“A plan arranges organs in order, thus creating an organism. The organs possess distinctive qualities: lungs, heart, stomach. I am claiming Sun, Space and green surroundings for everybody and striving to provide you with an efficient ‘Circulation’. The great new word in architecture and planning.” — Le Corbusier, the architect of Chandigarh

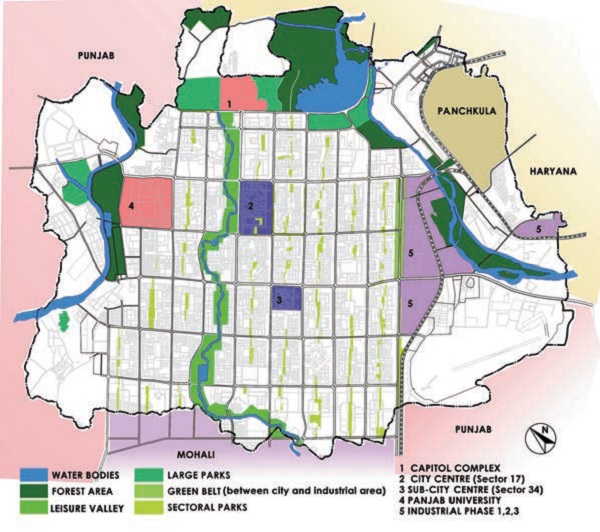

India has the largest species of flowering indigenous trees, which serve for micro climatic amelioration and for embellishing the urban landscape of towns. In the urban planning of the 20th century, Chandigarh is one of the best-known examples not only for planning, but also for its landscape design at various levels. Its Master Plan is a unique work of art that laid the foundation of what is now popularly called the City Beautiful.

Original Character of the Site

For Chandigarh, the site had its own inherent potential, which allowed the setting of the city with a continuation of a relationship that existed between man and nature. It was located at the foot of the Kasauli Hills that served as the dominant visual element. The topography of the site manages the natural surface drainage. It is bound by two seasonal rivulets, Patiala ki Rao in the northwest and Sukhna Choe in the southeast, which carry the rain water runoff that descends from the hills. Through the heart of the city a seasonal nullah runs through the Sukhna Gorge. Existing clumps of trees have been preserved at various points to make a unique linkage with its roots and create ‘an illusion of age’. To demonstrate the garden city idea, Le Corbusier designed Chandigarh so that at ground level people can interact with the vast landscape. In Chandigarh, where the climate is composite, multi-storeyed residential flats are not comfortable unless they are air-conditioned. Therefore, Chandigarh was planned partially vertical and partially horizontal by erecting two-storeyed residential buildings whereas the offices comprise four to six storeyed buildings. Instead of mechanical methods, natural shading, orientation of buildings and passive means of cooling and aeration were adopted. Going a step further, the Tree Plantation Order of 1952 laid the early beginning for a green cover, which residents experience and deeply appreciate today.

The idiom of ‘Sun-Space-Verdure’ (body and spirit) is also visible in the planning of the city. Le Corbusier believed that man couldn’t be healthy in body and spirit if the natural environment is isolated from him. Therefore, special attention has been given to the care of body and spirit by integrating the areas of recreation and intellectual leisure with the mundane functions of working and circulation.

An overall vision for the Urban Landscape of the city was set out with respect to the setting and site incorporating the seasonal rivulets, Sukhna Lake and the periphery greens. Leisure Valley is a natural gorge and lung for the city through all the sectors from north to south. The landscape along VS – V1 to V7 with a tree plantation plan provides canopies for cyclists and pedestrians as well as tunnels of shade for motorists.

At the urban level, the Capitol Complex serves as a focal point for the city and as a ceremonial axis leading to the hills. The focal point of the city was to be the Capitol Complex, which was sited on the northwest side at the upper edge of the city, thus permitting a view of the mountains. Le Corbusier separated the government buildings from the city, since he wanted to express monumentality.

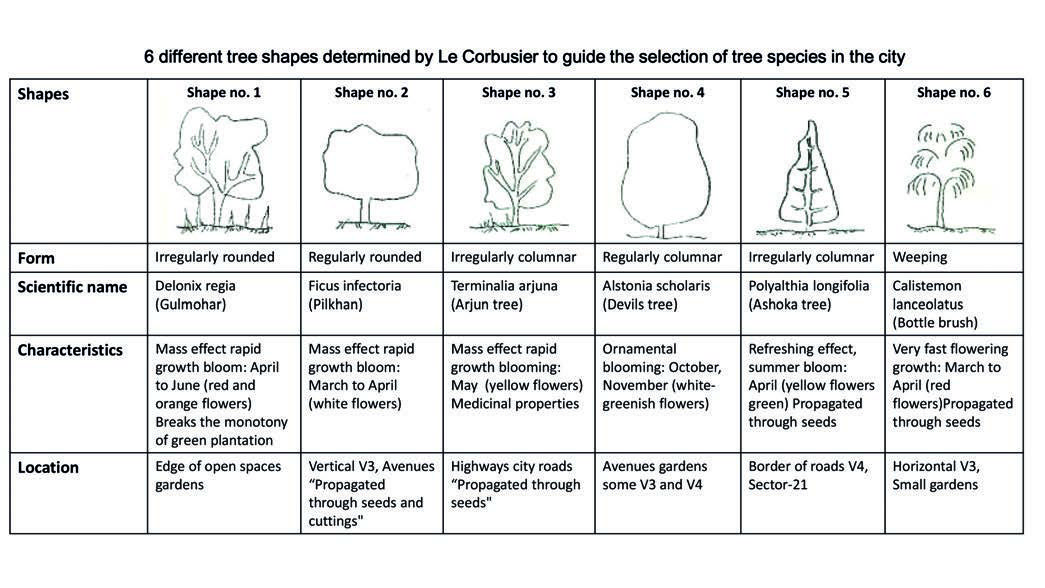

Therefore, he proposed a continuous horizontal embankment to block the view of the Capitol from the city while bringing the distant landscape into focus. He proposed a Ha-Ha wall at the village side to prevent the cattle from grazing into the Capitol, at the same time permitting an unobstructed view of the Shivalik Hills. A landscape advisory committee was set up under Dr. M.S. Randhawa, the first Chief Commissioner of the city. A grand planting scheme was envisaged to include urbanistic elements, tree selection based on shape and character, blossom colours and varieties (evergreen and deciduous).

Le Corbusier adopted urban greenery to bridge the gap between citizens and nature. He designed open spaces at many different scales as well as in many different forms to retain the identity of the concept, as it would help in making the city beautiful. On the city scale, these open spaces include urban forestry. Chandigarh has 3245 hectares of forests and most of it is hilly. The forest areas are mostly around Sukhna Lake, Sukhna Choe and Patiala ki Rao. To discourage the development of villages or sprawl around Chandigarh, a green belt was developed within a 10 km limit beyond the city under the ‘Periphery Control Act, 1952’. Winds over the two choes running on the Eastern and Western periphery brought sand and dust over to the city site. In order to protect the city from these sandstorms, a dense tree plantation was carried out on both sides of the Sukhna Choe and on the left bank of Patiala ki Rao. These dense plantations are now a part of the city forest.

Another change carrying forth Le Corbusier’s ideas of landscape is the development of large swathes into parks, which serve for city-level recreation as well.

Large parks

Ample area has been provided for parks. An informal style of planting has been used so that it may intermingle with old trees. There are recreational areas such as a Botanical Garden, Butterfly Park, Shivalik Arboretum, Peacock Park, Rajendra Park and Rose Garden.

Water bodies

To prevent flooding from the hills during the monsoons, Le Corbusier designed the Sukhna Lake in 1958 as a gift to the citizens of Chandigarh.

It is one of the major recreational zones of the city today. The lake is fed by water from the catchment area of the seasonal rivulets on the foothills of the Shivalik. Sukhna Lake provides an escape to the citizens from the routine of city life and allows them to enjoy the beauty of nature in peace and silence. Sukhna is also a sanctuary for many exotic migratory birds. Sukhna Lake is on the list of Heritage Precincts shortlisted for heritage status. Today, Chandigarh has added two more lakes: the New Lake and Dhanas Lake on the southern and western end of the city.

Green belt (within the sectoral grid and towards the industrial area)

Leisure Valley is a continuous, 8 km-long parkland with various theme gardens running along the seasonal rivulet N-Choe. It provides an opportunity to the citizens to move through the city in a continuous band of various theme gardens. It was laid in free open spaces either single or in homogeneous groups, or in heterogeneous groups, or in large forest plantations. The significance of this parkland is not only of environmental and ecological value, but it also has enormous aesthetic value. Due to interruption of existing V3 and V4 road links of various sectors on the surface level, it’s difficult to maintain a pedestrian link. To withstand industrial pollution and to separate the residential from the industrial area, a mango belt having 10-12 rows of trees was laid along the Purv Marg. But this belt is too narrow to act as an organic barrier against the smoke and fumes and with the increasing traffic this belt falls short of acting as the organic barrier aganist industrial pollution.

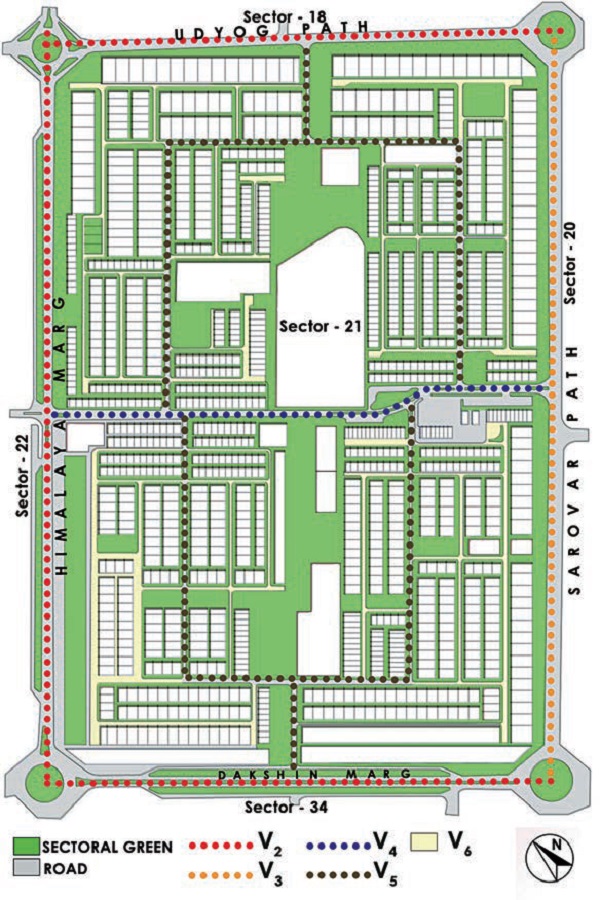

Green belts along circulation spines: A hierarchical system

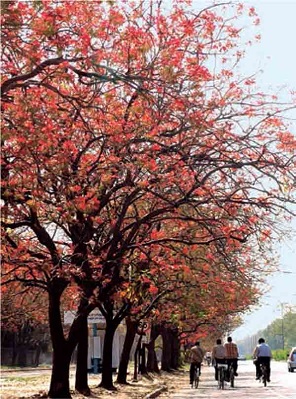

Les Sept Voies or 7Vs ranging from V1-V7 distribute traffic from intercity right up to the dwellings. To retain the original topography of the site, a gridiron regimen was followed for the road network that forms the skeleton of the city. Along roads, single, double or multiple rows of tree plantations were planted depending on the location, type and orientation of the road in relation to the sun. It serves as a complimenting patina of greenery to the road network of the city. In order to enliven the grey scale of concrete facades and to emphasise the architectural elements, rows of trees provide ample shade to those waiting at bus stops, bicycling, etc.

V2’s are along the Capitol Complex, Madhya Marg and Jan Marg. The Avenue of the Capitol serves as an automobile highway with a band of parking, a large pavement on each side and high buildings. The road is planted with high trees to demarcate the roadway and there is a variety of shady trees for the pedestrian area. On a sunny day, it is a relief to walk along the shady pedestrian paths, as fast traffic regulates the V2 Capitol leading to the World Heritage Site: the Capitol Complex.

V3’s and V2’s receive and convey high-speed traffic and define sectors. There are two directions of V3’s: horizontal, which is parallel to the station avenue and V2 vertical, which are parallel to the avenue of the capitol. Vertical V3’s would be bad in winter when the summer sun is low on the horizon.

Therefore, evergreen trees with large umbrellas like crowns such as Ficus infectoria (Pilkhan), Chukrasia tabularis (Indian Mahagony) etc. have been planted, which also create tunnel effects. In summer, the sun is almost at its zenith in horizontal V3’s. Therefore, trees with light foliage such as Alstonia scholaris have been planted.

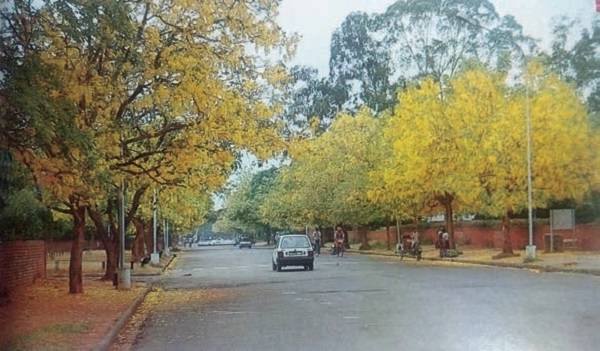

V4’s are the market streets where the most intense activity of urban life of the sector is witnessed. Each sector V4 is planted with flowering trees having different colours such as red, yellow, magenta, which give character and identity to each sector. Flowering trees on the V4 not only beautify the avenue, but they also serve to educate the public in good planting practices.

V5 and V6 reach the doors of the dwellings. On the V5 road, a single row of evergreen trees with a combination of flowering trees were planted on one side of the road to break the monotony of the built form. Masses of blossoms enhance the architectural features of buildings arrayed along V5. For example: Chukrasia tabularis (Indian Mahagony) and Cassia fistula (Amaltas), Cassia nadosa, Cassia javanica, Bauhinia purpurea (Butterfly tree), Bauhinia variegata (Kachnar) planted in Sector 23. On the V6 road – keeping in mind the direction of the sun, location and height of the houses – deciduous trees such as Lagerstroemia thorelli (Saona), Lagerstroemia Flos-reginae, Lagerstroemia Rosea, have been planted.

Micro level

Within the sector, which was the container of life according to the designer, several parks and green belts continue to connect residents and nature. Linear park belts running from the northeast to the southwest of the residential sectors are provided for local recreation and as sites for school and community buildings. These linear park belts are called Sector Greens and they provide an uninterrupted view of the mountains from all parts of the city. To create an illusion of great age, clumps of trees such as Date palm, Flame of forests etc., were retained as well as exotic and indigenous trees planted with the existing ones.

Le Corbusier’s ‘green city’ has inspired people to nurture plant life. There are very few houses without a tree. The open spaces in residential units were introduced in such a way that they look like the extension of the home and residents enjoy the essential and free joys of life: the sun, space and verdure (greenery).

Some small parks have been located between clusters of houses, to be used by the residents for social and recreational purposes. The layout of houses has been made in such a manner that the view of the Shivalik Hills is not obscured even at ground level. In the first phase, the height of houses was restricted to three floors so as to provide unhindered views of the hills.

Today’s scenario

Today, Chandigarh has grown beyond expectations in terms of population. As per the Census 2011, Chandigarh Union Territory has a population of 1,054,686, which is more than twice that of the number for which it was originally planned. By 2021, the population of Chandigarh is projected to be around 19.5 lacs (at current rate of growth) almost four times more than for the number it was originally built.

As far as the open spaces are concerned the issues at hand are:

1. Unplanned rapid urbanisation and encroachment in the surrounding area of choes is not only destroying the ecology but also polluting the sub soil water.

2. Rampant unregulated sand mining in Patiala ki Rao is also threatening the water recharging capacity.

3. The concept of open space network has not been carried forward in phase II and III of the city. The quality and nature of open spaces has faded away due to encroachment or disregard to the building byelaws. At several places, the street width is compromised with one side taken for parking, due to lack of parking space and poor enforcement.

4. Chandigarh has the highest ratio of per capita ownership of cars in the country. Due to this, a large number of open spaces have been encroached upon for parking cars.

5. The linear park running from the northeast to the southwest is not interconnected as per the conceptual plan.

6. The Chandigarh Master Plan 2031 shows an analysis on availability of open spaces within the city and sectoral grid, which clearly shows that in 2031, the open spaces may have a shortfall of 23.55 acres.

To overcome this, the Chandigarh Green Action Plan and Chandigarh Master Plan 2031 have worked to conserve this strong relationship of citizens to the city against the growing challenge of the phenomenal growth and the population upsurge, which has gone far beyond its planned capacity. This has been achieved through enhancing and augmenting the rich, diverse and surviving greenery.

|  |

In the 21st century, we can say that the city plan of Chandigarh has methodically evolved with a hierarchy of open spaces, landscape areas, recreational areas etc., which are well distributed over the city. Unlike other Indian cities, Chandigarh doesn’t have any random leftover spaces as open spaces, but rather a well-planned orderly structure. Open spaces, in terms of the original concept of the Green City are the soul of Chandigarh and must never be stifled by thoughtless additions of buildings, roads and infrastructure in the future. The three planning postulates of Sun, Space, and Verdure should always remain our directive principle. In the past few years, steps have been taken to retain the character and soul of the city, but there is an urgent need for a detailed and differentiated master plan to safeguard the landscape design of the city. Thematic studies to understand and retain the character of the primordial landscape, waterways and topography can enhance and preserve the character of the landscape design and morphology of the city. Government initiatives and enforcement mechanisms cannot alone fulfill this agenda. The responsible role of citizens, youth and children must be initiated to nurture the city’s treescape and conserve its landscape character.

The Chandigarh Master Plan 2031 has strongly protected the existing green cover, water catchment areas and recommended the eco-sensitive zone (Sukhna Wildlife Sanctuary, Sukhna Choe). The City Reserve Forest is another protection layer to the inspiring greenscape of the city. The zoning plans of sectors are to be maintained so that no other land use except those associated with the parks comes up in the open spaces.

Bibliography:

Administration, Chandigarh. (2031). Chandigarh Master Plan- 2031. Chandigarh.

Randhawa, M.S. (1965). Flowering trees. National Book Trust.

Singh, C., Wattas, R., & Dhillon, S. H. (1998). Trees of Chandigarh. New Delhi: B.R. Publishing.

Comments (0)