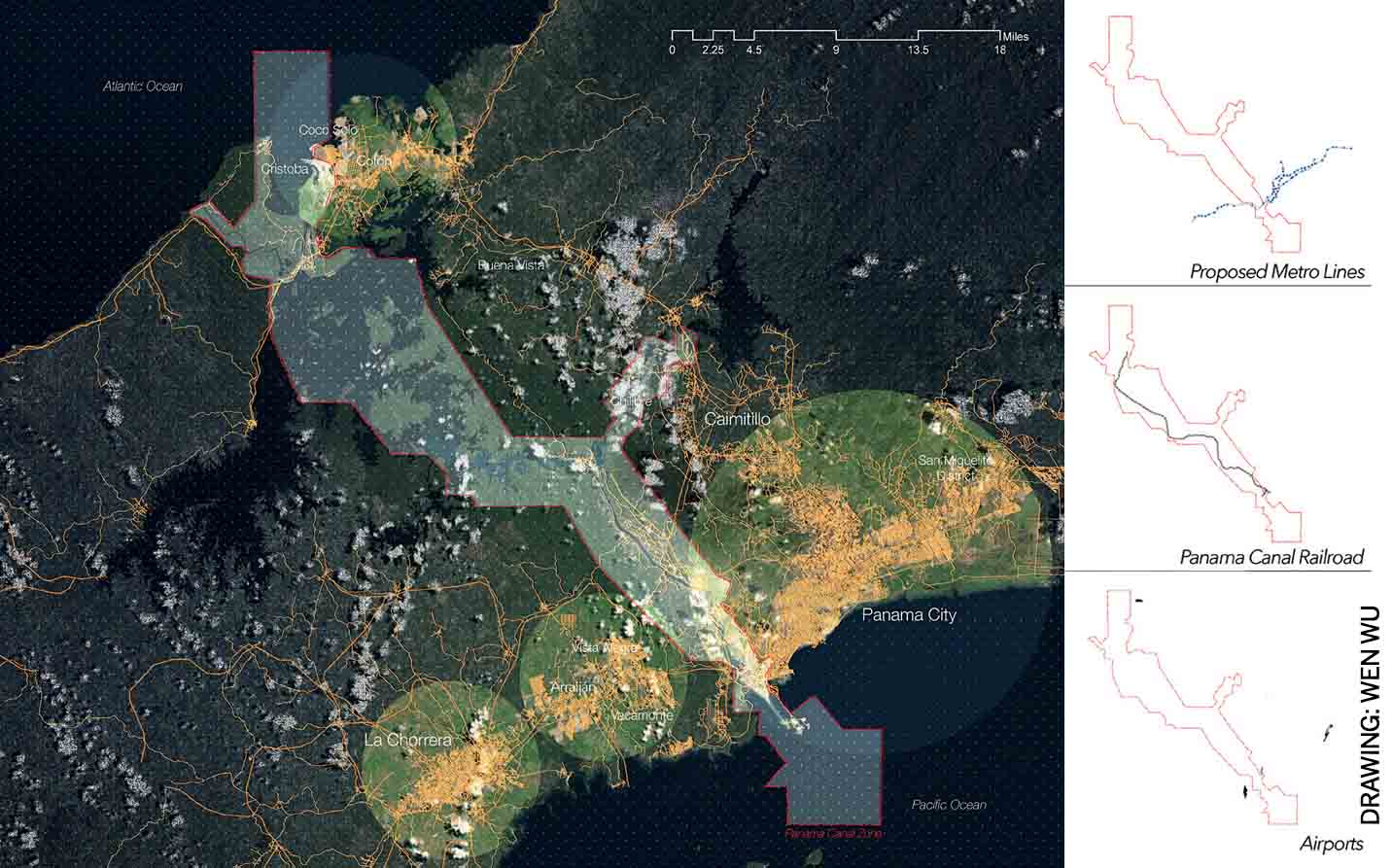

Right: Current and Future Mobility around the Panama Canal

Today the Canal Zone is open to Panamanian nationals and can be accessed by a well-established, multi-modal network. There is a railway that runs from Panama to Colon within the Canal Zone and three proposed metro lines run across the zone connecting to the rest of the province of Panama City. There are approximately 950 populated towns and villages spread along the canal’s east-west region within the provinces of Panama, Coclé and Colon, most located more than an hour’s drive from the canal itself. Ongoing mobility and infrastructure planning efforts need to consider strategies to connect these habitats to the canal proper, because the Panama Canal and its expansion programme has created and provided over 50,000 jobs till 2016.

There is an inextricable relationship between the ecology and infrastructure of the Canal Zone

With the canal’s world-class upgrade and future plans, the Canal Zone should be envisioned as a sustainable and eco-friendly habitus where people employed in the canal can also live close to it. With the grand opening of the expansion programme, increase in ship traffic is expected to contribute well to the local economy. But the projected revenue from the Panama Canal tolls will not be a significant contribution to government income. While this would appear to support an argument for additional revenue through responsible development closer to the canal, the track record of development in the 1,000 square mile watershed has often been haphazard and unplanned. The dialogue surrounding the canal’s larger future is steeped in numerous complexities that will need multifaceted investigations.

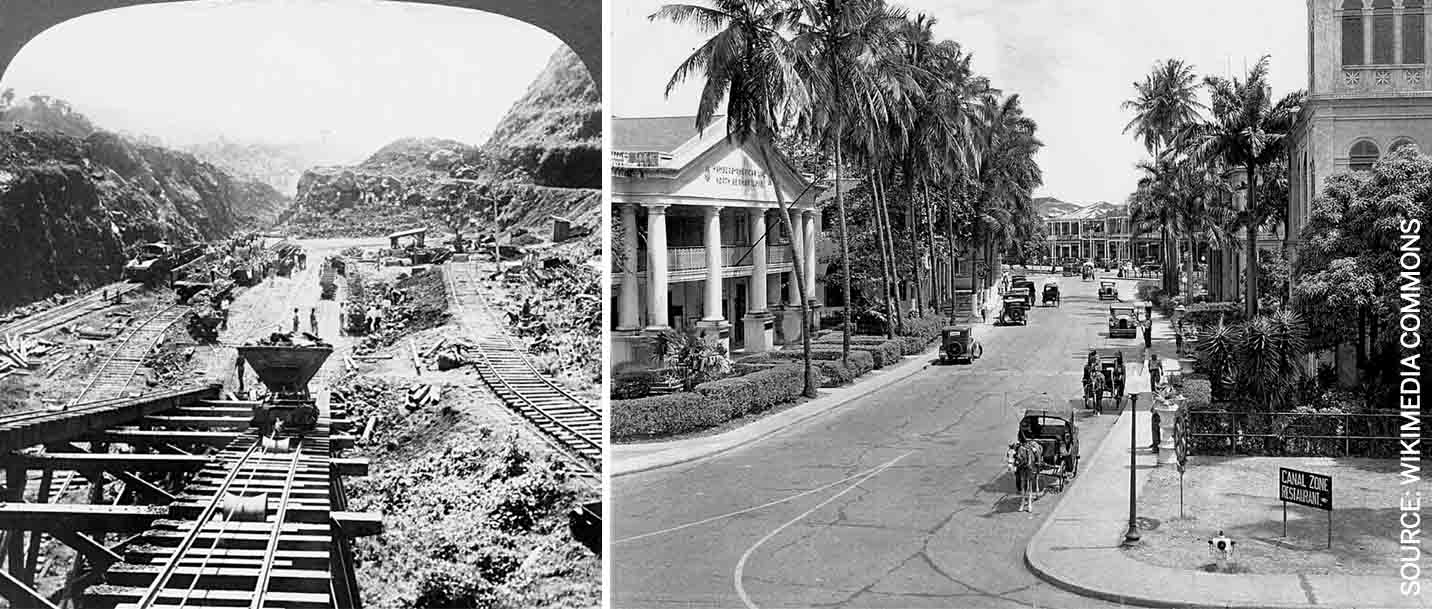

Right: Archival photo showing street in the town of Cristobal in the United States controlled Canal Zone, circa 1933

Conclusion

The Panama Canal brings in about US$ 2 billion in revenue each year, of which around US$ 800 million go into Panama’s general treasury. This accounts for around 4% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). While this number may seem meagre, the canal’s larger economic impacts cannot be underestimated. For example, the income of canal employees fuels businesses such as grocery stores, restaurants, schools and real estate. In this sense, the canal’s economic contribution, due to its sheer presence and related influences, might be as much as 30% of the country’s GDP. And with its expansion complete, some estimate that as much as 40% of the $ 5.5 billion investment will be recovered over the next five years.

While the economic value of the Panama Canal is indisputable, the other aspects that remain crucial to its long-term viability need to be brought to the forefront. Dominant among these are its environmental impacts and ecological implications and while this may seem at first glance like a challenge, it can also be read as a great opportunity. If one understands the delicate relationship between the ecosystem and the canal’s workings, the continuing economic success of the canal can be the incentive needed to conserve and preserve this rich ecology. In other words, the watershed, the forests and the vegetation that frame the Canal Zone must be recognised as a fundamental and essential aspect of any planning decision on the canal’s future. The intent of this essay is to underscore this idea and situate it as the foundation of all the planning processes and projects that will chart the future of the Panama Canal as both a global infrastructure for commerce and trade as well as a sustainable and eco-friendly local habitat.

We wish to thank Manuel Trute, Planning Director of Panama City, for sharing base materials and information on the Panama Canal. We also thank our student research team from the USC School of Architecture: Wen Wu, Xiaouyi Ren, Jingchen Zhao & Raymond Gonzalez.

Comments (0)