Drawings of young children express the most precious aspects of their lives: a safe home, a happy family, a loyal pet and lovely trees, which all require cities that keep them safe and comfortable. It doesn’t matter where in the world these children live or to which social class they belong. A safe home, provides families with a refuge from the climate. But what happens when the climate changes?

A safe home is also of concern for cities. When climate change is considered in the design or redesign of cities, the livelihoods of families are likely to remain stable for longer. Hence, climate change could be a key opportunity to improve the condition of people’s daily life by creating alternative pathways for solving deeply rooted social and environmental problems that most affect vulnerable populations. The need of climate adaptive housing could help in rethinking the regular system offering a new understanding of exchanges between society and ecosystems. A socio-ecological approach to adapt to climate change can give cities the opportunity to reshuffle technologies and policies that are not helping vulnerable communities achieve resilience.

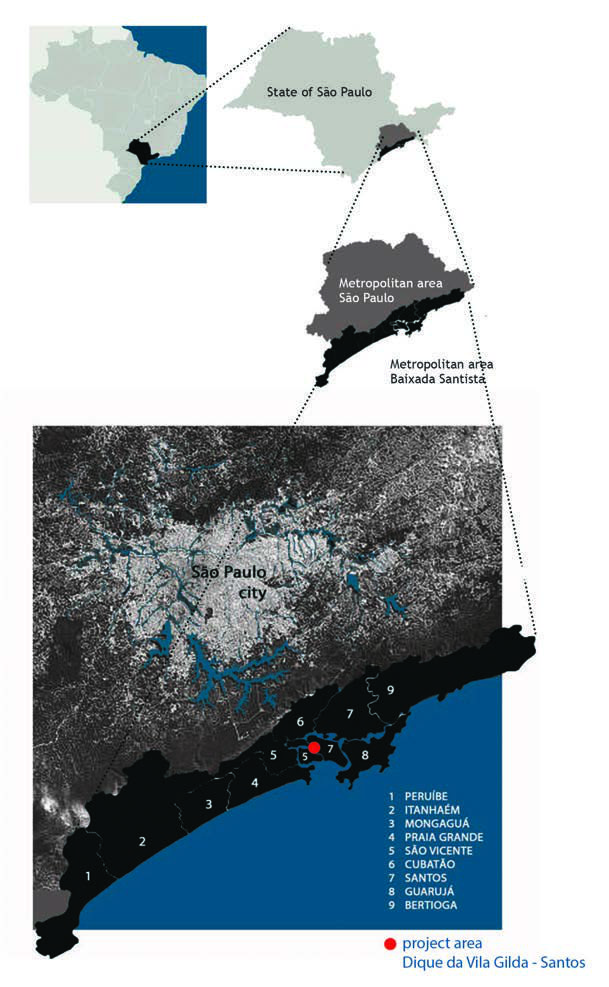

Metropolis Baixada Santista and the city of Santos, Brazil

The metropolitan area Baixada Santista is situated along the coast, 70 km from the city of São Paulo, about an hour’s drive through a mountainous landscape of Atlantic rainforest and through mangrove forests close to the coastline. It’s one of the most populated areas in the state of São Paulo and as a result of its port complex, has an important industrial role and is also a strong tourist attraction.

The city of Santos, founded in 1546 by the Portuguese nobleman Brás Cubas, is partially located on the island of São Vicente – which harbours both the city of Santos and the city of São Vicente – and partially on the mainland.

The city’s first major boom came in the 1860s when the opening of rail links connecting the port to the rest of the state made it the key shipping point for coffee producers in the state of São Paulo. Today, the port exports far more than just coffee. It possesses a wide variety of cargo-handling terminals for solid and liquid bulk, containers and general cargo loads.

As a city in an estuarine area with South America’s largest international port, Santos feels a part of the battle against climate change and is trying to become a more resilient city. Santos has about 420,000 inhabitants and is facing significant impact from climate change, which has potentially serious consequences for human health, livelihoods and assets. Flooding in the city is a result of intense rain as well as the sea tides.

Situated in a sub-tropical mangrove system, the urban development of Santos has a long relationship with water; its economic importance – the port and tourism – as well as the master plan proposed by engineer Saturnino Brito in 1910, where water management, urban planning, infrastructure and climate control have all been integrated in one design for the East zone.

Both prosperity and poverty face the same challenge: climate change

Due to the impact of climate change, the municipality of Santos is prioritising policies and plans to achieve a solution for the frequent floods. Ironically, the inhabitants of the prosperous neighbourhoods on the South and East zones are enmeshed in their properties depending mainly on adaptive measures and redesign of the infrastructure of their surroundings because their houses are not flexible enough for this adaptation. On the other hand, the structure of the poor neighbourhoods in the Northwest is so fragile that the value of the houses in this area is not an obstacle to finding new and innovative solutions.

The ability of vulnerable communities to meet their most basic needs – water, energy, sanitation – has been threatened by the segregated governmental policies, and is also the source of its risks and weaknesses. Climate change may lead to new insights that may contribute to a sustainable and integrated future development of the Northwest towards climate adaptation and climate mitigation.

Informal settlements

In the city of Santos, as in many others in Brazil, urbanization has become synonymous with slum formation.

The slum’s population – informally settled along the estuary’s water edges – is one of the urgent issues. The very limited land available for construction purposes increases the price of the building land making it unaffordable for social housing, even if the area for this purpose is formerly indicated in the cities’ spatial planning.

Officials are constantly looking for solutions for the resettling of the people living in the precarious stilt communities, which are nowadays illegally located in preserved mangrove forest areas.

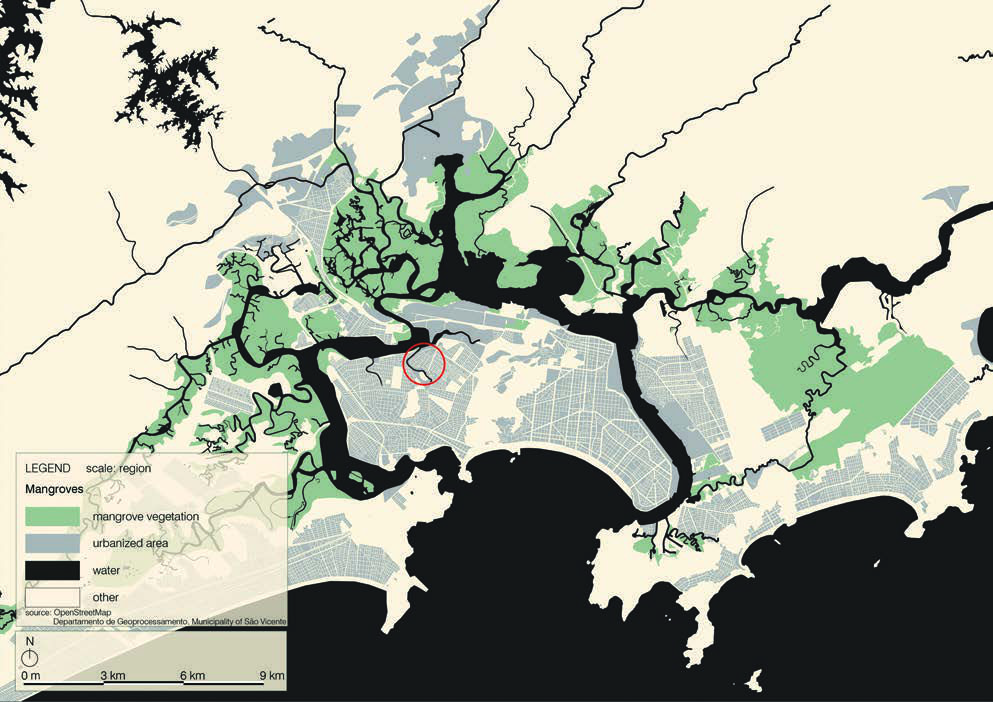

Due to slum formation along the estuary, mangrove forests are disappearing. Santos is facing the consequences of having to invest in infrastructure projects to solve problems such as flooding, sedimentation and silting up of the water bodies, natural resource depletion, destruction of ecological services and sea level rise. These settlements have to be removed from the mangrove area to enable the local ecosystem services to recover.

Northwest zone

The Northwest is a very fragile zone in the city with about 90,000 inhabitants, mostly low-income families. The neighbourhoods in this area are built upon 40 metres of mud and some of them have an elevation that is lower than the high tide experienced every week. Flooding generally occurs when soils have reached their carrying capacity and from increases in ocean water levels. In addition, the port of Santos was filled to a higher elevation to protect against tidal flow. This action resulted in trapping the water in the Northwest, preventing water from naturally flowing into the estuary. (ICF – GHK, 2012)

Dique da Vila Gilda

The community of Dique da Vila Gilda, one of the informal settlements in the Northwest zone, is located on the island of São Vicente on the border between the municipalities of São Vicente and Santos. It expands over a river, with houses originally built in the 1950s on the slope of a dike that keeps the river from flooding the island on which most of the city stands. Over the last 65 years the community perched itself on stilts above the murky Rio Bugre and became the largest slum area on stilts in Brazil with about 30,000 inhabitants.

This slum is a medical danger zone. Solid waste covers the water surface; there is no sanitation and floods occur often compromising the quality of drinking water. This informal settlement is destroying the ecosystem of the mangroves, which provides a wide range of ecological services.

Águas da Vila Gilda – Waters of Vila Gilda

The project Águas da Vila Gilda is tied to multiple environmental and socio-economic challenges, such as ecosystems rehabilitation, water pollution and lack of sanitation, climate change, lack of housing and the fragile social-economical context of slums.

The required system innovation to achieve adaptive housing in this estuarine area is an interesting opportunity to democratize technology, something that can empower people. Combining the forces of democracy with the solutions for climate change, the slum of Vila Gilda can reshuffle its system to ensure resilience and liveability.

Adaptive housing, as a matter of climate change, can safeguard people’s well-being in the re-urbanization processes of the Northwest. At the same time, climate mitigation can be increased when combining the design of adaptive housing with the rehabilitation of the mangrove ecosystem. This kind of forest has a huge capability of carbon sequestration. The recovered mangroves, as a matter of climate mitigation, give the people of Vila Gilda the basis for their new urban-ecological infrastructure: inspirational capital by passionate people, social capital by local employability and business, natural capital by biodiversity and also sanitation and energy supply. The circle is thus complete and the project’s mission is accomplished when the economic value of this strategy makes the return of investments possible.

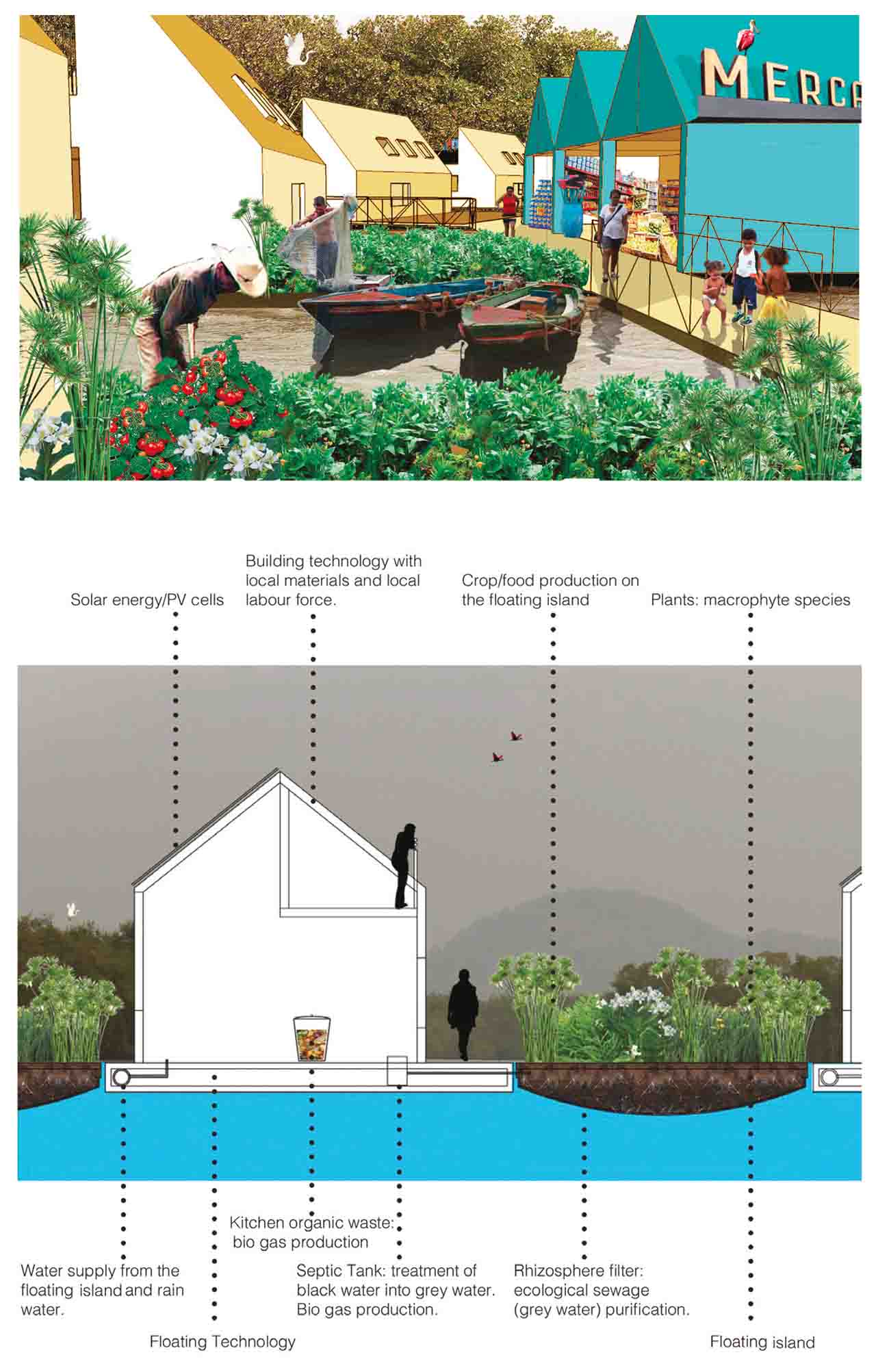

Águas da Vila Gilda is thus a neighbourhood-based concept for low-emission urban development incorporating solutions for adaptive housing. It proposes to house the slum inhabitants on a self-sufficient floating neighbourhood in the estuary of Santos in symbiosis with its direct surroundings, the city and environment.

The overarching goal is the enhancement of capacity for resilience of the slum population through climate adaptation and climate mitigation actions. The development of an inclusive and social-ecological plan, which adds economical value to the mangroves’ ecosystem services, is the main instrument to achieving this goal. The strategy ensures equitable use of environmental resources encompassing all of the activities of a city in a single model. Focusing on adaptive housing models, infrastructure according to the principles of circular economy, implementing clean energy sources and ecological sanitation, the project addresses the most critical environmental issues of Santos like ecosystem depletion, flooding events and water pollution of the estuary.

The innovative strategy of the project strongly contributes to the parallel development of Santos’s urban strategy regarding climate change and policies on sustainable urban development.

The resources produced by the mangrove’s ecosystem and the ecological services will be integrated in the project; services such as protection against floods, reduction of the riverbank erosion, maintenance of biodiversity, water filtering, the incubator for fishes and the capacity of mangrove soil to increase in elevation in response to local rises in sea level.

Bottom: Adaptive housing with selfsupporting infrasturcture, biological sewage system and clean-tech energy production

Behaviour change and commitment

Humans are affected by their surroundings, which can give us the conditions to make people feel more comfortable and safe. The collaborative and inclusive project approach aims to influence people’s behaviour engaging the inhabitants towards a sustainable lifestyle and, by doing so, assuring their rights to the city.

Since successful innovations come from a process where the people who will ultimately benefit from the results are given a voice in its development, the project empowers the local community by involving them in the building activities of their own local affordable infrastructure, creating employability and providing safe and adaptive housing. In other worlds: the project democratises technology.

The project’s approach builds capacity by helping the community to run and rule their lives by themselves. Initiatives to help stakeholders to obtain financing for their local and small-scale green economy business must have the municipalities’ attention.

And finally, the project works on education, making it comprehensive and personal thereby increasing the environmental awareness of the next generations in the transition to a sustainable community. The precious aspects contained in the drawings of the next generation of children will be safeguarded.

Comments (0)