Australian cities have a relevance to their Indian counterparts because they are both large, relatively dry countries that extend from tropical to cool temperate climates. Australia even has limited alpine areas though they are only a pale reflection of the much younger and grander mountains along India’s northern boundary.

Our cities are young compared to India’s, being largely of low density and developed mostly in the era of the car. The population is also tiny compared to India’s, though the larger cities, especially Melbourne and Sydney, are growing rapidly and starting to develop areas of high density.

Limited water and the increasing effects of climate change have encouraged consideration of what needs to be done to develop our cities so they can maintain and enhance their liveability for future generations. They also need to dramatically reduce their carbon footprint if we are going to help the world meet the carbon reduction targets set in Paris.

You might ask how urban trees and greening are relevant to these discussions when there are so many more obvious planning, engineering and economic factors at play.

Finding space for trees to be planted and thrive is becoming more difficult and at the same time more important for the well-being of people and the environment

The landscape design and management professions have long argued the value of good design and the need for parks and trees in cities, but they have tended to be treated as optional, decorative additions, ‘the icing on the cake’, that is all too often cut as funds run short when large infrastructure and other construction projects near their end. Nevertheless, these professions and the green industry have developed from small beginnings in the 1960s to become quite influential through their completed projects and growth.

Open space and natural bushland areas are theoretically protected by land-use controls but they are often sacrificed to accommodate transport infrastructure or other development as cities and towns grow.

Landscape professionals include planners, designers, arborists, horticulturalists, engineers, consultants, academics and government policy and landscape maintenance staff. Then there is the industry that grows and supplies plants and contracts to build and maintain the landscapes within cities, towns and conservation and tourist areas.

This is the ‘green industry’ that has come together to develop and promote their shared vision of 20% more and better green space in urban areas by 2020.

Since 2013, it has grown into a network of more than 400 member organisations and individuals and has collaborated on a range of projects that provide the tools, resources and networks necessary to achieve this common vision.

Why do we need to green our urban areas?

The benefits of trees in cities have been understood since cities began. Gardens have always been part of cities for food and recreation and most cities have streets lined with trees that enhance their status and property value.

Modern cities are becoming more complex, denser and the impact of transport and other services like power, sewerage, drainage and communications is working to diminish the qualities that make cities liveable from the perspectives of health and psychological well-being.

Finding space for trees to be planted and thrive is becoming more difficult and at the same time more important for the well-being of people and the environment. We are just beginning to realise their benefits to the economy because the cost/benefit of trees is not as easily quantified as other major investments in the development of cities like new buildings, roads and services. The costs and benefits are often accrued over many decades and some are hard to predict such as those connected to climate change.

Green space in modern cities is good for the economy, for the well-being of residents and for the environment. Surveys of Australians show that a large majority value green space for their psychological health and enhanced productivity. It is also believed that access to green space increases quality of life in old age and extends lifespans.

Green space in cities is also considered to be important for the development of children, enhancing their mental and emotional health and improving their behaviour. Parks and streets that are green enhance social connections through safe, informal and organised use of these spaces.

The value of trees and vegetation in Australia’s larger cities is now being recognised for its quantifiable contribution to clean air, the management of storm water and the amelioration of excess heat that has caused deaths during heatwaves. Trees and landscape can also enhance the energy efficiency of buildings.

The impact of climate change during the coming century is becoming better understood as a serious challenge. Greening of cities is emerging as a key opportunity for enhancing the resilience of cities as climate change increasingly kicks in.

Understanding what is happening to vegetation in urban Australia

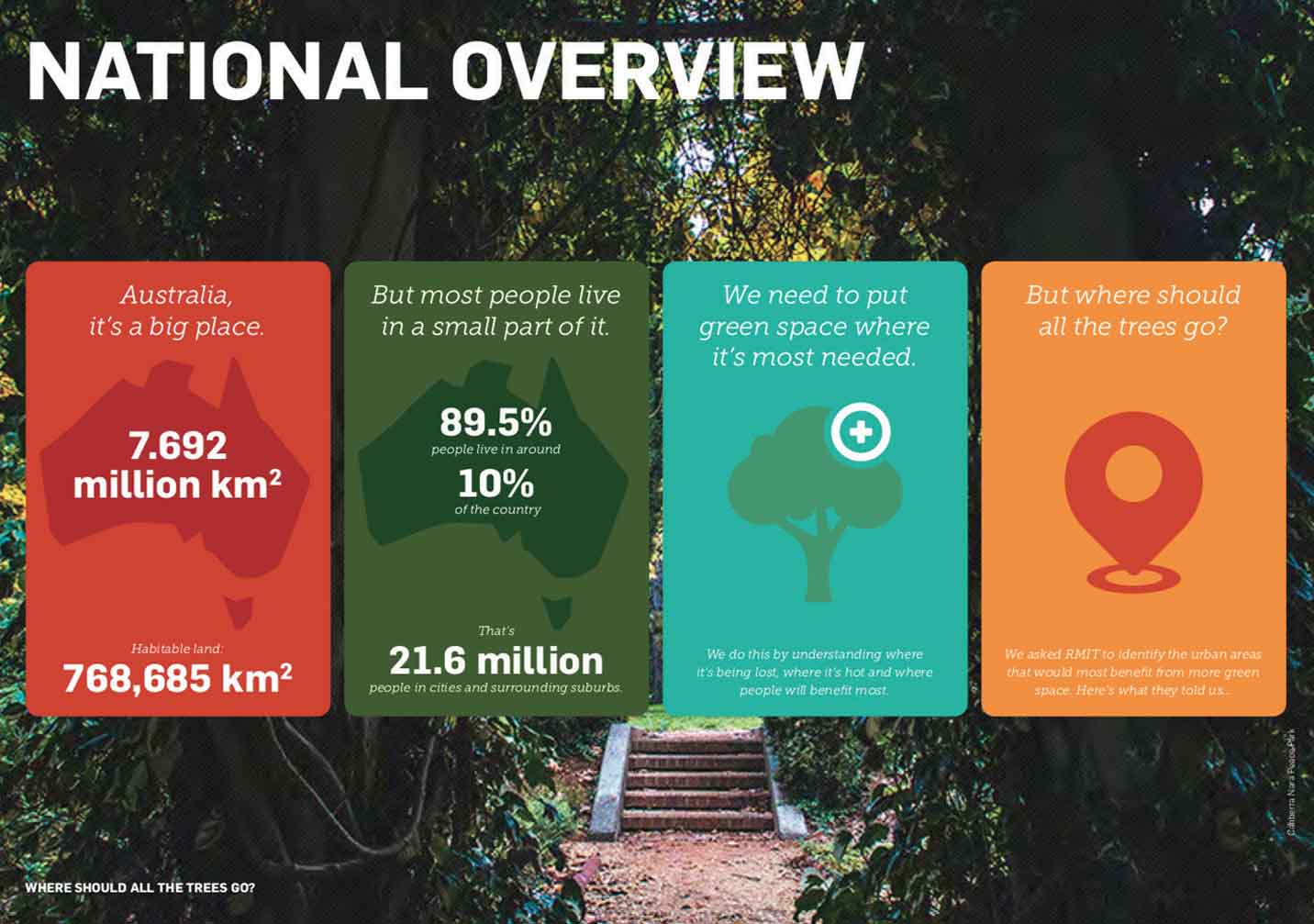

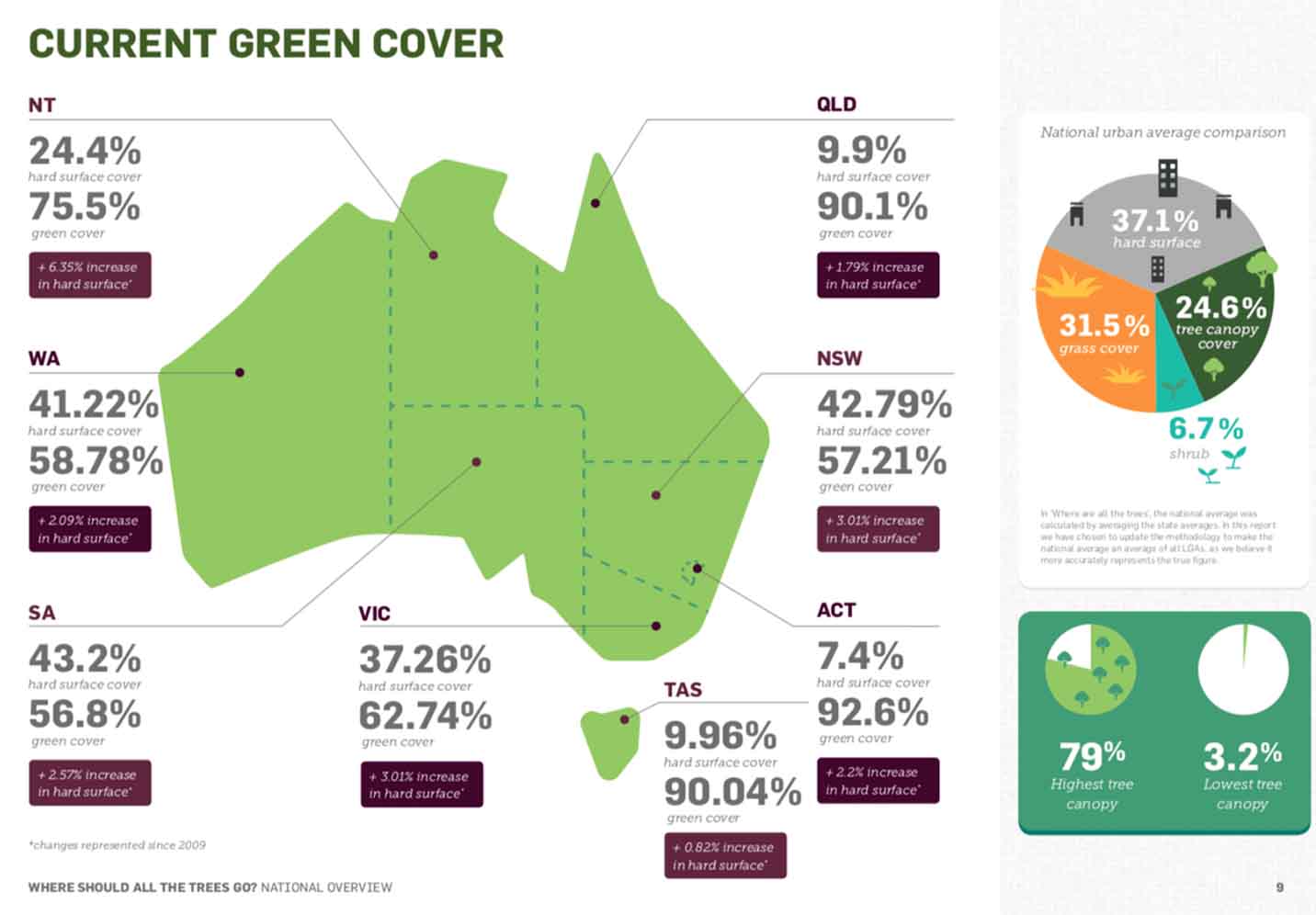

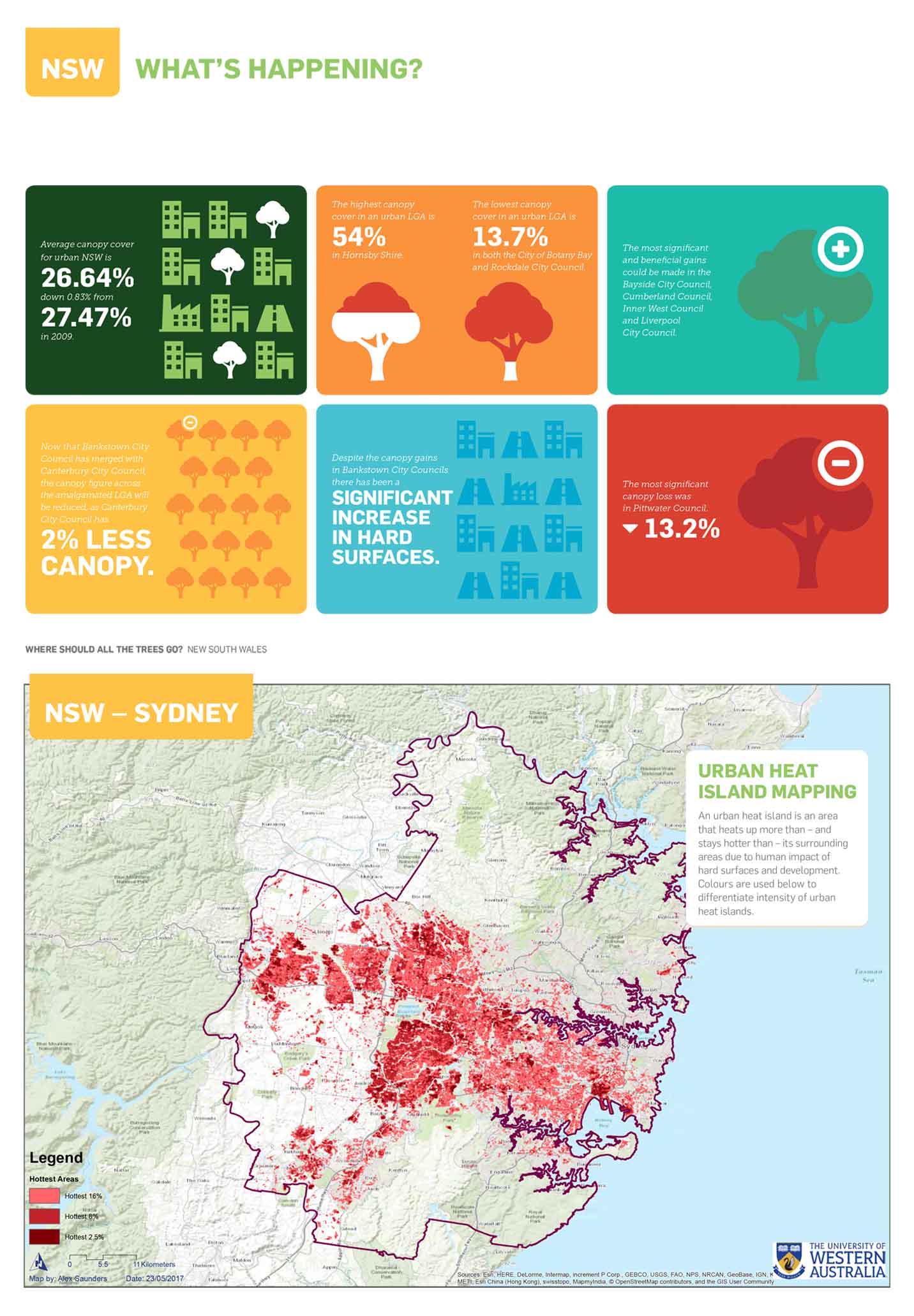

An important element of the 202020 Vision is benchmarking of tree canopy cover as well as grass and shrubs versus hard surfaces in Australian local government areas using the free American Forest Service i-Tree software. The Institute for Sustainable Futures at the University of Technology, Sydney, has customised this software for Australian conditions. It uses satellite images to measure changes in vegetation cover of urban areas between 2013 (Institute of Sustainable Futures) and 2017 (RMIT).

In addition, a vulnerability index – Vulnerability to Heat, poor Health and Economic Disadvantage (VHHEDA)–has been developed by researchers at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology to suggest where greening is most needed in cities.

This work gives some benchmarks and a way of monitoring progress towards achieving the 202020 Vision. The findings are reported in detail in the report Where Should All The Trees Go?, available for free download on the research hub of the 202020 Vision website.

Urban forest strategies

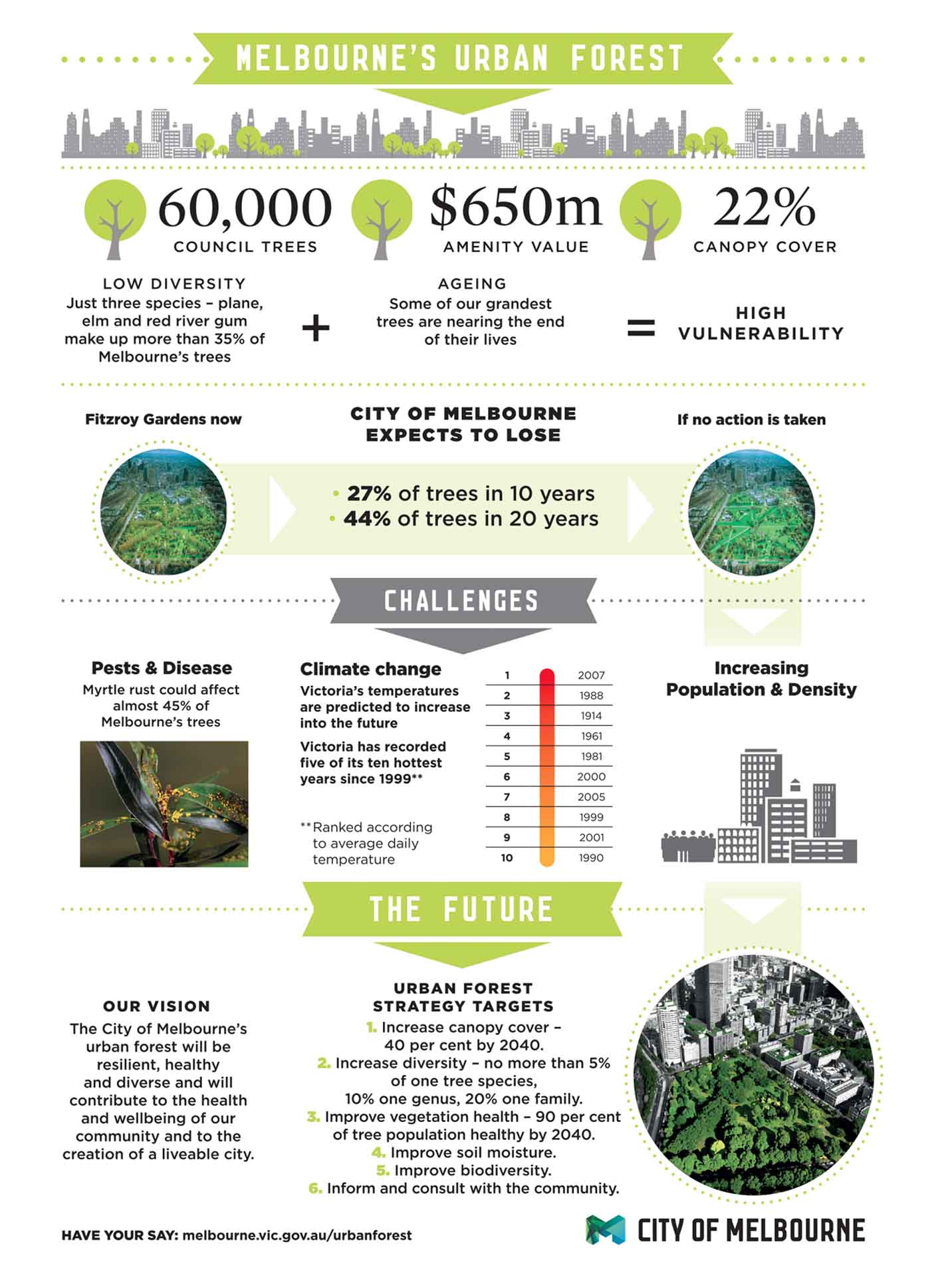

The City of Melbourne led the way with the development of Australia’s first Urban Forest Strategy in 2012, which examined the issues of vegetation within the central city, setting out clear objectives for the future as summarised in this infographic.

This has been followed up by community consultation and detailed planning for greening the city precinct-by-precinct. Heat mapping at a street-by-street level and evaluation of the health, condition, safety and economic value of all existing trees has enabled informed decisions about the priority and nature of works planned in the coming budget periods so the community can track progress.

Melbourne has also researched tree species to understand how they will perform over their lifetime under climate change scenarios. 202020 Vision has built on this work by producing an Urban Forest Handbook that has in turn led to many municipalities making a start on this type of plan.

|

Urban trees and water

Australian cities were traditionally designed around the idea that rainfall from pavements and roofs should be collected in pits and piped off to the nearest stream, river or ocean. This was considered the most efficient and healthy solution, but as cities grew and were more intensively redeveloped, the costs of developing and maintaining these systems increased and now urban flooding is an increasing risk.

During the same period, trees were planted where they could either survive on year round access to ground water or through artificial irrigation with treated water from the water supply systems. Many trees have declined or been removed as more pavements, services and buildings are built. Planting and maintaining new trees has become more challenging and expensive because of competition for space. Large areas of natural vegetation have been cleared to accommodate development of roads, industry, services and new suburbs.

In recent decades, the limits to the availability of cheap, treated water has been reached in many cities causing the introduction of water restrictions and the need to develop ever more expensive supplies of water through dams and desalination plants.

Climate change will lead to increased droughts, periods of life-threatening high temperatures and the converse problem of more storm and flood events.

Trees and other green spaces, including roof gardens, are seen as important to the continued liveability of cities as they develop and climate change modifies the weather, but how can they be developed and maintained as cities become denser and more complex?

One key opportunity is the harvesting and better use of urban storm water that currently goes to the rivers and ocean, often in a polluted state. Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) is a new field of stormwater engineering that is developing strategies to capture and naturally treat urban storm water close to where it falls as rain. This can reduce urban flooding and return water to the soil where it is needed to support vegetation including trees.

This concept is promoted as ‘blue meets green’ with the idea that cities need to think of water and vegetation together as one system and integrate this approach throughout cities when retro-fitting is established or while developing new, urban areas.

Trees and other green spaces, including roof gardens, are seen as important to the continued liveability of cities as they develop and climate change modifies the weather

Planning and funding for blue and green infrastructure needs to be provided by all levels of government along with other major infrastructure like roads, public transport, sewer systems and housing as part of city development.

There has been much experimentation and construction of innovative WSUD projects in Australian cities over the last decade or two. These projects include water harvesting and storage for reuse, daylighting of piped stormwater to recreate natural waterways, lakes and wetlands and many new types of ground water recharge systems that are tailored to the needs of urban trees. This approach is still not mainstream practice and is often funded through special grants.

Management of these new landscape systems is a challenge for many local councils who are geared to the old ways of maintaining parks and street trees. Landscape architects, WSUD engineers and those in local government responsible for streets and open spaces are now lobbying higher levels of government to fund and ensure this philosophy is implemented universally.

Conclusion

Planning for the greening of cities is important because trees and landscapes take time, often decades, to develop their full potential.

This planning needs to consider ways of providing the necessary water, drainage, oxygen and space, if soils are to be able to support increased vegetation in our cities as they evolve during this century. Of course planning needs to be supported with funds and management by all levels of government and the private sector as they maintain, renew and expand our cities.

The 202020 Vision developed for Australian cities has been an effective wake-up call that has helped create a case for serious funding and some networks and tools to put the wheels in motion.

2020 is two years away and we are only just getting started towards achieving the Vision. This will be a challenge that will continue way beyond 2020 and it will involve much more effort, money and coordination by governments, academia, the design professions and the private sector if our cities and towns are going to maintain, or even enhance, their sustainability and liveability under the pressures of growth and climate change over the next 20 to 40 years.

ALL GRAPHICS IN THIS ARTICLE ARE REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM 2020VISION AND THE CITY OF MELBOURNE WEBSITES IN THE INTEREST OF PROMOTING THE BENEFITS OF GREENER CITIES.

Comments (0)