From separation to transition

Urban edges advance a reflection on human territoriality and the capacity of remaking territory in relation to public spaces. This social territory making includes a set of appropriation and consequences of presence in public space. Urban edges are important elements in urbanism as existing territories, which give visibility to human-making activities and therefore bear indeterminacy of everyday life. Immaterial social relations that grow, meet and inhabit hard surfaces of cities, such as walls can affect their function and meaning: as the most common form of separation to be a place addressing the public. These material and immaterial relations have overlapping territories: urban boundaries, which are in constant transition. Unlike walls and edges that are interpreted to passively divide rules and norms between two environments, urban boundaries narrate never-ending stories of transitions between two or even more entities. Urban boundaries are places where everyday control and communication exchange are exhibited and where public and private, formal and informal, regular and irregular, proper and unusual are interwoven.

In the times we live in, physical separations and building limits have become controversial and cause heated debates in urbanism. On one hand, urbanism requires urban walls and edges, by which cities are shaped, functions are defined, and privacy is protected. On the other hand, urban edges like other elements in urbanism are subject to change. Urbanists are encouraged to consider the socio-spatial relationship of walls and edges and critically think of them as inclusive elements rather than as deterrents. Therefore, possibilities of socio-cultural appropriations of walls and edges are important factors in designing cities.

Such importance, however, has not been historically taken into consideration. Possibilities of appropriation reveal the ideologies behind public-private, formal-informal binary. Incidents show that appropriations were less of a concern among the cities than the aesthetic aspects and technical skills of building walls and edges. The meaning of urban edges as an element of separation is subject to change in history and in different geographies, which affects the physical form and materiality of walls. For example, urban walls traditionally performed for stability, thus being solid and opaque. Or in hot climates, urban solid and high walls were used to provide shade on the streets. Even though these impermeable walls were not designed to be welcoming for socio-cultural appropriations, as Image 1 shows, they have been adapted to everyday use. Some solid urban edges have been known to provide opportunity to support temporary economic exchange because the presence of these new and temporary activities would not block or threaten any existing businesses. At the social level, people also benefit from walls that protect them and allow them to watch others, while keeping them hidden and secure.

So, the separation of two environments has been one of the fundamental roles of urban walls. With the help of technology in material and construction, the form of walls has changed and become lighter and this has affected the typical meaning of walls and the sharp binary between public and private. For example, transparent facades are intentionally aimed at mirroring inside life to the outside world, while the norms and rules of each environment remains different. Depending on the design of ground floors, the life of such boundaries can be exchanged between the two environments. This connectivity and exchange along transparent walls, however, does not always welcome appropriation and invite ‘others’ to inhabit the edges. For example, there are several massive office buildings with no permeability or connection to the sidewalks around them. Even though walls are expected to function less as separation and more as inviting with the help of materiality, they are still built without consideration of their possibilities to become part of the everyday experience and appropriation.

Urban boundaries narrate never-ending stories of transitions between two or even more entities

There have been precedents in urbanism where the opportunity of exchanging public-private life along edges has been well appreciated. They show the potential of permeable facades and of extending inside life out. Most of these examples address appropriations as a set of socio-economic exchanges, usually between business owners and users. As Image 2 shows, based on the type of businesses, these edges support different public experiences. Some functions attract diverse groups to become users and some functions engage people through attractive sensual settings.

Appropriations, as socio-economic practices, are mostly limited to fleeting encounters, usually dominated by business owners who benefit from users’ spatial practices along the edges. The success of urban edges – particularly ground floors – as everyday places for social encounters and exchange has drawn the attention of business developers. As a result, we have witnessed in our cities how such experiences, have been reduced to patterns of consumption and, accordingly, privatisation of urban edges and lack of local identity (not to mention the birth of chain businesses with massive footprints).

The in-betweenness of urban boundaries

Traditional architecture, as mentioned above, has contributed to welcoming human experiences by emplacing needs along the edges. Semi-open corridors, covered and supported by buildings on one side, have different cultural reasoning in their constructions yet become a successful pattern for transforming passive building edges into public places. Porticos, porches, colonnades or Ravagh are examples of urban elements, which support human needs and a desire in public either to protect people from rain or hot sunshine, or to direct them towards certain places. These permeable boundaries support temporary everyday activities in public space such as waiting, making a phone call, sitting, loitering or watching others inconspicuously. These activities occur both in and without relation to established functions of the building. The norm of behaviour and use in these places is blurry and in-between public and private.

These boundaries, as Image 3 illustrates, are also popular locations for those temporary activities which require stability; something between permanent and temporary. For example, street vendors or artists need to be exposed to the public in order to attract them while requiring a location to settle and associate with their existence. Appropriation in urban boundaries sets an intangible territory that is temporary, therefore it is not perceived as a threat to formal and established businesses around them. Such in betweenness – in space, time and function – of apropriations reduces possible tensions among different stakeholders who are related to the urban edges.

Possibilities of socio-cultural appropriations of walls and edges are important factors in designing cities

Appropriations of urban edges, as other everyday practices, challenge formalities in cities. They manipulate physically urban walls, which are often considered as closed, passive or hostile objects. Appropriations also challenge the meaning of walls to be more than elements of separation and control in cities. The experience of ‘in-betweenness’, as mentioned above, is somewhere between public space and private space, confronting ‘strangers’ and the comfort of liberation. Appropriation occurs in such spatiotemporal conditions because it enables manipulation and makes change easier. So, they narrate stories of practicing the right of being in space and generating space based on need or desire, and also, stories of domination, expansion, control and taking over by those that have more power or privilege.

These spatiotemporal practices are political and poetical incidents in urbanism and metaphorical as a dialogue among its actors. Some actors are more dominant in such dialogue and impose their rules, while some are less visible. A careful observation can reveal such dialogue as passive-aggressive mechanisms along the edges, which highlight invisible actors and their materialised intentions imposed on other users. Instead of setting dos and don’ts messages, which address a group of people directly, there are many examples of personalising urban boundaries. Some of these appropriations are destructive if they indirectly provide an unwelcomed urban experience that causes others to leave the space.

Urban edges as zones of recognition and care

Urbanism plays an important role to assure diversity of use, wellbeing of users, as well as equality of opportunities along urban edges. Some urban edges, for example, might ignore the basic human needs in public. So, urbanism deals with humanising spatial experiences such as perception of safety. Some urban edges might delimit social opportunities such as encounters and togetherness and some might be exclusive to certain groups. Yet, urban edges are contested places in everyday life, where appropriations can be seen as a dialectical approach towards ignorance in the design of cities. Everyday urbanism is full of rich examples or alternative practices by which walls and edges become a medium for addressing users’ needs and rights to become public. Based on different contexts and cultures, urban walls are subject to manipulation while being manipulated. This socio-spatial relationship is constructed by the potentials of material edges but also by the users’ intention of becoming ‘public’: to be seen or heard publicly.

The ‘in-between’ characteristics of urban edges enable political expressions. Image 4 shows a wall in a NYC subway station that could mediate commuters’ peaceful expressions and thoughts written on Post-it notes. Initiated to promote reflection on the presidential election, ‘Subway Therapy’ was a kind of symbolic practice. Here, the wall has become a place for commuters to become agents of change. The wall is placed in-between their roles: they are both commuters and the public and neither of them. The subway wall acts as a boundary between them and those whom these messages are written for. Their appropriation as collective action allowed them to be seen and become ‘public’. When things become public, they are not private, invisible or personal anymore. So the urban edges can be true public spaces, which allow citizens to express their rights.

Some urban edges might delimit social opportunities such as encounters and togetherness

In-betweenness of urban boundaries has spatial, temporal and functional implications. The examples above show a few temporary ways by which urban edges could be used or contested to become more inviting and adaptable rather than being fixed objects of separation. Urban edges can be designed to trigger coherency of urban experiences at the walking level. There are examples in contemporary architecture providing empty spaces around the entrance of the building to be flexible and respond to urban needs. These spaces sometimes have in-between management where multiple regimes of control overlap. While there is a limitation for appropriation in these spaces based on what is ‘proper’ and ‘accepted’, there is also opportunity for those who would not experience these spaces otherwise. Studies show that designing ‘free’ spaces for flexibility and adaptation is not enough; something should be offered to the public to appropriate it.

In Sweden, based on a public land ownership strategy, all spaces are to be publicly accessible except urban blocks and water plus areas specifically marked for private purposes. High accessibility of urban spaces might increase perception of publicness yet not necessarily trigger appropriation and change. If spaces are physically accessible but not meant for everyone or for diverse activities, appropriations of space can be considered as destructive and lead to negative effects.

Therefore, it is not enough to design accessible surfaces to be flexible for public to use it. Those accessible spaces, which are for instance privately ruled and managed, or publicly invisible, target a certain group of users and limited types of appropriations. When others take urban boundaries to address their opinions, they engage the public in their struggles, at different levels of salience to consciousness. A good illustration of these types of appropriations is the HSBC building in central Hong Kong where migrants from South East Asia living and working as domestic workers for Hong Kong families gather. As Image 5 illustrates, they gather, sit on straw mats and do their nails and get their hair cut on the ground floor, which is open to the public; but such appropriation was never expected. Such in-between urban boundaries were taken up by minorities to meet, interact and help one another and, more importantly, to claim the space and feel at home. The government facilitated their needs after unsuccessful efforts were made to relocate them.

(Left) is publicly accessible and becomes a public space for domestic workers occupying it every Sunday (Right)

Appropriations of urban edges are micro actions, which reflect macro socio-economic issues in forms of alternative practice. Appropriations give recognition to the invisible public affected by these issues, such as homeless people in the least powerful tier of society. Urban edges should accordingly be seen as places of political discussions in urbanism by giving visibility to such issues and its affected groups. Practices of home-making or economic survival along the edges can be considered temporary based on the levels of public tolerance, or in other words, accepting informality in cities. In-betweenness of urban boundaries welcomes vulnerable actors and their appropriations, which would not be possible otherwise.

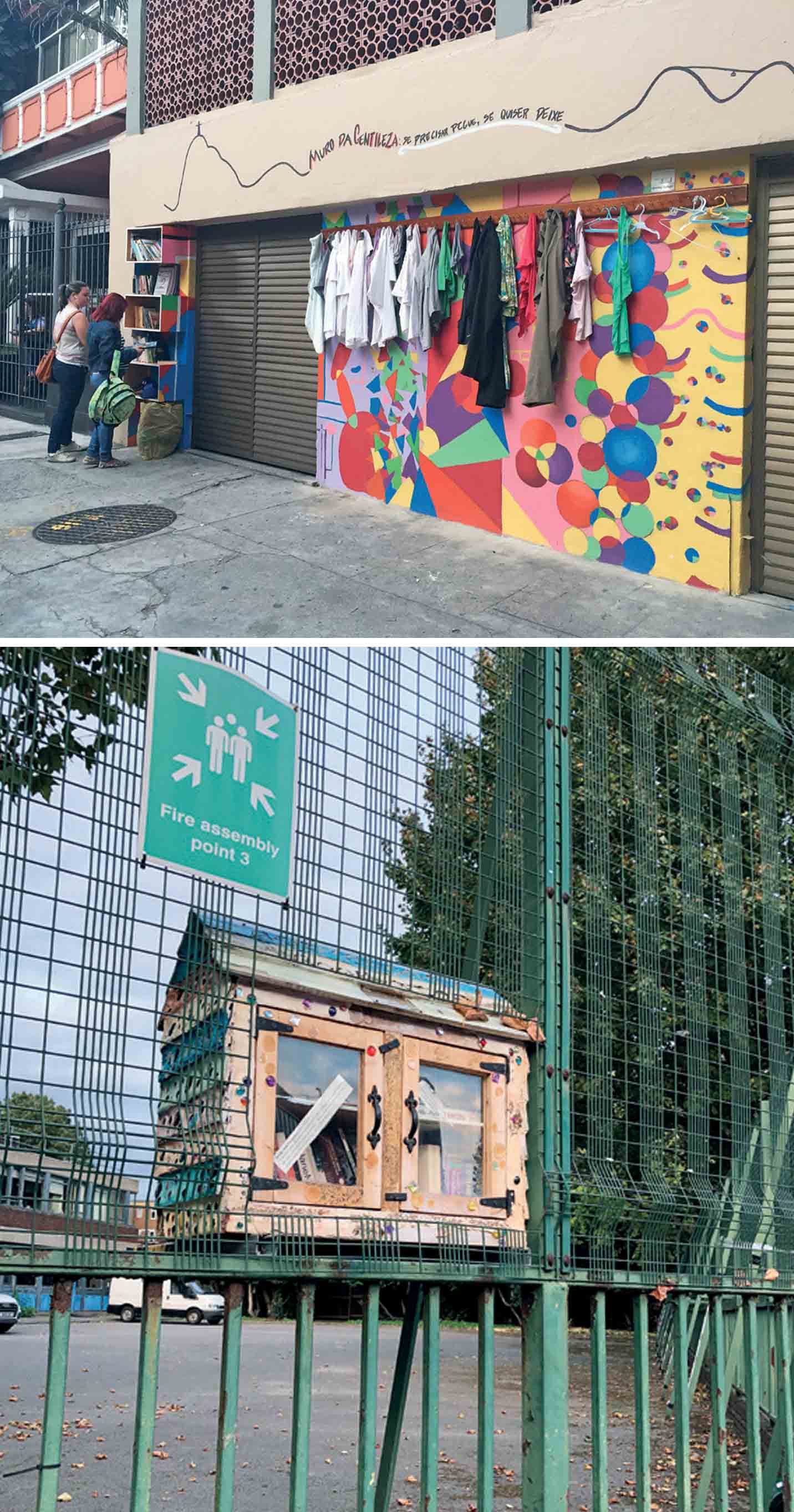

Urbanism can find and suggest urban edges with less sensitivity and higher possibility towards change such as the edges of massive urban infrastructure or empty plots waiting for redevelopment. Guiding temporary opportunities allows users to become creative and caring citizens able to transfer these territories as well as help lost spaces to improve. There are, for example, users’ appropriations of sidewalks and bicycle lanes to improve mobility and safety, which as a social construct, enhances social trust and the sense of community. Image 6 illustrates patterns of sharing and donating books and other items. Initiated in Iran and called the ‘Wall of Kindness’, this pattern started in low-income neighbourhoods where people offered clothes and basic things to homeless people. The ‘Wall of Kindness’ was socially mobilised and remained constant over time, stabilised and was even exported to other contexts and adapted to their needs.

Top: ‘Wall of Kindness’ (Rio de Janeiro). The message on the wall is: ‘Leave if you do not need, Take if you need’

Bottom: Common urban bookshelf (London)

As illustrated in Image 6, physical forms of edges play an important role, by which these vertical surfaces become truly public leading to sharing and caring. According to studies, people get a strong ‘sense of place’ when they practice in a place. Reiteration of these practices or, in other words, use of urban possibilities is the heart of what ‘place’ means. Urbanism offers many such opportunities, by which they can even empower people to become co-designers and appropriate the space according to their needs. So urbanism can strengthen the ‘sense of place’ by not only providing possibilities for people to use urban edges but also enables them to appropriate it. Urban edges then become playful and engaging public spaces instead of being a physical barrier.

In-between permanent and fixed legal territories, there are on-going manipulations, domination and contestations that give visibility to ignored ones, to unintended needs or to unexpected consequences. Appropriations address one of the crucial factors in urbanism, which is ‘time’. Urbanism should welcome change as an inevitable factor of everyday life; thus appropriation is considered progress. On a positive note, appropriation can be collaborative and inclusive. However, they can increase conflict and tension among different stakeholders along the edges and city planners could consider them a threat rather than progress.

Appropriation of urban edges has never ending possibilities. They are improvised actions that might challenge established territories, formal ownerships and control and the ordered image of a city. These manipulations, dominations and expressions, which cannot be fully and easily rationalised require smart and responsive urbanism to lead such transformation towards economic prosperity, political visibilities and socio-cultural engagements. Urban edges are then truly a public domain, reflecting equity, diversity and justice by allowing appropriations. Transforming urban edges to become inclusive places by designing opportunities for everyone to be visible and heard and even possibilities to protest against injustice, contribute to the liveability, democracy and inclusiveness of cities.

All photos: Elahe Karimnia

Comments (0)