Rotterdam is well known for its modern architecture and has a vibrant cultural scene with an eclectic variety of shops, restaurants and parks. It is home to Europe’s largest and one of the top ten most important ports in the world and from this naval and industrial heritage it is now emerging as an exciting and dynamic entrepreneurial hub.

PHOTO CREDIT: CITY OF ROTTERDAM

Center: Rotterdam promotes cycling

Right: Arnoud Molenaar, Rotterdam’s Chief Resilience Officer

Rotterdam also foresees new risks and 21st century challenges in the (near) future. For example: digitisation, climate change, the new economy, globalisation and clean energy transition.We know that we cannot become complacent and that these challenges need to be faced.

Rotterdam has a reputation for designing and engineering robust systems, but we acknowledge that future risks might call for a different response: more flexibility and greater inclusiveness, perhaps different governance and funding approaches.

We know that the technological and societal changes of the 21st century will present new risks and opportunities, but we want to fight for a sustainable, safe, united and healthy future for our city. In general, as we have entered an era of change, cities will have to develop a capacity to cope with disruptive transitions.

Cities that are resilient benefit from these transitions and are prepared for shocks and stresses that go with these changes.

Resilience in Relation to Climate Adaptation

In the last 10 years, Rotterdam has gained international acclaim for its work on climate adaptation. Our water squares, underground car parks with huge rain retention basins, multifunctional dikes and floating constructions are often profiled in the international press. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and Hurricane Sandy in New York, this knowledge has attracted millions of dollars of revenue for Rotterdam-based companies, which have a solid reputation for helping to climate-proof cities.

“We’re proud of our track record on managing water and climate risks, but we recognise this is only one of the stresses that our city is facing. Over the last two years, with the support of 100 Resilient Cities, pioneered by the Rockefeller Foundation, we have expanded our view of what city resilience means. We have begun to think of resilience in a much more holistic way, considering a broader range of shocks and stresses,” says Arnoud Molenaar, Rotterdam’s Chief Resilience Officer.

Right: Water storage Frederiksplein

Rotterdam is a delta city that lays 4-6 metres underneath sea level. In a worst-case scenario, water is entering the city from four directions: heavy rains, rising river, rising sea level and rising groundwater. “The construction of small and larger water storage facilities in the city combined with green areas like public parks and private gardens are definitely contributing to the resilience of Rotterdam. But we need to build on this, to scale up the benefits,” says Arnoud.

Clever water management approaches are as necessary as they are financially beneficial. Rotterdam works to better understand cascading impacts and to factor these into its cost-benefit decision making (e.g. prolonged power outage or cyber threat). The city will also strengthen its crisis management approaches based on increased knowledge of flood risks.

On a district level, the Zomerhofkwartier (Zoho) is a good example of urban water management. Together with the support of users of the area (residents, businesses, organisations and visitors) the neighbourhood has undergone a gradual urban regeneration. It is a neighbourhood, which previously had a lot of empty commercial units that have now been transformed into a vibrant district with 120 companies operating in the area. In addition, the unique multifunctional water square, Benthemplein, acted as a catalyst project for further development of the Zoho district.

Climate adaptation was the driver for sustainable development of the plaza and it has strengthened social cohesion.

The resilience office will collect experiences learnt in Zoho and scale them up to other districts and the surrounding areas. The district and wider region can therefore be used as an example of how to scale up green and creative solutions for water retention whilst also strengthening the community involved and building knowledge capital.

21st Century Infrastructure

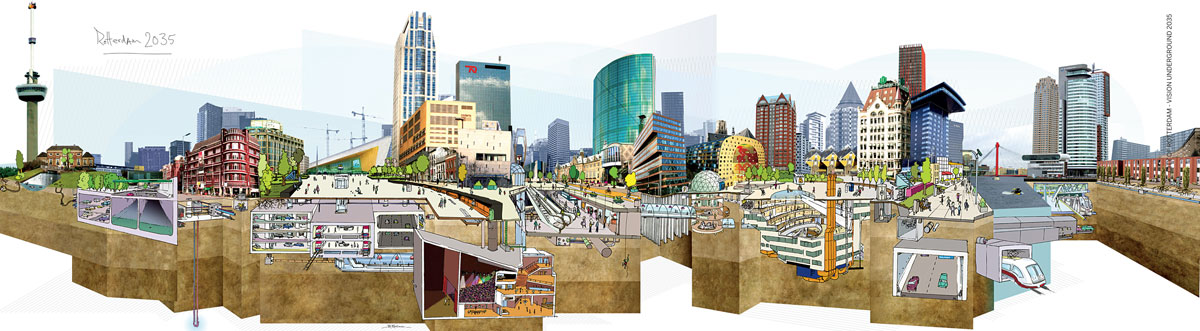

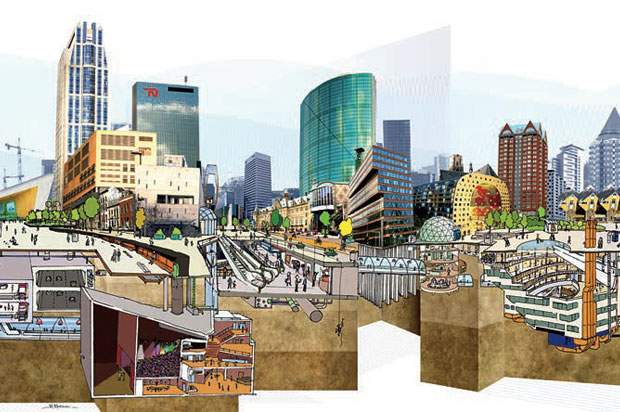

Rotterdam’s underground infrastructure is crucial for the city to function. The city is improving its old degraded infrastructure (e.g. gas networks and around 40 km. of sewer per year) whilst at the same time investing in new infrastructure that is fit for the future, for example, to support a clean energy transition and the next economy (digital).

Rotterdam’s underground infrastructure is quite robust, but lacks flexibility to respond to emergencies, new technological developments and above ground development growth is limited. This brings some risks related to repair capacity, delivery of sub-optimal solutions and poor integration of above and below ground services.

“We want to increase resilience by enhancing the awareness of risk, developing a policy for more robust decision making with a more integrated planning practice both underground and above ground, relating to infrastructural interventions. This requires a reinforcement of cooperation among all infrastructure managers, including the city as a platform to share plans and (often confidential) knowledge and information. We aim to create more specific databases and information on the location of infrastructure and functions and interdependencies of the subsurface. We will also explore how innovative SMART technology can be integrated into the ‘Street of the Future’. Our resilience strategy is committed to action in each of these areas,” asserts Arnoud.

Rotterdam’s asset management team maintains and manages all assets in public spaces as well as a risk register. This includes items such as bridges and quay walls, as well as green spaces and lighting.

Asset management not only considers the costs and current status of the assets themselves, but also the potential risks that the failure of the assets could have on the functioning of the city.

By mapping the risks, decisions can be made as to what measures should and should not be performed based on a balance of performance, risk and cost. Smart investments now can often deliver savings in the future. This programme will develop protocols for the asset management of underground infrastructure, by including resilience as key quality, intended to support decision making in respect of maintenance and replacement.

Bottom Left: Social use of rooftops

Bottom Right: Residents of Rotterdam become suppliers of energy

Generally, risk management and spatial planning do not consider the costs and benefits of development in the longer term (i.e. the full life cycle considerations), but this could support effective decision-making and help make the case for investment in redundancy. This is particularly prevalent in the context of underground critical infrastructure.

Rotterdam is preparing holistically for future and possible shocks. An important part of the National Delta Program is the concept of ‘multi–layer safety’. This involves prevention (1st layer), spatial adaptation (2nd layer) and evacuation (3rd layer). The evacuation layer has yet to be fully planned and developed. The pilot study, ‘Crisis management during floods’, found that vertical evacuation needs proper consideration as a serious option for layer 3. Specifically, consideration should be given to the fact that the highest areas are located along the river, outside the dikes and the entire port area. Rotterdam will develop a vertical evacuation plan as part of the resilience strategy implementation.

Energy Transition

Rotterdam wants to be the front-runner in the clean energy transition and supports the agreements through COP21 in Paris. The appetite for, and evolution of, sustainable energy technologies will have a great influence on the city and the port of Rotterdam.

“We are striving for a diversification of energy sources and to make the urban energy infrastructure more flexible, in order to successfully deliver this clean energy,” says Arnoud Molenaar. He adds, “Delivering this transition is a large and complex task, but it provides the opportunity for Rotterdam to strengthen its economy and reputation.”

A transition to renewable energy requires – in addition to building-related efficiency measures – a supporting and flexible infrastructure.

The city realised that moving this from ambition to reality is challenging and will require an integrated strategy. This strategic plan will outline options, costs and benefits and set out a preferred strategy. It will consider technology innovation, phasing, emissions and infrastructure flexibility, like for example the ‘heat roundabout’, which uses waste heat from the port district to warm up households in the entire region. This is a flagship project for Rotterdam and the city will collaborate on this with other cities within the 100 Resilient Cities network.

The current and planned activities of the port of Rotterdam (Bioport), the roadmap Next Economy for ‘a zero carbon’ future (Smart Energy Delta) and the measures of Rotterdam’s sustainability programme focused on renewable energy and energy conservation all support this agenda.

New actions are underway to underline the urgency of this transition. The Rotterdam energy infrastructure plan is a strategy for energy diversification at a district level, each with a roadmap for implementation. The port-industrial cluster will make and carry out an action plan in a joint effort with industries, the government and the Rotterdam Port Authority.

CITY OF ROTTERDAM - VISION UNDERGROUND 2035

Cyber Resilience

The digitisation of society offers many opportunities, but it also brings risks of disruption of essential processes for production, logistics and services. While the investments in cyber technology increase at a rate of 27% per year, the investments in cyber security only increase at a rate of 4%. The necessity of a cyber resilient port of Rotterdam was recognised by the Mayor, Chief Prosecutor and Chief of Police in 2014. Together with the Rotterdam Port Authority and Deltalinqs (representing 700 companies), they have ordered a strategy on cyber resilience.

The resilience of Rotterdam to cyber threats will increase by joining forces to improve responsiveness and ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) products, enhancing awareness and sharing knowledge. Both the port and city are taking cyber security seriously. They have worked with Microsoft to develop comparable strategies and actions comprising 15 building blocks including a Cyber Resilience Platform, Cyber Resilience Desk, Cyber Resilience Co–op and a Port Cyber Resilience Officer.

“It is fundamental for Rotterdam to have a Delta plan for Cyber Resilience,” states Arnoud adding, “Luckily, we are not alone in this; we get support from the federal government and specialised private sector companies. In addition, we collaborate with cities like London and Singapore on actions that we can take to increase cyber resilience. Rotterdam aims to have implemented its cyber resilience strategy within the next 5 years and will have significantly enhanced its cyber resilience.”

International City Network

The 100 Resilient Cities network is dedicated to helping cities around the world become more resilient to the physical, social and economic challenges that are a growing part of the 21st century. Within this network, cities work together on resilience topics and related challenges. In October 2015, Rotterdam organised the first city exchange event ever, focusing on water and climate resilience. The city of Surat participated in that exchange, which recently was followed up by an official visit to Surat to explore the challenges and the way Rotterdam can help the city of Surat. Both cities succeeded to find European funding to finance the process of collaboration.

Partners like Deltares and Arcadis Rotterdam will support Surat with knowledge development and capacity building on integrated water management and climate resilience. Also, the possibility of whether Surat can benefit from things like the Rotterdam Adaptation Academy will be explored, as well as the Global Centre of Excellence on Climate Adaptation, which will be hosted by the city of Rotterdam partnered by the UN, as announced during the COP23 in Bonn.

Comments (0)